The Rising East

Chinese spin

Web of dissentBetween 10,000 and 15,000 Chinese dissidents, members of the Falun Gong religious sect, quietly filed into Tiananmen Square in Beijing on April 25, 1999, and sat down in orderly rows outside of Zhongnanhai, the posh residential quarters for China's political leaders next door to the ancient imperial palaces within the Forbidden City.

The silent protest against government repression had been organized and marching orders issued almost completely on the Internet by e-mail and Web sites, plus wireless telephones. It was all out of sight of Beijing's ubiquitous security police and caught them flat-footed. It took the cops 18 hours to react and drive the dissidents away.

Thus began a battle of wits over the political use of the Internet between Chinese dissidents and China's government and ruling Communist Party, with Falun Gong, the China Democracy Party and the Free Tibet movement among the leaders. A new study by the Rand Corp. in California says the authorities have the upper hand at the moment but that time and tide may be on the side of the dissidents, with unpredictable consequences.

The Rand study, authored by James Mulvenon, a specialist on China, and Michael Chase, a researcher on information technology, has a catchy title for a publication from a sober-sided think tank: "You've Got Dissent."

The Internet has expanded swiftly in China, mostly among young, educated people in big cities along the eastern seaboard. In 1999, there were 2.1 million Internet users in China; at the beginning of this year, that had soared to 31.7 million. The number of computers connected to the Internet leapt from 747,000 in 1999 to 12.5 million this year, the Rand report says.

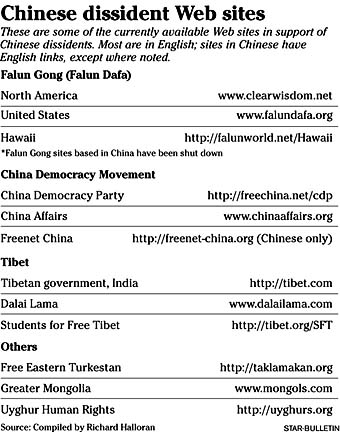

For Falun Gong, e-mail has been vital. When the sect's founder, Li Hongzhi, fled to the United States in 1999, he set up e-mail lists to communicate with adherents back in China and new supporters in the states. He set up a secret press conference in Beijing to condemn police beatings and disseminates articles on Minghui Net's Web sites (available in English at clearwisdom.net).

Several members of the CDP told Rand researchers that "use of e-mail and the Internet was critical to the formation of the party and allowed its membership to expand from about 12 activists in one region to more than 200 in provinces and municipalities throughout China in only four months." The dissidents have set up a dozen Chinese-language Internet bulletin boards.

The Free Tibet movement, under the leadership of the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala, India, has Web sites based in London, Washington, New York, Canada and Switzerland. One site offers information in 18 languages. Another, the Rand study says, "seeks to motivate and coordinate Tibetan independence support." A third works to raise money. Tibet was invaded in 1949 and subjugated by China in 1951.

Mulvenon and Chase argue that "China faces a very modern paradox" in the Internet. Chinese leaders see the development of information technology "as an indispensable element in their quest for recognition as a great power." At the same time, the authors say, "China is still an authoritarian, single-party state with a regime whose continued rule relies on the suppression of anti-regime activities."

To counter the dissidents, Chinese authorities have turned to both low-tech and high-tech solutions. The low-tech includes standard Leninist tactics: shutting down networks, using informants, and surveillance of and arresting suspected dissidents. In March 2001, for instance, security officers arrested software engineer Yang Zili for maintaining a Web site he called his "Garden of Ideas." His computer and other items were confiscated.

High-tech approaches include blocking Web sites and e-mail, hacking into dissident systems and monitoring the e-mail of foreign visitors as well as suspected dissidents. The authorities also insert disinformation into the Internet. Fake articles attributed to Li Hongzhi, for instance, have been sent to Internet users in China.

"The mixture of the two has proved to be a potent yin and yang, deterring most anti-regime behavior and neutering whatever remains," the Rand report says.

Even so, the authors assert, that "does not lead inexorably to the conclusion that the regime will continue to be immune from the forces unleashed by the increasingly unfettered flow of information across its borders."

Richard Halloran is a former correspondent

for The New York Times in Asia and a former editorial

director of the Star-Bulletin. His column appears Sundays.

He can be reached by e-mail at rhalloran@starbulletin.com