Filipino men’s

cancer rates riseTumor registry data show a

dramatic increase most likely

linked to smoking

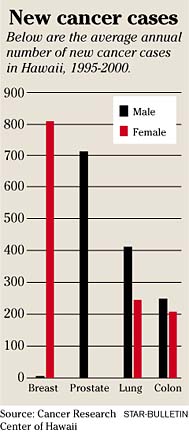

Filipino men have jumped from one of the lowest cancer rates in Hawaii to one of the highest, mainly because of lung cancer.

This was a significant finding in recent data gathered by the Hawaii Tumor Registry, established in 1960 to track and study all cancer cases in the state.

Marc Goodman, researcher at the registry, said cancer incidence rates for Filipino men in the past "have always been among the lowest overall."

But he said, "They just are not quitting smoking, which leads to all sorts of diseases."

He cited the case of Filipino men to illustrate the importance of information gathered by the Hawaii Tumor Registry, one of the oldest in the country.

It is part of a national Surveillance Epidemiology End Results (SEER) program, which conducts surveillance on new cancer cases and follows them until death.

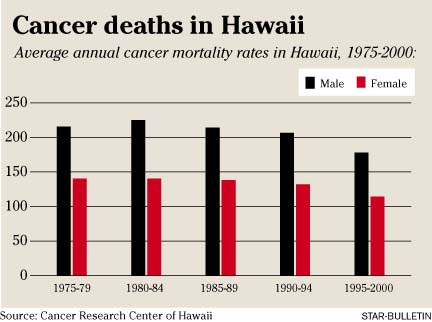

In this way, Goodman said, researchers can see how well prevention programs, screening and new therapies are working to decrease the number of cancer cases and mortality.

The goal is to reduce cancer deaths by 50 percent by the year 2015, he said.

Two major conferences here this month have focused attention on the tumor registry, operated by the Cancer Research Center of Hawaii.

The North American Association of Central Cancer Registries met last Tuesday to Thursday at the Ilikai Hotel with about 300 participants. The 25th Annual Scientific Congress and Meeting of the International Association of Cancer Registries will convene today through Wednesday at the Ilikai. About 175 delegates are expected.

Dr. Carl-Wilhelm Vogel, Cancer Research Center director, said the location of both conferences here reflects the Hawaii registry's "fine reputation among its peers." He said it "represents the forefront of national demographics because of our state's multiethnic population."

Goodman said most epidemiology research at the Cancer Research Center is based on data from the registry's surveillance system. Information from driver's license files is linked to the registry for the studies, he said.

The registry also is creating a repository for tissue from all cancer patients in the state, Goodman said.

"That will allow us to do incredible molecular work, from genetics, reaction to radiation, prognosis and all kinds of things."

For example, he said there has never been a study to show the prevalence of the breast cancer gene that puts women at high risk, or the distribution or frequency of the gene in various populations.

With the tissue bank, he said, "We'll be able to look at the new gene and diagnostic tools and prognostic markers on a population basis, and we'll be able to do it quickly."

Goodman said the Hawaii Tissue Registry "is the only registry probably in the world, but I know in the United States, that has this kind of tissue repository."

Several specialists will join the program to assist with the tissue bank and molecular analyses.

A similar repository is being developed with fresh tissue from consenting patients going into surgery, and noncancerous tissue is being saved as well as diseased tissue for comparisons, Goodman said.

Linking tissue analyses with data from the tumor registry and research programs "offers tremendous potential for us" in understanding cancer, Goodman said.

He said the registry just received a $10 million award from the National Cancer Institute for seven years.