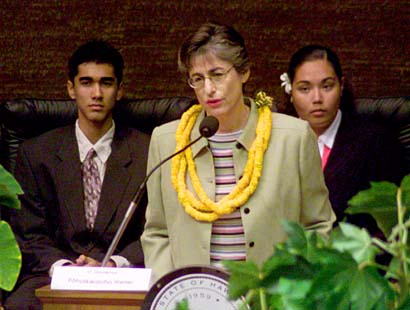

CRAIG T. KOJIMA / CKOJIMA@STARBULLETIN.COM

Gov. Linda Lingle spoke yesterday at the opening of the 16th annual 'Aha 'Opio o OHA, a summer leadership program for Hawaiian students. Behind her were master of ceremonies Hololapakanaenaokona Ho'opai and youth lieutenant governor Pohaikealoha Weller.

Bomb liability clouds

Kahoolawe transfer

Negotiating a transfer of Kahoolawe to the state from the Navy this year will be a major challenge, says Gov. Linda Lingle.

The challenge comes from unresolved liability issues surrounding unexploded ordnance on the former Target Island, Lingle said yesterday at the state Capitol.

An estimated two-thirds of Kahoolawe's surface is expected to be cleared of unexploded ordnance by November, when the state is to take control of the island.

"It's my belief that people on both sides have good intentions and are committed toward making certain that this happens in a way that is acceptable to all, but it will not be easy," Lingle told an audience of about 50 teenagers participating in the Office of Hawaiian Affairs annual youth legislature.

"The state not only has an obligation to the native Hawaiian community as it relates to Kahoolawe, but we have a responsibility to the entire community as it relates to any future liability that occurs because of the unexploded ordnance," she said.

The Navy will end its 10-year, $400 million-plus cleanup of the island in November. Under a 1993 agreement with the federal government, the state regains control on Nov. 11.

The state, via the Kahoolawe Island Reserve Commission, will hold the island in trust until a recognized native Hawaiian government is established. The island then would be turned over to that sovereign government, and the commission would dissolve.

In February the Navy estimated it could clear 69 percent of the island's surface and less than 10 percent of unexploded ordnance from its subsurface by November.

The island, which is six miles southwest of Maui, is comprised of 28,788 acres. Between 1941 and 1990 the federal government used it as a military range, but protests in the 1970s and 1980s forced the Navy to stop using the island.

Meanwhile, lobbying continues on a bill that sets up a process for a recognized native Hawaiian government that could eventually claim Kahoolawe.

Lingle told the OHA-sponsored 'Aha 'Opio Youth Legislature that federal recognition for native Hawaiians remains a top commitment for her administration. The problem, she said, is that many people in Washington, D.C., are unaware of Hawaiian culture and how it makes this state different.

"We're unique and we're special, and our country, America, has obligations to the native Hawaiian community and eventually to the native Hawaiian nation," Lingle said.

Micah Kane, chairman of the Hawaiian Homes Commission, was in Washington last week to continue lobbying for the so-called Akaka bill, which would set up a process in which Hawaiians can form their own government that could be certified by the U.S. secretary of the interior.

Kane, who testified earlier this year before the U.S. Senate on the Akaka bill, met with staff and leadership in the U.S. Interior, Housing and Agriculture departments.

Lingle is expected to meet with Hawaii's congressional delegation here on July 2 to discuss the bill, which is pending in the Senate.