HAWAII UNDERSEA RESEARCH LABORATORY

Christopher Kelley, chief biologist for the Hawaii Undersea Research Laboratory submersible Pisces V, records data aboard the vessel near Kahoolawe.

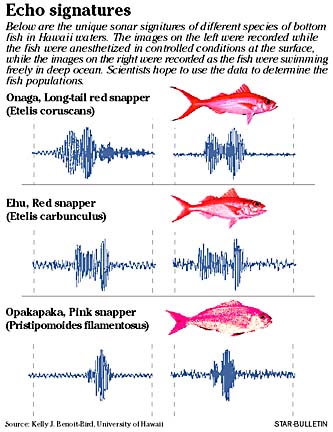

Scientists use sonar

to help identify

favorite isle fishThey hope to tally ehu, opakapaka and

onaga populations by using echo traits

Scientists are experimenting with sonar to help them determine the populations of some of Hawaii's favorite fish, like ehu, onaga and opakapaka.

All three are deep-sea bottom fish, and two of them, ehu (red snapper) and onaga (long-tailed red snapper), are endangered. opakapaka (pink snapper) is close to being labeled as endangered. Working with the Hawaii Undersea Research Laboratory submersible Pisces V, the scientists measured echo characteristics of various species in waters off Kahoolawe.

"We're trying to find out if we can use sonar to identify bottom fish so we can nonlethally survey them," said Kelly Benoit-Bird, with the University of Hawaii Department of Zoology, Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology.

"If we go in there with fishing gear to try and figure out what's going on, it's counterproductive," said Chris Kelley, HURL chief biologist and HIMB researcher.

One possible method of assessing the fishery without killing the fish is with acoustics, he said. "Let sonar be your eyes, and you're hoping to get sonar information that's detailed, with high enough resolution that you could actually distinguish different species."

Others working on the project are Whitlow Au, chief scientist for the HIMB Marine Mammal Research Program, and Christopher Taylor, engineer-manager of HURL's remotely operated vehicle (ROV).

Benoit-Bird and Au have been studying the acoustic signature of bottom fish, while Kelley has led a program to collect information on Hawaii bottom-fish populations and habitats.

Bottom fish have an air-filled swim bladder that creates an echo, but the amount of air compresses as the fish go deeper, Benoit-Bird said.

"We weren't sure if under pressure the size of the bladder would change and, if it did change, if it would make all the results at the surface difficult to interpret."

Using sonar on the submersible with video and low-light cameras for observations, they found the fish were able to regulate the size and shape of their swim bladders even under huge pressure as they went deeper, she said.

Swim bladders have complicated shapes that are different for each species, and the shape ultimately will be the key to telling the fish apart with sonar, she said.

Kelley said the submersible work will help to find more cost-effective methods of surveying the fish, such as sonar with video and low-light cameras.

The National Marine Fisheries Service is building a drop camera mounted on a platform that can be put on the side of a small boat, he said.

"We have a low-light camera that works really well," he said, explaining fish will avoid artificial light. The camera takes available light in the deep water and amplifies it and enhances the image, he said.

The fish were drawn to the submersible with bait, then video-taped, he said. A sonar transducer attached underneath the camera bounced sonar pulses off the fish. "They got really, really good acoustic information from different species," Kelley said.

"They could see with the camera exactly what species created the echo, how oriented it was to the sub and how large the fish was."

The scientists' findings were reported in ScienceDirect, an information source for scientists worldwide. The article, "Acoustic backscattering by deep-water fish measured in situ (their natural habitat) from a manned submersible," was the first published account of use of a manned submersible to measure fish in their habitat.

Benoit-Bird said the next step is to measure echoes of live fish swimming in a pen to observe the effects of movements of different fish, groups and mixed species and see if they can tell the difference.

Kelley, who has been studying bottom-fish populations to help the state Department of Land & Natural Resources improve management of the reserves, said he is about to start another three-year phase of research under a new grant.

Kelley said Au is going to experiment with two methods of monitoring the fish in their natural habitat.

One is to build a torpedolike device with sonar that can be lowered or towed behind a boat and above the fish looking down, he said.

The other way is to place a mooring at an important fish-aggregating site with a sonar system that looks up at the fish, he said.

It could be left there six months to a year to collect data on the numbers and types of fish going into the area over time.

In the submersible dive this year, Kelley said, they will try to orient the sonar and cameras vertically in the water to get signals overhead and underneath the fish.