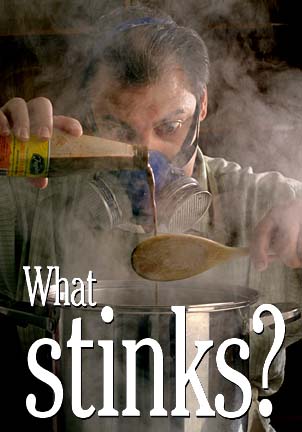

DEAN SENSUI / DSENSUI@STARBULLETIN.COM

"Mad Man" Dan Hermon protects himself with a respirator as he stirs a heaping helping of bagoong -- Filipino fish sauce -- into his steaming pot.

Fragrant fish and shrimp

sauces add pungent punch

to Asian cuisine

Fermentation is the breakdown of complex molecules in organic compounds. Sterile words for a process that leads to the most smelly, sour outcome.

Take, for example, a ton of anchovies, mackerel or shrimp. Add several pounds of salt and water to create a brine -- then let the mixture slowly stew and bubble for months. The resulting seething concoction may draw putrid jokes, foul criticism and utter disgust. But there is no arguing that it is a marvel of fermentation.

These stinky sauces are basic to the Asian pantry -- called bagoong or patis in the Philippines, nam pla in Thailand, nuoc mam in Vietnam, hom ha in China, saeu chot or myolchi chot in Korea and kusaya gravy or shottsuru in Japan. In English call them fermented fish or shrimp sauce, gravy or paste. Whatever the name, these basics to street food and regional home cooking have begun to intrigue the Western palate.

Like soy and chile sauces, Asian fish sauces have become the rage, despite their pungent notoriety, due in large part to the popularity of Thai and Vietnamese food.

The concept is familiar to some Europeans as well. Ancient Romans fermented anchovies in much the same manner as Asian fish sauces are made. The resulting condiment, called garum, was a flavoring agent. The popularity of salt-cured anchovies in Mediterranean cuisine today is a testament to garum's extensive historical use.

In Asia, fermented fish sauces date back hundreds of years and were initially a way of preserving a large catch. They were also an important source of essential protein and B vitamins in a diet consisting mainly of rice and vegetables.

Over the years, fish sauce became indispensable. Without it certain dishes would just not taste the same.

Asian cultures generally favor a more complex method of salting dishes as they cook. Like soy sauce, fish and shrimp sauces add dimensions of flavor and aroma to dishes that simply cannot be obtained by purely salting.

Fish sauces will generally keep for quite awhile without refrigeration, although they can be refrigerated. Shrimp sauces are more perishable and should be refrigerated after opening.

Fish sauces are very reasonably priced, at $1 to $3 a bottle, depending on size. Shrimp sauces are a bit more expensive, as are premium fish sauces regarded as extra virgin.

Keep in mind that a little goes a long way with these sauces. Only a tablespoon or two is necessary to flavor a whole dish.

A guide through the aromas:

Filipino bagoong: Made of ground or creamed fermented fish or shrimp. Bagoong alamang, sometimes called salted shrimp fry, and bagoong balayan, an unfiltered fish sauce, are two popular styles of the many varieties bottled.

Patis: Filtered juice or gravy derived from fermented fish, this Filipino sauce may be made from scad, herring, mackerel, sardines, anchovies or other small fish. It is amber-colored and similar in taste to Southeast Asian fish sauces, although more pungent and salty. Patis can be interchanged with bagoong in recipes, depending on personal preference.

Nam pla and nuoc mam: These are the most popular fish sauces because of their relatively mild flavor. Anchovies are the primary ingredient. Quality varies in the same way as with olive oil. In fact, the first pressing is referred to as extra virgin and is recommended as a dipping sauce (with a bit of sugar added to make it more appealing to the Western consumer). These sauces are the primary condiment in Thailand and Vietnam, used daily in everything from soups to salads.

Whole fish sauces: These include large chunks of fermented fish such as gourami or mudfish. Mashed with other seasonings, the sauce is used as a base for stews throughout Southeast Asia

Hom ha: The smell of this sauce, made from fermented, ground, tiny shrimp, is said to turn off even most Chinese chefs and is quite a challenge for the unaccustomed. The pinkish-gray paste is used in clay-pot casseroles, noodle dishes and the popular hom ha fried rice. A less perishable, dried form of shrimp paste is sold in bricks and used in Southeast Asian curries, marinades and sambals.

Korean and Japanese fish sauces: These lesser-known sauces aren't produced commercially outside of their respective countries and can be difficult to obtain. Korean fish sauce (labeled anchovy sauce) is sometimes sold next to kim chee pepper sauces. A key ingredient in kim chee, the fish sauce not only adds flavor but serves as an important fermenting agent for the cabbage. Japanese kusaya, or fermented mackerel, is a favorite grilled item. The whole fish, rather than just the brine, is the delicacy. Another Japanese fish, shottsuru, is popular in soup and hot-pot dishes.

The following are two very approachable recipes using fish sauce. The first is a classic dipping sauce that can be served with spring rolls. The second is a favorite Filipino vegetable stew.

Mix garlic, fish sauce, lime juice and sugar. Stir to dissolve sugar. Stir in chile oil. Serve in small bowls, for dipping with fried food. Serves 4 to 6.Vietnamese Dipping Sauce

"Asian Ingredients: A Guide to the Foodstuffs of China, Japan, Korea, Thailand and Vietnam," by Bruce Cost (HarperCollins Publishers, 2000)1/4 cup minced garlic

1/2 cup fish sauce

1/3 cup fresh lime juice

1 tablespoon sugar

1 teaspoon chile oilNote: This sauce is best made 1 hour ahead.

Nutritional information unavailable.

Layer ingredients in a shallow pan, preferably one that can be brought to the table. Add water almost to cover. Simmer, loosely covered, 20 to 25 minutes, or until vegetables are tender. Shake occasionally to ensure all the vegetables are evenly cooked, but do not stir. The dish should be almost solid, but not dry. Serve with rice. Serves 4 as a side dish.Pinacbet

"The Food of Paradise," by Rachel Laudan (University of Hawaii Press, 1996)

3 or 4 eggplants, preferably long Japanese type, cut in strips 1 inch long and 1/4 inch thick

1/2 pound okra, wiped, caps cut off

2 bittermelons, cut in strips 1 inch long and 1/4 inch thick

2 to 3 tomatoes, in segments

6 long beans or green beans, in 1-inch lengths

1 medium onion, halved and sliced

1-1/2 inch piece fresh ginger, peeled and crushed

1 tablespoon bagoong

Salt to tasteNote: Add 1/2 pound shredded pork to make this a meal.

Approximate nutritional information, per serving, without pork or added salt: 130 calories, 1 g total fat, no saturated fat, 5 mg cholesterol, 360 mg sodium, 28 g carbohydrate, 6 g protein.

Nutritional analyses by Joannie Dobbs, Ph.D., C.N.S. Eleanor Nakama-Mitsunaga is a free-lance food writer. Contact her at the Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 7 Waterfront Plaza, Suite 210, Honolulu 96813; or e-mail her at: features@starbulletin.com

Click for online

calendars and events.