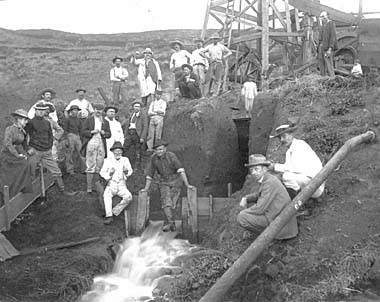

PHOTO PROVIDED BY BISHOP MUSEUM

Massive public-private investment in reforestation during the early 20th century replenished the water supply and fueled the era of plantation agriculture in Hawaii.

Watershed alliance

forming to fight

forest erosionHow to help

"Hahai no ka ua i ka ulu la'au"

(Rains always follow the forest)

-- Ancient Hawaiian proverbOne hundred years ago the native forests of Hawaii were in trouble.

Abuse, especially overgrazing by cattle and overharvesting of sandalwood, had destroyed thousands of acres on all islands.

Photographs from that time show shocking sights such as now-lush Nuuanu Valley looking like a treeless dust bowl.

It was clear to leaders of the day that if the destruction continued, there would not be enough water for sugar, maybe even drinking. Their solution was to create a forest reserve system that restored trees to barren hillsides and so preserved the water supply.

Gov. Linda Lingle was to mark the centennial of the state's forest reserve system today by establishing the Hawaii Alliance of Watershed Partnerships.

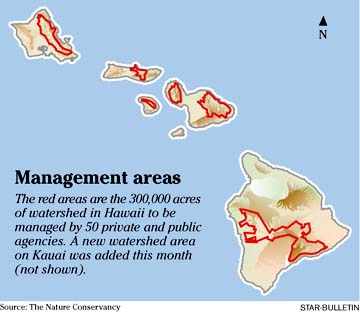

The alliance will promote coordination among the state's seven existing watershed partnerships -- and with new ones that are expected. Currently, 300,000 acres are jointly managed by 50 public and private partners to improve the watersheds. A watershed is a river valley and the surrounding areas that drain rainwater from the mountains to the sea.

Though there is no money attached, supporters say the watershed alliance will allow the groups to share ideas, resources and strategies, and make a stronger pitch for federal and private grants.

"I think it's monumental," said Avery Chumbley, president of Wailuku Agribusiness, which belongs to the West Maui Mountains Watershed Partnership.

"If you ignore the threat to the watershed, you're going to have a long-term effect far into the future," Chumbley said. After crisis was averted in the first decades of the 20th century by planting fast-growing, non-native trees, "for too many years we didn't pay attention to what's going on," he said.

In the 21st century, threats are to the native forests, mainly in the form of invasive plants and animals which destroy it when they live there.

"The 100th anniversary of Hawaii's forest reserve system is important because we would never have the quality of Hawaiian forest we have now without the early public and private partnership that made that happen," said Suzanne Case, executive director of the Nature Conservancy of Hawaii.

"On the other hand," Case said, "it's a time to renew and ramp up our commitment to forest protection."

"Most of us are down makai," Case said. "We look up and it's green and beautiful. We take it for granted. We don't realize there are significant threats of invasive weeds and feral animals destroying our forests."

The Nature Conservancy spends about $750,000 a year on watershed partnership projects that include things like fencing out hoofed animals like pigs and sheep, and removing forest-killing plants like miconia.

Kamehameha Schools spends more than $100,000 a year in four of the seven existing watershed partnerships, said Neil Hannahs, director of land assets for the trust.

State Forester Mike Buck noted that while Hawaii has the 11th-largest acreage of state forest lands in the country, its ranks 48th in spending on fisheries and wildlife. The whole Department of Land & Natural Resources receives less than 1 percent of the state budget.

Buck said the state spends $3 million to $4 million a year on forest reserves, but he believes more would be a good investment.

Today's focus is more on the native forest, which native Hawaiians see as integral to the survival of their culture and biologists warn is among the most endangered on Earth.

Said Hannahs, "These watersheds, as they approach the summits, they are wao akua, the realm of gods."

BACK TO TOP |

How to help Hawaii's forests

>> Volunteer to plant trees, build trails or other such activities.>> Hike in the forest; learn about it firsthand.

>> Clean your boots, backpack and camping equipment before entering native forest so you don't spread unwanted insects and weeds.

>> Pack out your trash; don't litter.

>> Don't release non-native animals -- like chameleons, tree frogs, parrots, rabbits or cats -- into a forest.

>> Report sightings of any non-native animals, like snakes or lizards.

>> Conserve water.

>> Keep fires out of Hawaiian forests. Native ecosystems don't recover well from fire.

>> Don't pollute streams and drinking water.

>> Learn more about Hawaii's unique natural heritage and how to preserve it.

>> Teach others, especially children, to care for the environment.

Source: The Nature Conservancy, Hawaii Department of Land & Natural Resources, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and Malama Hawaii. More ideas available at www.malamahawaii.org.

A brief history of Hawaii forests

>> When ancestors of native Hawaiians arrived in the islands in the fourth or fifth century, they immediately began affecting the forests. They used fire to clear lowland forests for crops, and harvested forest birds for their feathers. The pigs, dogs, rats and weeds they brought along all eventually hurt the forests. Yet their ahupuaa (mountain-to-sea) system of land management recognized that the upland forests were the source of fresh water.>> With European and American contact came more changes. Harvest of sandalwood for export to China extended environmental damage into the mountains. Mosquitoes that came on trading ships carried avian malaria, which eliminated native birds of the lowlands. Cattle and other livestock imported through the 1800s severely denuded forests.

>> On April 25, 1903, a Division of Forestry was established to bring back the forests that recharge the islands' underground aquifers. In its first decade, 37 forest reserves were established on 800,000 acres of state and private land. Hunting of feral animals and fencing to keep out livestock were employed along with tree-planting. By World War II most eroded areas had been restored, but with non-native trees.

>> A statewide Natural Area Reserve System was established to protect remaining native forests in 1970, and protection of endangered species became an issue. Current threats to native forests include invasive plants and animals that overpower native species and degrade the forests. Since 1991, watershed partnerships have been forming among public and private landowners in an attempt to improve conditions.

Source: The Nature Conservancy, Hawaii Department of Land & Natural Resources, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and Malama Hawaii