[ MAUKA MAKAI ]

RICHARD WALKER / RWALKER@STARBULLETIN.COM

At Waiau District Park, Takao Fujitani keeps a stern eye on the youngsters as they work on their judo moves.

Takao Fujitani and his offspring

have made judo a family affair

There were few girls taking judo classes when Karin Fujitani was 12, but rather than feeling awkward about her lessons, she looked forward to flipping the boys. "When I threw a guy, it was pretty cool," she said.

Karin started her training with her father, Takao Fujitani. "It was a good outlet," she said.

"My daughter wanted to start classes earlier, but I made her wait until her brothers were older, so all three of them could start together," said Fujitani. His sons, Dwayne and Neil were 10 and 8 at the time.

At first, Karin and her two brothers simply hung around at the practice site. "We would make fun of (the students) as they called out the (moves)," said Dwayne.

Times had changed since Fujitani was a child. During World War II, Japanese cultural practices were forbidden to avoid the appearance of siding with an enemy nation. "We couldn't speak the language or do anything that was Japanese," he said, until he was a teen. And then, once he was exposed to the martial art, he was hooked.

Sharing his knowledge with the next generation was also instilled in him. "My teacher told me that I must keep teaching. If you stop, no one continues on," said Fujitani. He became a sensei in 1952 and now is a Shichi Dan (seventh-degree) judo instructor.

"My father retired early from sheet metal so he could teach," said Dwayne.

RICHARD WALKER / RWALKER@STARBULLETIN.COM

Rushing to learn judo can result in injuries, says Takao Fujitani, as he closely monitors his students' drills of basic techniques. Learning to fall is essential and lessons in mastering te fall can take up half the class.

In addition to teaching his own three children, he's taught hundreds of kids at various locations on Oahu.

One Saturday morning, a man watched his entire class with interest, approaching the sensei at the end, asking, "Are you still teaching?"

"He said his daughter used to take my class when she was little, and now she's 46."

SENSEI CONTINUES to teach at Waiau District Park, Halawa Gym, Moanalua High School and at all the Boys and Girls Clubs. When asked how he keeps up, he just says he has to "make time."

Judo is a slow process, said Fujitani. For that reason, it has not caught on as quickly as karate. But, much like Mr. Miyagi's teaching how motions used in waxing a car can be translated into martial arts movements in the film "The Karate Kid," Fujitani shows the children how simple and seemingly useless movements can be powerful when everything is put together. At some classes he even takes out a broom to demonstrate the correct way to "sweep the feet."

Dwayne is a black belt and now helps his dad as an assistant sensei at the Waiau Judo Club. Blue and white mats fill the recreation center where dozens of kids gather for lessons every Wednesday and Saturday.

"I help my Dad every Wednesday and then go and eat dinner with my parents," said Dwayne.

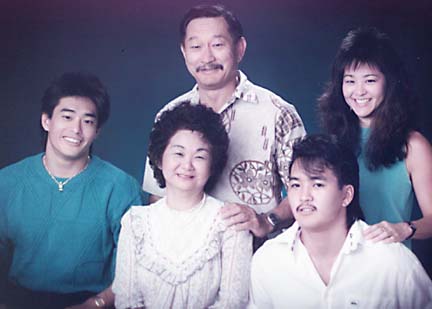

COURTESY OF FUJITANI FAMILY

The Fujitani kids say their father was tough on the judo mat but, "it didn't matter if we did good or bad at class. He left everything at the dojo." This family portrait was taken in the '80s.

Fujitani is protective of all the kids in class. "The most important thing: Make sure they are safe and sound. I don't want them to get hurt," he said. "If they are taught correctly, they won't get injured."

Lots of injuries occur at the high school level, where broken collarbones and dislocated elbows are common, he said. He attributes the problem to rushing to learn too fast without mastering basic techniques first.

Fujitani's youngest son Neil, a black belt, is now a judo coach at Iolani School. "I was youngest when we started. There was always big expectations for us because we were Fujitani's kids," he said, adding that he was grateful that his father kept their family life separate. "It didn't matter if we did good or bad at class. He left everything at the dojo."

The biggest lesson Neil learned through judo was how to create balance in his life. "My parents showed me that -- the tough and the mellow," he said.

THE KIDS TOW the line in class. Once they laugh or start playing around, a stern glance usually stills them. If not, Fujitani pulls them off to the side and makes sure they understand they are to be serious while training.

"He used to scare us and he never touched us," said Dwayne.

"He is an old Japanese samurai. Affection was not a part of the picture. I think he hugged me once, at my graduation," he chuckled.

Although physical affection was not part of the deal, Fujitani taught his children the importance of giving. Most of the classes he teaches are on a voluntary-fee basis.

"I could not fathom that at first," said Dwayne. "It's his full-time job but he doesn't get paid."

"Teaching judo is my father's passion -- it's not for the money," Karin added.

Now a volunteer sensei himself, Dwayne can relate to his father's philosophy. "Giving back feels good," he said, while hoping that the children appreciate -- if not now, then later -- his attempt to make a difference in their lives.

Neil also finds teaching fulfilling. "It puts you in a good position to help people."

DISCIPLINE was an important factor in the Fujitani clan's upbringing. "We were brought up with the understanding that once you start things, you must finish them," said Karin, who is now thankful that her mom sent them off to judo classes, even on those days they preferred to play outside.

But don't get the impression that the children were forced into their lessons. "We went because most of our good friends were there," Dwayne said. "But I didn't like it after a while because I wasn't so good. My sister used to beat me up."

"She used to beat everyone up," he added.

Karin now has a 3-year-old son who is eager to follow in his grandfather's footsteps.

"I think I would have been in a lot more trouble if I hadn't taken judo," said Dwayne. "A lot of my friends would have probably been in jail if it wasn't for judo. Goals are set for you," he explained.

Neil agreed. "We had to be at practice, so we couldn't goof off. If kids are in sports, it helps keep them off the streets."

Self-defense is yet another reason to invest time in martial arts.

Karin recalled an incident that occurred at Ala Moana Center when she was a teen. "I was shopping with a friend, and a gang of girls approached us," she said.

They wanted money, and when Karin told them no, "they started circling me and threatening to beat up my friend."

Eventually, they grabbed Karin's coin purse, and she snatched it back. After some scuffling the gang backed down.

"Judo would not be my first option to deal with the situation," she said, adding that having confidence in one's ability to defend oneself can be intimidating.

Fujitani believes that judo was a contributing factor in the situation's outcome. "They knew she was not afraid," he said.

Click for online

calendars and events.