UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII Chiune Sugihara, right, shown with wife Yukiko, saved thousands of Polish Jews during the Holocaust.

It's thanks to Steven Spielberg and his dark epic, "Schindler's List," that Americans know of Oskar Schindler, a German businessman who, during World War II, spent the money he made in German-occupied Poland by bribing Nazi officials to spare the lives of Jewish slave laborers who worked him. He ended up saving the lives of more than 1,000 people. Exhibit honors

Japanese diplomat who

helped refugees flee NazisA little-known consul issued

visas to Jews in Eastern EuropeBy John Berger

jberger@starbulletin.comAmerican stamp collectors and historians also know Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg, who risked his life to save thousands of Jews from Nazi persecution in war-torn Hungary but died in a Communist concentration camp sometime after the war.

In recent years Americans have been learning about a third such hero, Chiune Sugihara, a Japanese diplomat who sacrificed his career so that Jewish refugees might live. The Visas for Life Foundation will bring his story to Honolulu tomorrow when an exhibit honoring Sugihara opens at the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii. The opening will include two free showings of a film on the subject, "Visas For Life," and a free public reception that will be attended by Sugihara's widow, Yukiko, and son, Chiaki.

Shaoul Levy, who had commissioned a life-size statue of Chiune Sugihara as a memorial in the Little Tokyo district of Los Angeles, underwrote the expenses involved in bringing the Sugiharas from Japan for a weeklong goodwill tour in Hawaii to coincide with the exhibition opening. Another benefactor, Seymour Kazimirski, paid the costs of shipping the exhibit to JCCH (materials will also be on display at the University of Hawai'i Hamilton Library).

Anne Hoshiko Akabori, volunteer executive director and chair of the Visas for Life Foundation, explained that the foundation also addresses related areas of Japanese culture and "that period of Japanese history." It's a fascinating story.

Where: Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii, 2454 South Beretania. Reception for Yukiko

and Chiaki SugiharaWhen: 5:30 p.m. tomorrow

Admission: Free

Call: 945-7633.

Also: "Visas For Life," a documentary about Chiune Sugihara, will be shown before and after the reception at 3:30 p.m. and 7 p.m. Admission is free.

CHIUNE SUGIHARA was a diplomat who worked in the Manchukuoan Foreign Office and as a member of the Japanese Legation in Finland before he was posted to Kaunas (Kovno), Lithuania, in October 1939, where he found himself in a tricky position.

Germany and Japan were moving into a defensive alliance to improve their position relative to the British Empire and the United States. The Japanese expected the new alliance would deter the U.S. and England from attacking Japan and persuade the two "Anglo-Saxon Powers" to allow Japan more freedom in East Asia. However, Nazi Germany already had an ally in the Soviet Union. In theory, that made Japan and the Soviet Union allies too, but imperial Japan was also staunchly anti-Communist, and there had been several battles between Soviet and Japanese forces along the Manchukuoan border.

Soviet forces invaded Lithuania on June 15, 1940, and foreign diplomats were ordered out of Kaunas in July. Sugihara, who spoke fluent Russian, asked for a 20-day extension. He spent much of that time issuing "transit visas" for Jewish refugees.

A "transit visa" allowed the bearer to pass through one or more nations en route to somewhere else. A Dutch Jew, stranded in Lithuania after the Germans conquered Holland, discovered that a visa as such was not required to enter Curacao, a Dutch colony in the Caribbean, and that the sympathetic Dutch ambassador to Latvia, L.P.J. de Dekker, would gladly provide Jews with a document, even though he knew that people without a landing permit would not actually be allowed to enter Curacao. The ambassador instructed every consul in the area that they could provide such a document to anyone who asked for it. The honorary Dutch consul in Kaunas, Jan Zwartendijk, had a stamp reading "No visa to Curacao is required," and applied it to passports, ID cards, and even on sheets of paper bearing a refugee's name.

Unfortunately for the refugees, the Netherlands did not have diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union, and the Russians wouldn't allow the Jews to travel unless they could provide proof that they would be accepted into another country after they reached Vladivostock.

Sugihara knew that few countries wanted Jewish refugees -- particularly Jews fleeing Nazi persecution in Germany or German-occupied Poland. He asked his superiors for instructions and was told that transit visas allowing passage through Japan could only be issued to people with an end visa, with a guarantee of departure.

Sugihara knew that few, if any, of the refugees would qualify. He discussed the matter with his wife and decided to disobey his orders and issue as many "transit visas" as possible, making it possible for thousands of Jewish refugees to cross the Soviet Union and enter Japan.

Local Jewish community and Jewish charity organizations helped care for the refugees, who were also of interest to the Japanese government. Sugihara's superiors had, in essence, ordered him to ignore the Jews' plight, but there were other factions in the Japanese government and Imperial Japanese Army who believed that aiding Jewish refugees from Nazi genocide might earn Japan the gratitude of American Jewish groups, and that this might then cause the Roosevelt administration to adopt a more even-handed policy toward Japan.

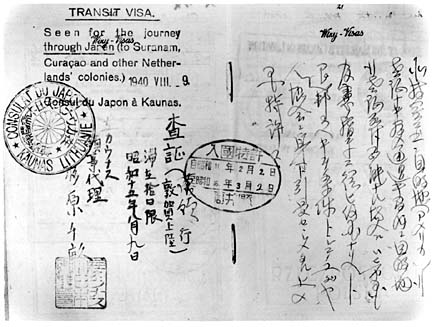

COURTESY IMAGE

A 1940 Japanese transit visa.

This didn't happen, and Roosevelt did not allow the refugees to travel on to the America, but the refugees remained safe in Japanese-occupied Shanghai for the duration of the Pacific War, and the Japanese ignored Nazi "requests" that they be killed.

SUGIHARA'S WARTIME career continued with postings in Bohemia-Moravia, Germany, and Romania. The Soviet Union attacked Japan in the final month of the war, and Sugihara and his family spent 16 months in a Communist concentration camp after the war ended. When they returned to Japan in 1947, he was asked to resign from the foreign service and lost his rights to a pension because he had disobeyed orders by issuing the transit visas.

Sugihara eventually built a new career, but decades passed, during which his acts of humanity went virtually unnoticed. He was eventually honored by the Israelis with a Yad Vashem Award and park created in Jerusalem in his honor.

Sugihara died in 1986, and won posthumous honors from the Japanese Foreign Ministry in 2001.

"(Americans) virtually know nothing about it," Akabori said of Sugihara's role in establishing Japan's role as a refuge for victims of Nazi persecution. Few Americans know that the Japanese government even put forth a plan to settle more than 500,000 Jewish refugees in Manchukuo. Unfortunately for those who might have been saved, the proposal depended on American support and funding, and the Roosevelt administration wanted nothing to do with it.

Many other diplomats disobeyed orders to help Jewish refugees before and during World War II. Eric Saul, project director of "Visas For Life: The Righteous Diplomats Projects," counts more than 120 diplomats from 27 nations who helped Jews escape Nazi persecution.

Like Sugihara, they often paid a high price for their actions. Aristides de Sousa Mendes do Amaral e Abranches, a Portuguese diplomat in wartime France, issued hundreds of "documents" -- each good for a single person or an entire family -- that would allow the bearer or bearers to enter Spain en route to Portugal in spite of orders to provide no visas.

When Abranches was ordered to return to Portugal, he escorted a final group of refugees across the Spanish border to safety.

Abranches, who was married, with 14 children, was fired from the diplomatic service and lost his pension. His son John Paul Abranches, now retired and living in California, says that the Jewish community in Portugal stepped in to help the family survive, and made it possible for him to attend school in the U.S.

While Akabori concentrates on educating Americans about Sugihara's role in aiding Jewish refugees, Saul is researching the contributions of other diplomats and making their stories available.

When Chuine Sugihara was asked years later why he disobeyed his superiors' orders and issued the visas, he put it this way: "If I didn't, I would be disobeying God."

Click for online

calendars and events.