PRBO CONSERVATION SCIENCE

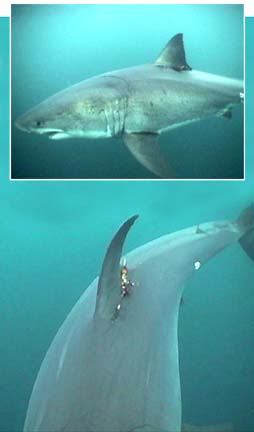

A satellite tag placed on the dorsal fin of this great white shark at a wildlife refuge off California can track its movements. At least one such shark has been traced to Hawaii waters.

Isles lure tourists

with teethScientists say a small group

of great whites qualify

as regular visitorsScientists say that a small population of great white sharks may be making regular seasonal visits to Hawaii waters from off California.

They suspect a tagged male dubbed "Tipfin" may have been the shark that bit a Manoa man on June 24, likely only the third great white attack in Hawaii in the past century.

"It stands to reason that if one's coming out, others are coming out," said marine biologist John Naughton, of the National Marine Fisheries Service in Hawaii.

Scientists are unsure how many great whites may be visiting Hawaii, but Naughton is working with California researchers at the Point Reyes Bird Observatory, who plan to tag 20 more sharks to learn the migration pattern of this little-known species. Naughton is gathering information from Hawaii fishermen, surfers, divers and boaters and has received more than 50 calls since the attack.

If you spot one...

>> Anyone who sees a great white shark is asked to call the National Marine Fisheries Service at 973-2935, ext. 211, or the state Shark Task Force at 587-0100.>> For more information on the Point Reyes Bird Observatory, visit www.prbo.org.

Tipfin, so named because of a missing fin tip, is the only great white tracked on the five-week journey from the Farallon Islands off the San Francisco coast to Hawaii for two years in a row.

"He should be in the Hawaiian waters now and -- who knows? -- he may be the one that bit the guy," Naughton said.

Great whites are thought to be in Hawaii waters from February through August, based on the tagging results and sightings, he said.

Fred Cohen, a snorkeler who witnessed the June 24 attack of John Marrack off Makua Beach in Waianae, estimated the shark at 14 feet long and 3 to 5 feet wide. Tipfin is about 15 feet long.

"We have strong evidence it's a white shark," said Naughton, though he cannot confirm the attack from secondhand observations of the description and behavior of the animal or the flesh wounds.

Marrack was bitten on the foot.

Tipfin was last tracked leaving California Dec. 9, 2001, and recorded in Hawaii Jan. 12, 2002. He spent the previous winter and spring here and returned to the Farallons in November 2001.

While traveling he swam at two consistent depths -- within 15 feet of the surface and between 1,000 and 1,500 feet.

Because of the $5,000 price per tag, few white sharks have been tagged at the Farallons, where they congregate to feed on young sea lions and elephant seals in the fall. Researchers attach tags into a shark's skin using a long pole as it passes by their small boat -- safe for shark and researcher.

"It's a common myth that sharks will jump out and attack humans, but the sharks are very focused on their next meal," said Sue Abbott, a biologist in the Farallons. "They're not the man-eaters that we are all familiar with."

The tags, which store data, pop off at a preset date and surface. The data is then transmitted to satellites and retrieved. Tipfin is no longer tagged.

Great whites, generally found in temperate waters, are uncommon in tropical waters, where tigers dominate.

"They've been here and the Hawaiians knew about them," said Naughton, noting great white shark teeth on some implements at the Bishop Museum. But he emphasizes "they're very rare in Hawaii."

In addition to last month's suspected great white attack, there are only two documented attacks in recent Hawaii history, Naughton said.

On May 18, 1926, William Goines disappeared off Haleiwa. His remains were found a couple of days later inside a 12-foot great white caught off Kahuku.

Licius Lee was bitten March 9, 1969, by a shark while surfing at Makaha, where a whale carcass was found. The great white was identified by tooth marks in the surfboard. Lee survived leg injuries.

Tipfin's recorded travels also give added credence to reliable sightings.

On June 9, 2001, free-diver Mike Garris came face to face with a great white while spear-fishing off Yokohama Beach Park but was not attacked.

The most spectacular account witnessed by beachgoers and lifeguards at Waimea Bay was of a shark leaping out of the water as it attacked a dolphin, something tiger sharks do not do.

Great whites have been spotted off Kaneohe, as well as Niihau and the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, where monk seals concentrate. Hawaiian monk seals are likely prey, but since they are so few, spinner dolphins are the next most likely prey, Naughton said.

Researchers theorize that since pregnant female sharks have been seen off Japan and Australia but not in California, they may be migrating from California to the western Pacific to give birth, making stops in Hawaii.

Males return yearly to the Farallons, while females return every other year.

After Naughton recounted the June 24 attack, PRBO researchers concurred that Marrack's description of a 5-foot-wide shark, silvery white in color with a large head, was consistent with a great white.

"I think what he saw was the underside of the head," Naughton said. Naughton estimates the shark weighed 2 tons.

Marrack was watching a pod of spinner dolphins about 30 to 40 feet below him and to the side, when another group of dolphins "went shooting along the surface like bullets."

Cohen's description of a clear demarcation line between the very white underbelly and a gray top with a black dorsal fin, black eyes and large gill slits matches that of a great white.

He first saw a dolphin pull away from the pod and watched as the shark, which he first thought was a larger dolphin, swam past.

"I saw the shark jump and hit the guy," said Cohen, who lives in the San Francisco Bay area.

That behavior fits great whites, which "have a habit of coming up underneath their prey very rapidly and leaping out of the water," Naughton said.

Abbott noted, "We believe their objective is to break the spine or snap the head off its prey and immobilize their prey."

However, white sharks rarely attack humans, she said. A shark may mistake the silhouette of a human as prey, "which is why it doesn't eat its victim because it's not a marine mammal; it's a bony human," she said.

Marrack, who is recovering, said there does not appear to be any ligament or tendon damage. His entire foot was in the shark's mouth, but it did not bite down hard, he said. "He could have crushed the whole foot," he said.

Great whites grow up to 20 feet in length and 5,000 pounds. Because they do not breed until age 15, researchers suspect they may live from 50 to 100 years.

Abbott said the great white, at the top of the food chain, is important in maintaining a balanced ecosystem, keeping the California marine mammal population in check.

"They play an important role in our fisheries," she said, since the marine mammals "eat what we like to eat" and compete with our fisheries.