Mauna Loa data LOS ANGELES >> Atop Mauna Loa, thrust 13,677 feet into the sky, one would expect nothing but the freshest air, save the occasional gaseous burp from the volcano.

show pollution

is global

Substances such as arsenic in

Hawaii's air come from ChinaBy Andrew Bridges

Associated PressBut environmental monitoring stations crowding the peak find arsenic, copper and zinc that was kicked into the atmosphere five to 10 days earlier from smelting in China, thousands of miles distant.

When industrial pollution first showed up at Mauna Loa a few years ago, scientists were startled. Now, after intense study, they know that the pollution that dirties the world's largest cities affects the whole Earth.

"It turns out Hawaii is more like a suburb of Beijing," said Thomas Cahill, a University of California, Davis, atmospheric scientist.

Along the West Coast, a campaign to measure the pollutants as they make landfall after bridging the Pacific ends this month.Since April, scientists have used data gathered on the ground and from an airplane flying along the coast to measure aerosol pollutants that waft eastward each spring, carried by the prevailing winds. For the United States, China is a major source. For Europe, it's the United States, and likewise down the line, complicating the blame game.

"It's kind of a natural human condition to point to someone else who is causing your problems," said David Parrish, a research chemist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. "Each state points to the state upwind and says, 'You're causing our problems.'"

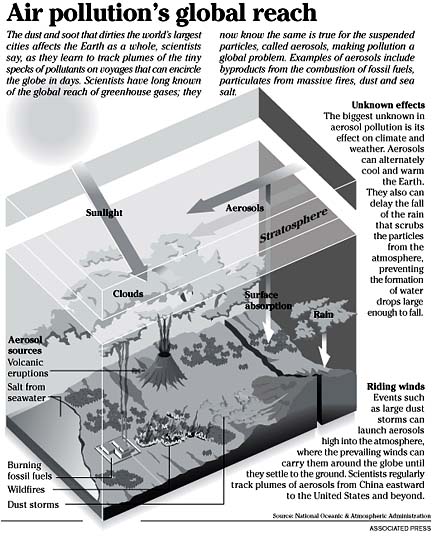

Scientists previously supposed only greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide were so global in reach and effect. They now understand that the microscopic, suspended particles of pollutants, generically called aerosols by atmospheric scientists, wrap the globe, even if they persist for just hours before settling to the ground.

This class of pollutants includes soot, salts, dust and other byproducts of the burning of fossil fuels and vegetation.

"It happens on a small scale, but the implications are on a global scale," said V. Ramanathan, an atmospheric scientist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

During their time aloft, the particles affect everything from global warming to human mortality to the rainfall that ultimately scrubs them from the atmosphere. Given their tremendous variety in shape, size, composition and distribution, their effects are unpredictable.

Scientists long thought aerosols were day-trippers, settling close to their point of origin. In fact, many are. The big cloud of smoke, dust and pollutants from the attack on the World Trade Center didn't travel very far, researchers note.

Beginning in the 1950s, scientists began noticing layers of haze in places like the Arctic, far from any significant source of pollution. The haze suggested aerosols were capable of traveling jet-setter distances.

Large storms can hoist a plume of particles high enough to hook up with the jet stream. Once high enough, dust from the Sahara or smoke from big fires "can easily travel halfway across the globe," said Yoram Kaufman, a senior scientist with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Once plugged into higher altitude winds, the sometimes vibrant plumes can be charted.

The best example is the billowing clouds of dust kicked up each spring in Mongolia's Gobi Desert. That dust blows east, passing through cities like Beijing. There, the particles of dust are frosted by various pollutants, many of them toxic. The noxious confection continues to blow eastward, arriving in the United States within days.

There, its effects are dramatic: In May 1998, Cahill and others measured the highest atmospheric concentrations of arsenic ever seen in the western United States in tiny Jarbidge, Nev., population 12.

"It's nothing that is going to get anyone sick. It's just that it shouldn't have been there," Cahill said.

Aerosols have been tracked from the Sahara to the Caribbean, from Ontario to Rhode Island, and from Germany to Sweden. Within them travel toxic metals, nutrients, viruses and fungi.

"We live in a small world. We breathe each other's air," Cahill said.

Nor is the problem new: Pollutants generated by the smelting of ores by the Greeks and Romans show up today, more than 2,000 years later, in trace amounts in ice cores drilled from Greenland.

"These dust plumes don't go away right away. They can be carried over great distances and are forcing people to take a global perspective on pollution," said Barry Huebert, a professor of oceanography at the University of Hawaii.

The effects of aerosols are obvious in cities like Beijing, where the springtime mantle of dust and pollution cuts visibility to feet.

The tiny particles make for spectacular sunsets, but they also pose a serious health hazard, as they can lodge deep in the lungs, contributing to increased mortality.

Aerosols may also harm agriculture by blocking portions of the spectrum of light from the sun, effectively starving crops like wheat and rice of the energy they need to grow.

The biggest worry, and the one least understood, is the effect aerosols have on weather and climate.

Some aerosols can cool the planet by literally shading it from the sun. Others can warm it by absorbing and trapping the sun's heat.

"(Aerosols) are clearly right at the center of some important climatic issues," Huebert said.

Aerosols may also have the peculiar ability to aid in the formation of clouds, while retarding their rainfall, scientists reported in a study in the journal Science in December.

Water drops will coalesce around aerosols in clouds, but not clump together to form the larger drops that gravity pulls from the sky as rain.

"We humans may be pushing precipitation away from populated regions," said NASA's Kaufman.

The dust is not all bad news, though; the wafting plumes also carry nutrients to regions that depend on them. In Hawaii, plant life relies on Asian phosphorus and calcium to grow. Phytoplankton -- those bottom feeders of the food chain -- in the waters off the Alaskan coast crave Asian iron, which blows eastward by the millions of tons.

Still, scientists believe it's important to trace the origin of the pollutants and say they can do that by using the unique chemistry of aerosols as a fingerprint.

Ken Rahn, a professor of oceanography at the University of Rhode Island, has developed a roster of about 150 compounds, each with its own distinct signature. With some work, scientists can distinguish between soot from a power plant burning low-sulfur coal in Colorado and a fire raging in the Brazilian rain forest.

"Once the scientists say these particles are coming from here, here and here, at that point it's finger-pointing," said Ramanathan, who has proposed a national effort to study aerosols. "That's something we have to leave to the politicians to figure out."