STAR-BULLETIN / 1999

Anyone who follows local news knows Haunani-Kay Trask as an advocate of Hawaiian sovereignty and self-determination for native Hawaiians, and knows that she sometimes addresses these issues -- and those she finds responsible for them -- with a directness that makes many uncomfortable. So it might come a surprise to those who know Trask only as political figure to learn about her softer side.

Words are the source of

strength in Haunani-Kay Trask's

outspoken sovereignty activism

as well as her poetic verseBy John Berger

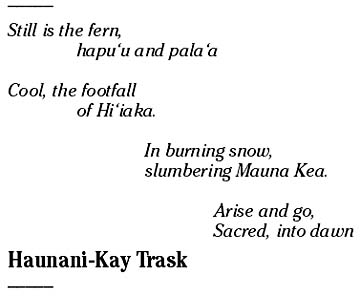

jberger@starbulletin.comIn the literary world she's recognized as a sensitive and articulate poet who has published two collections of her work, "Light in the Crevice Never Seen" and "Night Is a Sharkskin Drum."

Trask will read selections from the second book this month and next at Borders Bookstores on Kauai and in Hilo.

"There's no question that some of my poetry is very political, but to me it's two sides of the human being," Trask said last week as we talked the relationship between her public political persona and her role as a contemporary poet.

Featuring Haunani-Kay Trask Readings

Saturday: 2 p.m. at Borders Lihue, 4303 Nawailiwili Road, 808-246-0862

May 3: Noon at Borders Hilo, 301 Makaala St., 808-933-1410

Also: Trask will introduce poet Joy Harjo during a reading at 3 p.m. Thursday at the University of Hawaii's Kuykendall Hall 410. Free. For more information, call 956-7619.

"One side uses the nourishment in a public forum which is politics, and the other side uses the nourishment in an intimacy with the natural world, and since human beings are both pensive and active, if you want to put it that way, then both sides of us need that."

"Lecturing is the outside Haunani-Kay Trask side. That is the side that's political, that is hard-driving, that is always making a case for civil rights and sovereignty and, for years, a Hawaiian studies building -- a place for us in our own land -- that is the political argumentative normative Haunani-Kay Trask. The poetry is the internal native daughter who connected with the past and the culture and the field of augmenting that."

Trask says she began writing poetry in high school, inspired in part by one of her teachers and in part by her mother, who also enjoyed reading and writing poetry. Other members of the Trask family composed music; Haunani wrote poetry.

"I think for lots of Hawaiians it's very natural. Any kind of metaphorical work, whether it's in song or in chant or, in my case, poetry ... It's a beautiful inheritance."

Trask says she draws her inspiration from the land and finds it next to impossible to write poetry when she's away from the islands."The internal communal connection with yourself, and through yourself, is whatever inspires you. In my case it's the land and Hawaii in general. That's a very private connection, and it's very nourishing because the rest of the my life is politics."

Trask acknowledges that some of her poetry is indeed "politics in another form." Several of the most instantly striking pieces in her new book are aggressively so -- "Nostalgia: VJ-Day," "Smiling Corpses" and "Dispossessions of Empire."

Others may be less abrasive but still provide focused snapshots of an occupied nation in which "aloha" is a commodity and the "slow-footed Hawaiians" find themselves marginalized and almost irrelevant in an economic system run by immigrants "claiming to be natives."

Those expecting only political poetry will be surprised to find that there are perhaps as many examples showing her skill in romantic verse as well. The language is English but the ambience is Hawaiian, and the verses rich with implied kaona (hidden meanings).

She says she can see "my land" -- breadfruit and coconut trees, the Koolaus, passing clouds and occasional waterfalls -- as she writes.

"Even if you're alone there's so much around you. Given that the other side of me is politics -- which does not nourish you -- the land and the flowers and the trees is where my inspiration comes from even when I'm writing about sad things."

Trask also finds spiritual nourishment in the works of other poets. Two of her favorites are Caribbean-born poet Derek Walcott and Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish.

"(Walcott) writes an enormous amount ... and he has such a connection with the whole sense of light, for example, which is so important to me because Hawaii has the most fabulous beautiful light. The light in the morning where I live is so gorgeous, even when it's raining.

"His work is very inspirational to me because I realize we have the same relationship to light. I've never been there, but he describes it in a way that is very like Hawaii."

Trask says much of Darwish's work describes experiences similar to those of native Hawaiians.

"His work is filled with a sense of place and loss and suffering that comes with not having a homeland. In his case, he was there when Israel was created, and he writes of being separated from the little plot of ground where he grew up and the enormous tragedy. ... (His poems) have a sense of their place that you don't have if you're reading a history book or a travel book. You need that internal connection between a poet and the land, and when that communicates to you the reader, not only is the poet fulfilled, but the reader is fulfilled.

"I've heard from people who told me they'd been to Hawaii 45 times and never even thought about the native people, the land and other ways to seeing history. They're tourists, and I've always wanted to ask them where they found the book."

Trask says that she grew up just before the "re-legalization" of the Hawaiian language, and therefore writes her poetry almost entirely in English using Hawaiian names for historical and cultural figures, geographical locations and in places where the Hawaiian word is better suited than a English equivalent. Few people speak and read Hawaiian fluently -- even in Hawaii -- so she included an eight-page glossary that provides translations and short explanations of the cultural significance of some items.

"I've been criticized for it, but I'm trying to help the reader," Trask said.

"Critics say it loses the mystery of the poem, but I don't know what they mean. The poem is mysterious enough. It doesn't need to confound the reader with words they don't understand, and I think it's kind of a purist view, 'Take it or leave it.' If that's the case, then why publish? It means so much to a writer to hear someone far away say that they were moved by your work, and if you don't have a glossary, those people are never going to understand it."

Closer to home, Trask says that nothing touches her more deeply than being told that her poetry has inspired young Hawaiians to follow in her footsteps as authors and poets.

"No recognition could be more comforting and congratulational than that."

Click for online

calendars and events.