|

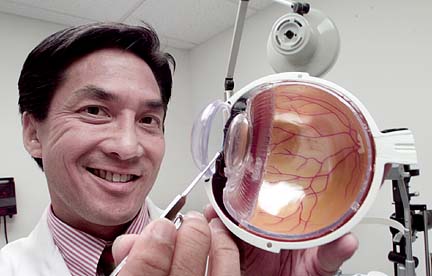

DR. M. Pierre Pang says he's "just a little guy working in a little hospital," so he was floored by the responses to his study related to cataract surgery.

Hawaii ophthalmologist M. Pierre

Pang has found that lidocaine might

not be necessary in preparing

patients for cataract surgeryBy Helen Altonn

haltonn@starbulletin.comA retinal specialist, Pang compared two methods of numbing eyes for such surgery in a research project at St. Francis Medical Center-West in Ewa Beach.

Most ophthalmologists in the United States use the more invasive method of intracameral lidocaine -- injecting anesthesia into the eyes -- to reduce pain and light sensitivity, said Pang, Department of Surgery chairman at St. Francis-West and surgeon director of the Pacific Eye Surgery Center.

The other technique is simply to use anesthetic drops to numb the eyes, he said.

Ophthalmologists have long debated the benefits of intracameral lidocaine injections, Pang said.

"I got into a big discussion with colleagues. Some people are thinking it decreases pain; some are saying it decreases light sensitivity. I wasn't sure why I was using it. I wanted to find out."

What he found is, "It really doesn't help," he said.

"We showed all a patient needs for successful cataract surgery is a little intravenous sedation, which makes the patient sleepy ... and little drops of anesthesia to numb the eye, and they do really well."

Unexpectedly, his research team also discovered the eye's macular vision is better after cataract surgery. "We didn't know that; it is not shown in literature," Pang said.

The macula is a light-sensitive area in the center of the retina.

"At first we thought injecting anesthesia into the eye could be toxic to the retina," Pang said. "Quite the contrary. Retinal function improved."

Working with Pang on the study from August 1999 to mid-2000 were Dr. David Fujimoto, optometrist in the Pacific Eye Surgery Center, and Lynne Wilkens, biostatistician at the Cancer Research Center of Hawaii.

The American Academy of Ophthalmology's journal Ophthalmology published the results last November, triggering a deluge of calls from other medical publications, ophthalmologists and national experts wanting copies of the study, Pang said.

"I was really taken aback by it. I had no idea I was going to receive this type of response."

Ocular Surgery News, which he said is "like the New Yorker for doctors," reported the study in its March issue.

It was the first study of its kind, testing the two anesthetic procedures on 15 patients who had cataract surgery in both eyes. The usual studies look at separate sets of patients, each with surgery in one eye, then compare techniques on the different patients, Pang said.

In his study, each mildly sedated patient had salt water injected as a placebo or substitute anesthesia in one eye and lidocaine injected in the other eye. Topical anesthetic drops were put in all eyes.

Pang said some patients reported stinging and pain when lidocaine was injected in the eye. But generally, there was no difference using lidocaine or salt water to fool the other eye.

He said 80 percent of the patients had no discomfort, regardless what method was used.

The findings are significant for three reasons, Pang said:

"You want to remove as many extraneous steps as possible. If giving an inject of anesthesia in the eye doesn't help, why do it?

"At a higher dose, anesthesia is shown to cause corneal damage.

"Third, if you inject anything into the eye, you can't make sure it's a pure substance. There could be impurities which could cause infection in the eye, which would be disastrous."

Using just topical anesthetic eye drops with a little intravenous sedation not only has excellent results, but reduces costs of the anesthetic and possible risk of corneal damage, he said.

About the same time his study was released, Pang said, the American Academy of Ophthalmology recommended using lidocaine injections to numb eyes for incremental pain control only when it cannot be managed with anesthetic eye drops alone.

As part of Pang's research, Fujimoto conducted sophisticated electrophysiological tests -- measuring the electrical response of the retina to light stimulation -- on both eyes of five patients after cataract surgery.

Pang said it was surprising to discover improved macular function, which "helps us to understand why patients see better following cataract surgery."

All patients studied had visual acuity better than 20/40 in both eyes, and 93 percent had corrected sight of 20/25 or better one month after the surgery, Pang said.

He said vision loss reported in some cases after lidocaine injection into the eye appears related not to the drug, but to high pressure from the injection closing off an artery "and kind of creating a small stroke in the eye."

Pang said he is working on a new project "that will be even better. It will really be a boost for cataract surgery -- the most common (eye) surgery in people over age 55," he said.