|

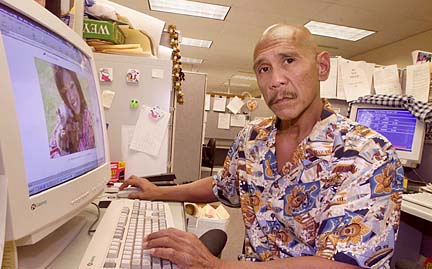

Web of deceit Cybercrime gets no more low-tech than that demonstrated by Pyong Kun Pak. Over a six-month period, the 33-year-old South Korean living in Honolulu used the identities of 30 people to order goods costing as much as $300,000 on the Internet.

Hawaii ranks No. 2 in the nation

in the rate of Internet fraud, a pace

driven by the rapid rise in identify theftBy Lee Catterall

lcatterall@starbulletin.comHowever, Pak did not obtain the Social Security numbers, birth dates and other confidential information from the World Wide Web. In cyber lingo, his source was brick-and-mortar, what Honolulu Police Detective Chris Duque calls "non-tech avenues" -- typically, credit card receipts taken from trash cans, bills pilfered from mailboxes, receipts retrieved from gutters.

As the Internet has ballooned in recent years, so has Internet crime. Much of it goes unreported, absorbed by companies as part of the cost of doing business on the Web or by credit-card companies preferring to pass the cost on to their customers through high interest rates.

|

Of the economic cybercrimes that are reported, Hawaii residents are more likely than people in any other state to be victims.In the old days, Duque says, people used the telephone to order goods under false identities, and the person taking an order was able to at least know from the voice on the other end whether the customer was a man, woman or child.

"When you're online," he says, "you don't know who it is or where it's coming from. The vendor really doesn't know."

Pak relied on the anonymity of the Web in using Social Security numbers and other information to pretend to be other people and order scores of computers through the Internet from December 1999 to April 2000. Only when a Maui victim was called by a friend at a shipping company on the island to tell him about the arrival of a laptop computer he hadn't ordered did Pak's scam begin to unravel.

Several months later, Honolulu police tracked down Pak at a Waikiki hotel. He was caught after leaping from the lanai of a second-story room he had rented under the name of Henry Tacub. (He also used the name Peter Pak.) A search of his pockets turned up a packet of methamphetamine and a glass smoking pipe. Pak is believed to have pawned off the computers he had ordered to pay for his drug habit, according to Deputy Attorney General Christopher Young. His booking sheet lists his occupation as "forger."

|

In December, Pak entered into a plea bargain with the Attorney General's Office, agreeing to plead no contest to 16 counts of theft, attempted theft and computer fraud, pay restitution of $109,410 and serve a maximum prison term of 10 years.Pak is the first Hawaii resident known to have parlayed identity theft into Internet fraud on a large scale, according to Young and Duque. Similar frauds, although smaller, now are "a common occurrence," says Duque, who has been in charge of investigating cybercrime at the Honolulu Police Department for eight years.

U.S. Attorney General John Ashcroft last week called identity theft "one of the fastest-growing crimes in the United States," victimizing 500,000 to 700,000 people a year, and called on Congress to approve longer sentences for offenders. Identify thefts were estimated to have cost U.S. financial institutions $2.4 billion in losses and expenses in 2000.

Fraud exists in many other forms on the Internet, led by misrepresentations at online auctions, which accounts for nearly 43 percent of all complaints, according to the Internet Fraud Complaint Center, a partnership of the FBI and the National White Collar Crime Center. That does not include nondelivery of merchandise and payment, which accounts for more than 20 percent of the complaints.

Making Internet fraud difficult to combat is the likelihood that perpetrators and victims are in different jurisdictions, requiring long-distance cooperation of multiple law-enforcement agencies. Even in California, where much of the fraud originates, only one-fourth of the cases involve the suspect and victim being within the state's boundaries.

Before the Internet, crimes usually occurred within a single jurisdiction, Duque adds. "Now your mamasan-papasan store becomes global."

Mainland perpetrators of fraud are drawn to Hawaii "because we're so far away," with a different time zone, no adjoining states and high costs of extradition if the perpetrator is caught, he says.

Duque believes that is why Hawaii's rate of 8.9 Internet fraud victims per 100,000 population is second in the nation only to the District of Columbia. Hawaii ranks fourth in the country in identity theft complaints per capita, on or off the Internet.

Jason Tadao Ibara's Internet fraud was more sophisticated than that perpetrated by Pak. The 29-year-old Honolulu man provided hosting services on an online shopping center, auction house and classified advertised section, promising investors as much as 20 percent in commissions based on sales. Ibara's company took in $1.27 million from more than 100 investors, according to federal authorities.

FBI Special Agent William Denson said the only way Ibara's operation could make money was through new investments. He likened it to a pyramid scheme. Ibara pleaded guilty to fraud in federal court in August and faces $250,000 in fines and five years in prison at his sentencing scheduled later this month.

National e-commerce fraud losses last year exceeded $700 million, about 1.14 percent of online sales, according to GartnerG2, a Stamford, Conn., firm. That ratio was 19 times higher than the fraud rate for traditional in-store transactions, which was less than a tenth of 1 percent.

"We're not going to see low fraud rates like we have in the brick-and-mortar world until we make some serious changes in the way that online business is conducted," says Avivah Litan, Gartner's vice president for research. "There are some big issues to deal with."

One is the tendency for Internet crimes to go unreported. Federal law holds consumers liable for only the first $50 of fraudulent charges made on their credit-card accounts. Credit-card companies are held liable for anything beyond that, as long as the fraudulent charge was accompanied by a signed -- or forged -- receipt. On the Internet, such validation doesn't occur, so the merchants -- most often computer companies, as in Pak's case -- bear most of the cost.

"A lot of times we don't get these cases because the companies won't even report it," says Young. "The computer companies will just absorb the loss because it's not worth their time."

Meanwhile, many businesses that operate online underestimate the need for security measures to protect their computer systems. A survey of 50 Hawaii businesses taken recently during the previous 18 months showed that a "very high percentage of local businesses lack the most elementary security safeguards," says Richard Marine, president of Century Computers in Honolulu.

Twenty percent of the companies lacked firewalls, which protect online computer systems from outside entry, and 70 percent had neglected to update their software to patch flaws that had been detected.

"They're complacent," Marine says. "The biggest reason is, they ask, 'Why would somebody want my information?' My point is, they don't. That's not the purpose of a lot of attacks. They do it because they can. They don't want your information. They just want their kicks."

Computer hacking, whether for monetary, malicious or political purposes, or just for kicks, has become a major expense and source of concern for operators of Web sites, whether public or private. At companies, hacking causes deprivation of online business for expensive periods of time needed to restore service.

Over the past several years, hackers have vandalized Web sites operated by the state Legislature and the University of Hawaii but were stopped by firewalls from penetrating the computer system at last year's Asian Development Bank conference.

In a 1997 military exercise called Eligible Receiver, a group of National Security Agency officials were given two weeks to determine the vulnerability of U.S. military and civilian computer networks. Using software obtained from hacker sites on the Internet, the NSA hackers, based in Hawaii and other parts of the country, broke into unclassified military computer networks at the headquarters of the U.S. Pacific Command, as well as networks on the mainland.

The government's computer security has dramatically improved since then because of heightened federal security standards, says Marine, whose company's clients include government and military agencies.

"In the last year, I've seen a lot of the government installations that we're dealing with go through some type of due diligence or audit on what level of security they're putting in," he says. Still, he adds, they could be more secure.

"They're not where they really should be," Marine says, "but budgets don't allow you to go very far with it."