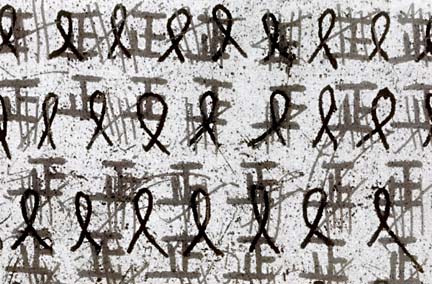

E. Chihye Hwang's "Sine" is among the artwork featured in "YOBO: Korean American Writing in Hawaii."

An anthology explores themes

of Korean identity in Hawaii"The Glass Wall" excerpt

CORRECTION

Friday, May 2, 2003» Victoria Sung Hye Chai Cintrón lives in a care home. A story on Page G7 in Mauka-Makai Sunday said incorrectly that she died.

The Honolulu Star-Bulletin strives to make its news report fair and accurate. If you have a question or comment about news coverage, call Editor Frank Bridgewater at 529-4791 or email him at corrections@starbulletin.com.

"The word yobo still brings that pinch of pain, conjuring up old injuries from the playground where bullies would taunt, 'Hey, Yobo! You stink-face, kimchee-eating yobo-jack!'

"Back then, yobo meant Keeaumoku Street hostesses ... who called out to men in the streets: 'You likee buy me drinkee?'

"Yobo meant Kitchen Mamas stooped over the grill at hole-in-the-wall Korean take-out joints, or vendors peddling gold-plated trinkets and psychedelic candles at Duke's Lane, or FOBs squatting in airport terminals with coolers of kimchee and bundles of bedding like refugees from a country we all wanted to forget.

"Yobo meant hardhearted, hot-blooded shame."

-- From the introduction to "YOBO: Korean American Writing in Hawaii"

Cultivated from a country fraught with invasion and division, the Korean cultural identity for those reared in America is disconcertingly fragmented.

"There's a strange visibility, on one hand," says Brenda Kwon, one of five editors of "YOBO: Korean American Writing in Hawaii." "There are the bar girls -- which, by the way, I don't necessarily see as a bad thing. I think we need to claim them as our own, not shun them. And on the other hand, there are the prominent personas like (University of Hawaii regent) Donald Kim, who is a very successful businessman.

"Such divergent images! I don't think we have an identity that encapsulates the different communities in Hawaii that are Korean.

"At the Korean centennial banquet, there were 1,500 of us there. It was shocking to see so many of us together. I knew of lot of people there, but there were many others I didn't know. We don't have a lot of unity now. We're still trying to figure each other out. We're still emerging."

Unity has been a struggle for the Korean people throughout the nation's history. Korea has been a strategic zone that has borne cultural, political and military clashes from China and Japan. Once western religion was introduced to Korea in the 17th century, contact and resulting conflicts began, with China, Japan and then Russia vying for dominance over the nation.

The First Sino-Japanese War (1894-95) and then the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05) gave Japan control of Korea. After World War II, when the Japanese surrendered to the Allies, Korea was to have been liberated. But the country was instead divided along the 38th parallel of latitude between the United States and the Soviet Union. That military demarcation line became the boundary between two Korean states co-existing in a state of shaky truce.

"5,000," by E. Chihye Hwang, 2002

GATHERING the works for "YOBO," a Bamboo Ridge Press anthology of historical essays, prose, poetry and art, was to illustrate the emergence and baby steps toward the unity that Kwon speaks of.

"We were really scared at first that we wouldn't be able to fill out a whole anthology," said Kwan, who co-edited the work with Sun Namkung, Gary Pak, Nora Okja Keller and Cathy Song. "We were going to the library to research Korean-American writers. Because in Hawaii, everyone knows Gary, Nora and Cathy, but after that, who else is there, right? Then, people started coming out of the woodwork."

The editors had initially sought submissions through posts in the media and at the University of Hawaii Center for Korean Studies, but as word got around, people who had never been published started bringing in their work. "People would say, 'I don't know if this is what you're looking for, but I wrote this ...'"

Reading

Works from "YOBO: Korean American Writing in Hawaii"Where: Campus Center Ballroom, University of Hawaii at Manoa

When: 7:30 p.m. tomorrow, with 7 p.m. reception

Call: Bamboo Ridge Press at 626-1481

"It was a learning experience for us, to find that there is a whole community of Korean-American writers in our community," Kwon said.

IN MAKING THEIR story selections, Kwon said the first question the editors asked themselves was "How do I respond to this? Does this strike that chord inside me?"

"We were searching for stuff for a Hawaii audience," she said, "keying into a sensibility that's both Korean and local."

One writer in particular pulled at the heartstrings of the editors.

"What struck us initially about Wayne Wagner was the letter he wrote to us. He said he wasn't sure anyone would consider him Korean-American (his mother is Korean). We could tell he was taking a chance, that he wasn't even sure if he 'qualified' as Korean. We were taken by his earnestness to put himself on the line like that," she says.

As it turned out, the quality of Wagner's poetry equaled his poignant eagerness to share. His "When You Are Far Away From Something It Is Silent" is included in the anthology.

Another piece included in "YOBO," titled "The Glass Wall," was written by the late Victoria Sung Hye Chai Citron. Citron was mother-in-law to Joy Kobayashi-Citron, the managing editor of Bamboo Ridge Press.

"Her family was going through some of her things and found her writings," Kwon says. "No one knew she wrote creatively."

Kwon says the editors received lots of great historical and biographical works, but had to keep in mind that they wanted a true anthology. "We wanted poetry and fiction and artwork too. We kept that in mind throughout the process. And in the end, we looked at what we had put together, and realized, 'Wow!' We had quite a good range of works.

"We wanted to make it really organic, not only a singular voice. Fragmentation is something Koreans carry with them in their consciousness and in their language. We wanted to reflect that idea of multiple pieces -- how is unity made of pieces?"

THE EDITORS came up with the anthology's name while they were sitting at Jamba Juice, throwing out ideas.

"Someone said 'yobo,' and we all started laughing. But then we thought, 'why not?'

"Yobo is actually a term of endearment, used on special occasions with someone you feel a deep love for. The myth is that Koreans are called yobo because that's what Korean husbands and wives called each other on the plantations."

Kwon says that writing the anthology's introduction was a cathartic experience for the editors.

"We were aware of our Korean heritage, but when we started writing the introduction, we excavated very painful experiences we had had. We thought we'd come to terms with being Korean. But the anthology became strangely therapeutic and healing to us."

Kwon believes that the struggles of the cultural experience for Korean Americans are rooted the history of Korea.

"There are theories that the division of Korea has affected the psyche of Koreans," she says. "I tend to agree, when you look at history. The country has always had to defend itself from conquerors. And it's been divided for so long.

"You come to see division as almost natural. Like it's part of our racial memory to be divided."

Yet the editors of "YOBO" aspire to some form of cohesion. The introduction ends with short perspectives of the Korean-American experience. One editor writes:

"There's a seven-year difference between my sister Aileen and me. Joyce, our mother, saw how her older daughter had learned that everything Korean was poor, ugly and war-torn. She decided that would change with me. When I was a child, she showed me bright-colored hanbok and delicate silk pouches scented with sandalwood from the carved chest that held them. ... Eventually, everytime I saw something beautiful, I would turn to her and ask, 'Is this Korean?'

"But somewhere, that all disappeared. I succumbed to the same forces as my sister. Who wanted to be Korean? Why couldn't we be Japanese, like the rest of my friends?

"Only now does it occur to me how much that must've broken my mother's heart. How unfair it should be that, having shown me those treasures, I only saw trash.

"But I'm learning. It started by leaving, living on the mainland where yobo was tender, not derogatory. ... Visiting Korea for the first time since I was one, with my mother by my side. ... And finding, woven through the years, the delicate scent of sandalwood and dust.

"I'm learning my mother's lessons, the ones that taught me to be yobo: make 'Korean' and 'beautiful' the same word again."

"Take these stories," the introduction concludes. "Put the pieces together. Make them whole once more. Heal the body of our severed selves -- country, community, identity -- by calling each other gently, lovingly, 'Yobo.'"

BACK TO TOP |

‘The Glass Wall’

Here's an excerpt from Victoria Sung Hye Chai Citrón's "The Glass Wall" contained "YOBO: Korean American Writing in Hawaii":In the beginning, though we lived under the same roof, she never talked to me when we were alone. It never seemed necessary. We loved the same man: her son, my husband. It seemed enough. Soon however, I started to find in my room little packages or some choice fruit she had picked. This went on for some time. When or how she put them in my room without my ever seeing her was a mystery, but I knew it was her way of showing that she had grown to care more than a little for me. Whenever I thanked her for them or tried to do something for her, she would brush me aside or have something very urgent to do elsewhere. She always shied away from me when I got too close. When some of the older folks came to see her new daughter-in-law, she acted as though I didn't exist. And in this strange manner we grew to love and respect each other a lot more than we realized.

One morning I awoke dreadfully ill. I thought it was something I had eaten the night before so I went to see the doctor. Later, I could hardly wait for her to come home so I could tell her that she was to become a grandmother. When I heard the click of the gate, I ran out and hugged her and babbled out the news. I'll never forget the light in her eyes as for the first time she hugged me back.

From then on, she couldn't do enough for me and soon we had the first of our many talks about her family and her life. We talked about so many things, things I don't think even her children knew about. She became warm and lovable but was still so afraid to show her emotions. How often her joys and hopes must have been crushed or shattered to make her afraid to be herself. When I told her the baby was to be born in her home, the same home Butch had been born in, it was too much for her. She held me tight and rocked me in her arms as her shoulders shook with sobs so deep they seemed to come from the very depths of her soul. She had crashed through her glass wall.

Click for online

calendars and events.