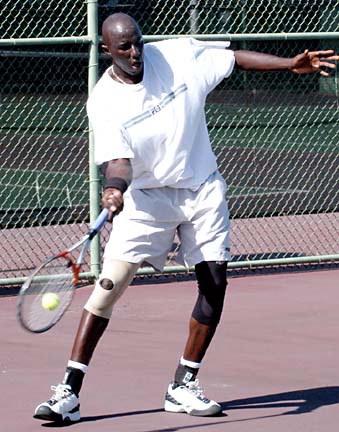

PHOTO COURTESY BYUH ATHLETICS

Brigham Young-Hawaii senior Daouda Ndiaye has won six matches for Senegal in the Davis Cup -- four of them in doubles.

Don’t doubt Daouda

The Brigham Young-Hawaii senior

wins for his team when it matters most

Tennis is a rich man's game, full of the types of people who leave old tennis balls scattered around a court after practice because they believe that they have squeezed every bit of usefulness out of them.

Then someone will come along and squeeze more out of it than they ever thought possible.

Daouda Ndiaye is Brigham Young-Hawaii's Mr. May, squeezing enough out of his skills to win when it really counts.

As the fifth player on the top-ranked team in the nation, Ndiaye's points are rarely needed. The 25-1 Seasiders have shut out their opponents 17 times in 26 matches this year, making each match a race to see which Seasider can finish off his opponent first and earn a point for his team before the matches are mercifully ended.

But whenever May rolls around, Ndiaye quite possibly becomes BYUH's most valuable player.

Ndiaye won two crucial matches for the Seasiders at the national tournament last year, including when he rallied to beat Drury's Akos Tajta in the final match to give BYUH a 5-4 victory and the NCAA Division II title. Ndiaye beat Stephan Pampulov of Hawaii Pacific earlier in the tournament to give BYUH another slim 5-4 win.

Ndiaye has never lost a singles match at the national tournament, which began today with a regional at Laie. The Seasiders are expected to steamroll their regional opponents like they have everyone else; but if the stars align and a lesser seed can make it close, they are going to have to go through Ndiaye.

And that is just the way BYUH coach Dave Porter likes it. He has recruited such a strong group that his fifth-best player took time off from his team in February to represent Senegal in the Davis Cup and has won six professional matches before graduating from BYUH last month. Most NCAA teams put a project in their fifth spot, a player who is learning as he goes, but Ndiaye has already been there.

The NCAA allows its tennis players to play professional tournaments or represent their country as long as they don't profit from it. Ndiaye says he would have turned professional already if a sponsor would have noticed his performance at last year's nationals, but none did and he returned to school to try to help the Seasiders repeat their national championship. He will attempt to capture the imagination of a tennis fan with pockets deep enough to make him a tennis star again this year.

"Turning pro, that's my dream, but I have no sponsor," Ndiaye said. "Unfortunately professional tennis is not a matter of talent as much as it is a matter of money. I know I would be able to win if I got the chance."

And it is the money that allows Ndiaye to either take the dream or leave it.

Just 20 matches into his pro career, he has already gotten more from the professional tennis circuit than he has given. The system has given him a fiancee, Imen Jouda, who hosted him at a tournament in Algeria in 2000 and will marry him in September.

"Lightning struck and we fell in love," said the Muslim who has fit in at the Mormon school. "There is no way she is not going to visit Hawaii, Hawaii is part of my life the same as she is. Hawaii changed me."

Ndiaye was not a poor child when he was growing up in the Congo, but he wasn't rich, either. His father, who was an ambassador and executive for the World Health Organization, had the money to get him -- and his eight siblings -- the best schooling available, but not enough to keep his boy from dreaming.

Long before he can remember -- his mother puts the time frame at around 5 years old -- Ndiaye has been captivated by the game of tennis. He lived within sight of a pair of clay courts in the Congo, but he was not allowed to step foot on them until he either became a diplomat or became white. Not being very interested in school, both had equally slim chances of happening.

So Ndiaye fashioned his own racquet out of wood -- no strings attached -- and played in the street in front of the forbidden courts, trading two hours of basketball with his friends for an hour of hitting. It didn't take long for his friends to tire of it though, and Ndiaye bravely stepped on the courts and asked a couple of men if he could shag balls for them. They accepted and rewarded him with a few minutes with their racquets. They ended up giving him so much more.

The men -- some of them diplomats and some of them white, and all colleagues of his father -- began calling Ndiaye's house asking if the 14-year old could come out and play. Ndiaye's father wasn't sure about it, but also was out of town on business a lot.

Ndiaye quickly -- and secretly -- got better and better until he signed up for a tournament in another part of the country. That decision effectively killed the secret.

Ndiaye showed up at the tournament with a borrowed racquet and beat Africa's top three players, capping it off with a championship televised around the nation. The men who gave him his start showed up to cheer him on in the final, and still follow his career as closely as teenage girls follow Andy Roddick's.

Ndiaye went home expecting the wrong end of a paddle. Instead he got the right end of a tennis racquet.

Ndiaye's father had never considered athletics as anything other than a distraction from education. He only allowed Ndiaye to continue with the game because his teachers said without tennis his boy was a "very unhappy child" and unlikely to succeed in school. He responded by giving the young man his first two real racquets.

They are gone now, as the family had to leave everything behind and flee the Congo for Senegal to escape war.

But the game remains in Ndiaye's heart. It has given him a college education and hope for the future, possibly a chance to one day return to the Congo or earn a living in his new paradise.

"Seventy percent of what I am today started in the Congo," Ndiaye said. "But it is not yet a safe place. To be able to go back and see the family I left behind would be so, so cool. But I will never forget Coach Porter and Hawaii. I hope God will keep my head straight so that I will not forget what Laie has done for me."

Ndiaye, who was sent to a boarding school in France at 17 because he was such a bad student, got his college degree last month with a 3.0 grade point average and is actively looking for a job in Hawaii should the long shot of professional sponsorship not happen. His degree is in communications, but his heart is still stuck on tennis. That's what happens when a racquet has been your carry-on luggage for as long as you can remember.

After the second national championship he is counting on earning, Ndiaye says that somehow, some way he will find a career that blends both tennis and communication -- possibly teaching youngsters to squeeze even more out of a tennis ball than he did.

BYUH Athletics