THE STRESS FACTOR

|

Some kids lag Vern Dahl, a lanky 6-footer who counsels elementary students, sees a major stumbling block for Hawaii's public schools looming right at the starting gate.

from the start

Maui's Kamalii Elementary

helps children succeed with a special

transitional class for first gradersBy Susan Essoyan

sessoyan@starbulletin.com

More children showing up for kindergarten just aren't ready for it, he said, and they tend to lag their peers academically for the rest of their school years.

Why teaching and learning at Hawaii's public schools can be more difficult than it should be.

"They get pushed along, become discipline problems and they're recommended for special ed," said Dahl, a counselor at Kamalii Elementary School in Kihei, Maui. "Many of these kids simply don't belong there if they'd acquired the reading skills in kindergarten and first grade."

His school has come up with a simple solution that has dramatically cut its special education enrollment -- bucking a statewide upward trend -- and helped boost overall student achievement. Most important, he said, it has turned kids who might otherwise have felt like failures into successful learners.

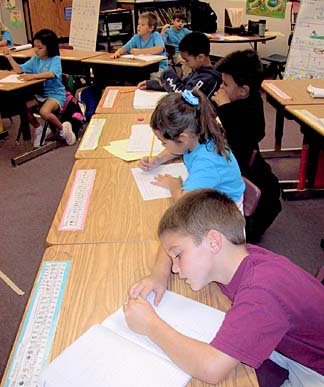

The school carefully assesses incoming students and places them in kindergarten classes geared to their level of ability, with one functioning at almost a preschool level. Children who are still struggling at the end of kindergarten spend a year in a transitional first-grade class before having to tackle actual first grade.

"We don't want to put kids back to the beginning of kindergarten, but if they can't handle first grade, we have to have some kind of halfway house," Dahl said, noting that the decision ultimately is up to the parents.

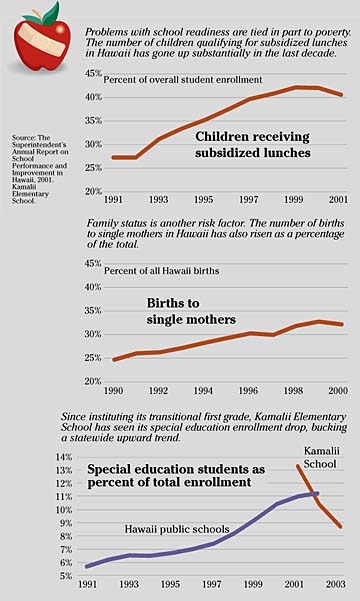

Problems with school readiness are rooted in poverty, family status and physical immaturity, studies show. Recent trends in Hawaii on those fronts have not been encouraging.

The number of children qualifying for subsidized lunches, a common measure of poverty, jumped to nearly 41 percent from 27 percent in the past decade, state Department of Education data show. Meanwhile, births to single mothers, another risk factor, grew steadily to 33 percent of total births from 24 percent.

Hawaii's kindergartners, already among the nation's youngest, now start school younger than ever, with half of all public schools on year-round calendars, beginning in late July. (See story on raising the kindergarten age.)

|

"Kindergarten teachers suggest that over half of their students enter their classrooms unprepared," the Hawaii School Readiness Task Force said in a report to the 2003 Legislature. The report calls for a multipronged effort by the public and private sectors to help get children ready for kindergarten.

It cited a national blue-ribbon study issued recently, "From Neurons to Neighborhoods," which found striking disparities in what children know and can do before entering kindergarten. The report concluded that "these differences are strongly associated with social and economic circumstances, and they are predictive of subsequent academic performance."

"We've got kids who come to school knowing virtually everything on the kindergarten readiness test, and other kids who know virtually nothing," Dahl said. "Age is the largest factor but it isn't the only one. A lot of them come from families that don't have the time or money to give the kids experiences to get them ready for school."

Since setting up the transitional classroom in the 1998-99 school year, Kamalii's special-education enrollment has dropped steadily, to 67 students (8 percent of the student body) in December 2002 from 89 (10 percent) in December 2001 and 113 in December 2000 (13 percent). The school has nearly 800 students in all.

Meanwhile, children who went through the transitional first grade are doing remarkably well, according to Dahl, who worked for 30 years as a testing and measurement consultant for publishing companies before becoming a counselor.

"We have 70 to 80 kids in our school who have had that extra year, and they are all scoring in the average range or higher," he said, "all of them. And they had to be in the bottom range to start with."

The school assesses all its students three times a year to help keep them on track, using the Star Early Literacy testing program in kindergarten and the Star Reading test in first through fifth grade. The interactive, computer-based tests take less than 20 minutes and provide immediate feedback.

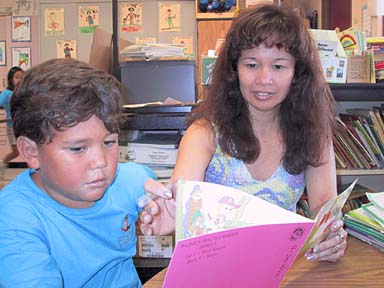

Parent Lori Hazen said the transitional year made a huge difference for her son Tyler, who is now in fourth grade. He reads well above his grade level and has devoured all the Harry Potter books.

In kindergarten it was a different story.

Tyler was one of the youngest in the class, with an Oct. 27 birthday, and had trouble with the fine motor skills needed for writing.

"It was hard for him even to hold a pencil in the beginning of kindergarten," Hazen recalls. "He's a very bright boy. The eye-hand, fine motor skills were the big issue. That really held him back.

"I didn't want him to always wonder why he was the worst at things," she said. "He needed that time. He has done extremely well."

Last April, the median score on the Stanford Achievement Test for reading for Kamalii's third-graders, which includes members of its first transitional class, such as Tyler, was in the 60th percentile. That was a substantial leap over the previous group of third-graders tested at the school, who scored in the 48th percentile in April 2000.

Cheryl Bisera, who has taught the transitional class since its inception, said it is heartening to watch children who once were "fearful of raising their hands and saying the wrong answer" step up to the plate and succeed.

"They just need that one little extra year, just to be able to mature and feel good about themselves," she said. "Once that has taken place, they have taken off."

Bisera taught a regular kindergarten class for 13 years and found it "so stressful" to try to reach and engage children of widely ranging capabilities. "I find it easier, for myself, not having that broad range of abilities."

Kihei resident Mary Kahawaii said she's happy to have her 6-year-old son Shem in Bisera's class. With a December birthday, Shem was a young kindergartner and had not attended preschool, so he had trouble focusing on school work.

"I would sit and try to read with him. He would run away," said Kahawaii, who now volunteers in his class. She said many of the students are smart but just need time to develop social and learning skills.

With its new facilities, air conditioning and school uniforms, Kamalii looks like a private school to some observers. But it is a regular public school. It did not need any special permission to institute the program, and the price is right, too, according to Principal Sandra Shawhan.

"That K-1 position comes out of the first-grade allocation," she said. "It doesn't cost us any more to do the program than if we didn't have it."

Karen Ginoza, president of the Hawaii State Teachers Association, said the union favors instituting "junior" and "senior" kindergartens in the public schools where necessary, to help give kids who need it the extra time to get on a solid footing, and has suggested it to the Department of Education.

"The plan we have proposed would not have taken much more money," she said, "but they didn't buy it."

Schools Superintendent Pat Hamamoto said she was familiar with the idea, and "we'd have to look at more details on it."

The school system already is having to watch every dollar it spends, trimming $3 million from its budget between now and the end of the fiscal year in June, and bracing for further cuts. But with the cost of special education soaring, programs that will help keep children on a successful track in regular school deserve support, advocates say.

"It's a preventive measure that we're doing," Dahl said, "so we don't need the crisis intervention to such an extent in the upper elementary grades and higher."

Star-Bulletin reporter Gary T. Kubota contributed to this report.

|