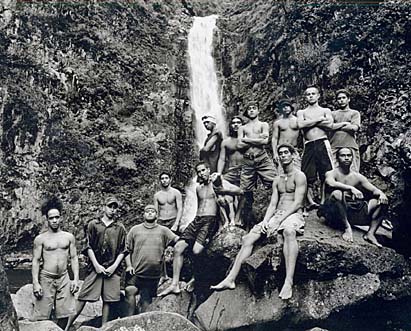

Monte Costa's black-and-white photographs chronicle the program called the Journey/ Molokai for troubled young men. Above, participants pose at Moaula Falls on Molokai.

Boys on

the brinkOutdoor adventure

teaches valuable lessons

The Hawaiians of old had a saying, "Ike aku, 'ike mai, kokua aku kokua mai; pela iho la ka nohana 'ohana."

The Hawaiian scholar Mary Kawena Pukui translated these words to mean, "Recognize others, be recognized, help others, be helped; such is a family relationship."

'Homestay Halawa: Boys on the Brink'

An exhibit of photos by Monte Costa:

On view: 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. weekdays through next Monday

Place: Honolulu Community College, Native Hawaiian Center, Building 7, Room 433

Admission: Free

These words come to mind when viewing a photo of young men standing proud before a waterfall in Halawa Valley on the island of Molokai. Their eyes hold a look of defiance.

Although the youths are unrelated, Monte Costa's collection of stark, black-and-white photos from Halawa convey a sense of family. The images, taken four years ago, are on view at Honolulu Community College's Native Hawaiian Center. The exhibit -- "Homestay Halawa: Boys on the Brink" -- inaugurates the school's new Artist in Residence Program.

The young men were subjects of a one-time program called the Journey/Molokai, sponsored by the Boys and Girls Club of Hawaii and hosted by the Glenn Davis family, of Halawa, Molokai. Glenn, wife Mahealani and their children Jeff, Aaron, Landon and Mana opened their home and land to 10 young men from Nanakuli and Waianae high schools who had run into trouble.

About four years ago, they were given the opportunity to learn in an alternative learning environment rooted in their Hawaiian culture and heritage.

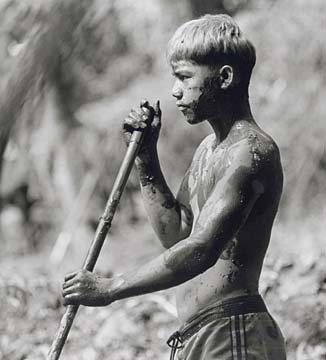

A hard day's work in a loi kalo, or taro field, is reflected in the boys' hands.

"At that time there was a ruling that if the kids were having a hard time in school, the counselors and principals could tell them, 'Don't come to school anymore,'" said David Nakada, executive director of the Boys and Girls Club of Hawaii. However, the schools' principals wanted the students to have a second chance.

Counselors and principals chose the students who were about to be let go from the schools to participate in the Journey/Molokai, according to Nakada. One requirement was that the parents of the young men had to take active roles in the application and orientation process.

"If the kids really wanted to do this, their parents would have to show up at the meetings," Davis said.

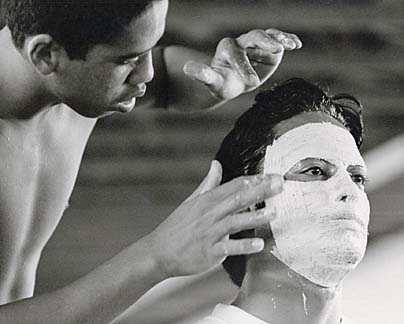

The retreat began with a secluded, five-day introspective process known as the Journey, held at Camp Waianae. A facilitator guided the young men to "discover" their coping skills by creating white masks as an aide to facing facts and fears about themselves.

The five-day experience was designed to have the teenagers "bond and break down the negativity around them, to have them see themselves as more positive," Nakada said.

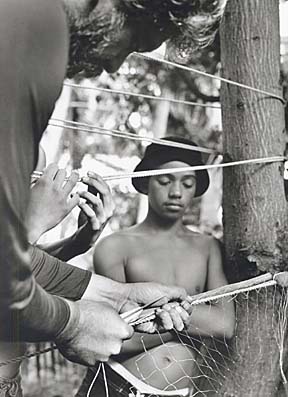

THE JOURNEY continued into Molokai's isolated Halawa Valley, where the teenagers learned about fence building, taro farming and ocean fishing from the Davis family.

The teens learn to work with throw nets.

"Most of these kids never fished, and a lot of them never worked in a taro patch," Nakada said. "A lot of it was hard work, but they always would come back and talk about what they did."

The boys had to carry their own drinking water into the valley, and in the process learned the importance of water.

Journal writing was also required, but it was a complicated assignment for the teens. "A lot of these young men had no writing skills, and so they didn't know how to write their journals," Nakada said. One of the kids had to take dictation from another who didn't know his alphabets.

The Davis' teaching strategies involved applying traditional classroom education to taro farming and fishing. Mahealani Davis added talks about Hawaiian culture and the history of Halawa Valley, while gently encouraging the boys to finish high school. "We would try to get them on a path to be successful and productive human beings," she said.

Although the Davis family is firmly rooted in the farming and fishing traditions, they sent two daughters to college in Washington, and a son is now studying at Maui Community College. Mahealani also went back to school and received her bachelor's degree in political science.

"That kind of stunned these young men," Nakada said. "The Davis family were great role models to the kids."

Davis said he emphasized the message, "If you are going to take steps in your life, education is one of the keys."

Douglas Kahala, above, throws a fishing net at Halawa Bay on Molokai.

After completing the program, participants returned to their Leeward Oahu homes. Nakada said that tracking the participants has been difficult because "they started to move in different directions. Some of the testimonies we got from the kids was pretty interesting, and a lot of them made some good choices."

In the program brochure, former participant Douglas Kahala said that prior to his participation in the Journey/ Molokai, he was "really dying. Being the eldest and not knowing what to do. Didn't have a father to tell me when you're an older brother you need to focus on this and this. It was all me to figure it out for myself. So, Uncle Glenn and Jeff them gave me that kinda knowledge and support that I needed to guide me."

Kahala received his high school diploma this year, joined the U.S. Army and got married.

Douglas Kahala builds a mask on the face of a fellow participant in a program called the Journey/Molokai. The exercise -- held at an orientation session at Camp Waianae on Oahu -- was meant to help the boys face fears about themselves. After graduating from the program for troubled youths, Kahala earned his high school diploma, got married and joined the Army. He now serves with the U.S. armed forces in Kuwait. Monte Costa's images from Molokai are on display at Honolulu Community College.

Even though some of the teenagers did improve, Nakada said he worried that the program failed because most of the participants were not equipped to document their experience. However, he said, "In the long run something like this would be a grounding mechanism for the rest of their lives, and if we could do that, it would be great."

Unfortunately, Davis became ill after the program ended, which left the family -- so instrumental in the success of the program -- unable to continue.

Yet Costa's photographs captured one family's attempt to share spiritual and cultural resources with disadvantaged youths for the benefit of the larger clan.

The Journey/ Molokai was held on land owned by the Glenn Davis family of Halawa, Molokai. The youths learned about fence building, taro farming and ocean fishing from the Davis family.

Click for online

calendars and events.