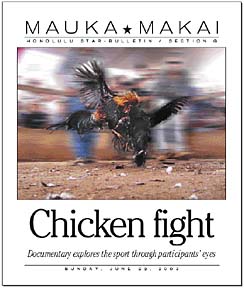

[ MAUKA MAKAI ]

SERGIO GOES

This photograph was taken by Sergio Goes, director of the Cinema Paradise Film Festival, which will be premiering Stephanie Castillo's documentary on cockfighting in September.

Capturing the Truth

A documentary captures views

from the widely condemned

world of cockfighting

Stephanie Castillo knew there had to be more to cockfighting than the dark images of criminal activity and cruelty to chickens that routinely appear in the mass media. Her beloved grandfather had bred and trained fighting cocks for 50 years -- surely he wasn't a depraved criminal!

Castillo, a former Star-Bulletin reporter and now an award-winning filmmaker, wasn't sure what she'd find when she set out in search of modern game fowl enthusiasts, but she was determined to capture the truth of the sport. Plans to create a feature-length film documenting the history and culture of cockfighting in Hawaii fell through when most of the local chicken people she contacted said, "Thanks, but no thanks," to going on camera to talk about the sport they love. Castillo understood their reticence.

It's legal to own chickens in Hawaii, but bringing chickens together to fight is not. Animal rights activists have targeted cockfighting for extermination nationwide, and most of the local gamers Castillo contacted didn't want to become targets of the crusade.

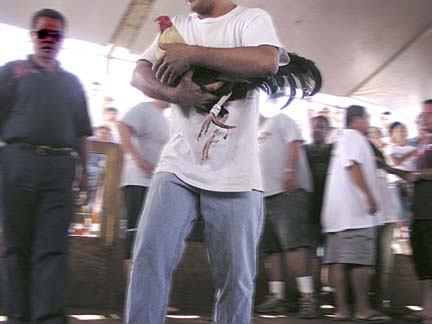

COURTESY OF STEPHANIE CASTILLO

It takes two years to raise a fighting cock. Successful breeders maintain studbooks that trace the lineage of their birds back generations.

"I found some people who were willing to talk because they've been in front of the Legislature asking that it be legalized, but in general it was very difficult. People were very closed, suspicious," Castillo said, as she explained how her plans for a conventional documentary film about cockfighting in Hawaii evolved into an eight-hour documentary entitled "Cockfighters: The Interviews." It's available for purchase on DVD, with a VHS release slated for a later date.

She interviewed 26 game fowl breeders and enthusiasts from 10 states and delivers a short history and overview of the sport's scope.

A 115-minute "Special Edition" VHS tape was made available for review as background for this story and will be made available on the film festival circuit. The work offers a fascinating look at a subculture Castillo says she didn't expect to find.

"It was totally a surprise to me. I only knew the dark stereotypes and the point of view of the animal rights people and the Humane Society. Going out there, I didn't know what I would find, and what you find and what you see on there is exactly what I got. It's not my point of view.

"I went to the people who were willing to talk with me, and I had two questions on my mind: What really is cockfighting? And, what is it about it that engages you in this sport? I had no agenda except to ask those questions, no point of view that I was looking for to justify or prove. No judgments, just questions," she said.

Castillo insists that "Cockfighters: The Interviews" and its shorter spinoffs are not intended to provide the game fowl industry with ammunition in its last-ditch struggle for survival, and puts the project in an anthropological context as a "document" of an obscure culture that may soon become extinct. Even so, the people who are seen in the special edition provide compelling arguments in support of the American game fowl culture:

>> The roosters are not brutalized or "forced" to fight. Fights between roosters occur naturally in the process of establishing a "pecking order," and cockfighters are merely allowing the birds to do what they would do anyway if given the chance.

>> Fighting is a minor part of the sport, albeit an important one. It takes two years to raise a fighting cock, and caring for game fowl is a day-in, day-out responsibility. Successful breeders maintain studbooks that trace the lineage of their birds many generations, and the primary purpose of fighting them is to prove the breeder's success in elevating bloodline quality.

>> Unlike the uncounted millions of factory-farm chickens that are raised in cramped and crowded pens before being slaughtered for human consumption, gamecocks are raised in fresh air and sunshine and are given plenty of room to move around. While factory-farmed chickens are doomed to a miserable life and a horrible death, a gamecock has a 50 percent chance of survival -- and those that prove themselves winners in the pit are retired to spend the rest of their lives at stud.

>> Gamecock breeders in the United States spend millions of dollars annually on chicken food and related supplies, pay to ship birds to other breeders or places where cockfighting is legal, and pay for travel to cockfighting tournaments, or "derbies," adding to the economy. (A spokesperson for the Hawaii game fowl industry recently guessed that Hawaii game fowl breeders pump more than $9 million a year -- all of it legal and subject to state excise taxes -- into the local economy.)

>> People who stigmatize cockfighting and want to eliminate the game fowl culture generally know little about it and are seeking to impose their cultural values on others.

>> Cockfighting has been part of American culture since colonial times and is popular is many other parts of the world. Abraham Lincoln got the nickname "Honest Abe" not for his politics, but because of his honesty as a cockfight referee.

"I may have just documented something that's going to be gone. ... Maybe that's all I did was leave a document -- What are you guys about? Why do you do this? -- and that's what I'm showing. The short film is a little more complicated because I wanted to capture their feelings ... so it may look like I'm promoting (cockfighting) or endorsing it or whatever. I was truly just trying to capture the emotions that I felt from them about their sport and how they viewed it."

NONE OF THIS is likely to make "Cockfighters: The Interviews" sit well with animal rights activists who have found that a crusade against cockfighting is much more palatable to mainstream Americans than attacks on factory-farms and slaughterhouses. Most Americans prefer not to know about the conditions under which the factory-farmed chicken, pork and veal is produced for their consumption, while a ban on cockfighting has no impact on their diet or lifestyle.

COURTESY OF STEPHANIE CASTILLO

Cockfighters say fighting is a minor part of the sport and that the primary reason for fighting is to prove the breeder's success in elevating the quality of his bird's bloodline.

"Animal rights people have one mindset, and (cockfighters) have another. I grew up with slaughtering chickens; that's how my grandmother fixed dinner. ... I grew up seeing that, so I guess in a sense it's desensitizing, but that's the way people lived on farms and in rural places. Seeing two birds fight wasn't any more upsetting than seeing grandmother kill a chicken for dinner."

Castillo says game fowl enthusiasts nationwide and in several foreign countries are preparing to appeal a recently passed addendum to the Animal Welfare Act that makes it illegal to ship gamecocks anywhere for the purpose of fighting -- even to places like the Philippines or Mexico where the sport in legal. The Humane Society of the United States pushed for the amendment -- specifically to include the ban on exports to foreign nations -- with the purpose of shutting down the game fowl breeding business in Hawaii.

Castillo said she didn't intend her documentary to support one side of the issue or the other, but said: "If this allows (cockfighters) to speak up about what they do and help us understand so we pass better laws or more humane laws or laws that aren't so hysterical, then maybe the society here in Hawaii will be better for that, but I don't know. I'm just putting it out there."

OPPONENTS OF game fowl breeding, and those who feel that Castillo's interviewees -- two from Hawaii, six from the mainland -- are too persuasive in defending their culture and way of life, may note that she doesn't show much of the actual business of birds fighting. "If I did it, it would have to be surreptitiously and illegally. I didn't really see the point."

There's a brief scene in which two birds engage in a bloodless battle in the Philippines, and mention is made of fights that took hours to resolve, but there's little sense that testing the pedigrees of these beautiful birds results in many of them dying.

Even without footage of birds killing each other, "Cockfighting: The Interviews" could easily be one of the most non-PC American films since "L.I.E." portrayed a homosexual pedophile as an almost sympathetic anti-hero.

"(Cockfighters) aren't demons," Castillo says. "I thought I would meet all these seedy, greedy, weird (people) ... and one of the biggest surprises was how nice these people are. Maybe there are some demons out there, but I sure didn't meet them.

"We have tens of thousands of people here in Hawaii that do this sport or watch it. They're not demons, but we've made them out to be demons. Are they really?"

A condensed version of the work may eventually run on PBS, although nothing has been finalized. "I don't have a television broadcast intention at this point," Castillo said. She's hoping that interest in her DVD among cockfighters, university libraries, social science and American studies departments, and the general public will generate enough sales to allow her to pay off her production costs.

"A supporter of the arts gave me some money (to make a film), and after he gave me the money he asked what I was going to make it about. I could make it about anything I wanted to, and it was in that moment that I thought about my grandfather's livelihood of being a cockfighter and wanting to explore it," Castillo said.

"It opened this window to my own cultural background and family history, and by meeting these people and talking to them, I understand the minutiae of what must have involved my grandfather for 50 years. I would never have guessed it was all that complicated. It looks really simple ... but what was revealed to me in the study was just how complicated (it is). It is not black and white."

Castillo says she knows that many people prefer to view cockfighting in those terms and may attack her and "Cockfighters: The Interviews" for deviating from their viewpoint.

"Attacks will only question why people would not want more information out there for the public. I think the public will say that this woman is trying to give us some information so perhaps our laws will be much more informed and less reactionary ... and I think there will be people that will be happy to get this information. They may not support cockfighting or like it, but at least their opinions will be more informed, their decisions will be more informed, and I think we'll be able to respect them more than those who come at it from a very hysterical demonizing (perspective)."

"What I've found (about cockfighting) is that it is very hard to judge. It's not about wanting to see two birds kill each other. It's about wanting to see your bird survive."

"Cockfighters: The Interviews" is available on DVD for $140, with a VHS version to be released at a later date. To order, call 739-3938 or order online at http://members.aol.com/cfighters4sale/buy_DVD.htm.

Click for online

calendars and events.