![]()

Think Inc.

A forum for Hawaii's

business community to discuss

current events and issues.

![]()

Think Inc.

A forum for Hawaii's

business community to discuss

current events and issues.

What's a local company? | Air merger bid revisited

|

|

UNDERSTANDING

THE ECONOMYRedefining

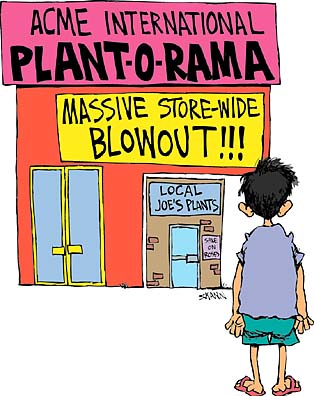

a local companyIs it always bad to buy

By Eric Abrams

from a mainland chain?A while back, I received a call from a telemarketer trying to get me to subscribe to a local newspaper. I was told that these subscriptions help create college scholarships for the delivery people. I found it quite odd that rather than telling me what a wonderful newspaper it was, they told me of how I'd be helping out local kids. If I want to help local kids go to college, nothing is stopping me from doing so on my own.

Clearly our local newspapers are not locally owned, so were they trying to give the impression that they are to get me to buy their product? So what if they are not locally owned; is this what defines a local company?

Suppose I want to start some home improvement projects. I have a choice of where to buy the materials -- I can buy from Home Depot or I can buy from City Mill. Yes, there are others, but let's keep it simple.

My observation is that on identical (or very similar) products Home Depot has lower prices than City Mill. This means that I can actually take the money I've allocated to home improvement and start more projects by purchasing from Home Depot instead of City Mill. Alternatively, if I only have one project to complete then I could take the savings from shopping at Home Depot and celebrate the completion of the project by going to a nice restaurant. So, I can get more for my money by getting the lower price. Unfortunately, many people see the following as a downside.

Home Depot is not considered a local company. Many people think this means that the money spent there leaves the island. So let's think about this. The money goes to pay for the inventory and salaries, amongst other things. While most of their items are not from here, many are. Many of the plants, for example, come from nurseries that are here in Hawaii.

Salaries are paid to the employees who live here and, not surprisingly, spend much of that money here. I'm not trying to convince everyone to shop Home Depot instead of City Mill; I am stating that "non-local" companies do not take all of the money they receive off the island. Much of that money gets redistributed here.

In my mind, this makes such companies local in that they do indeed help the local economy. How many people would be jobless if Home Depot left the state? How much less in taxes would be paid to the state? On top of that, higher prices would be paid by contractors and homeowners alike, which would result in less construction, something that is always bad for an economy.

So please keep in mind the following. Just because a business isn't locally owned doesn't mean it doesn't help the local economy. Also, business owners should keep in mind that when it comes to spending, people like to receive value. This means getting the most for your money. The lower the price you pay, the more money you have left to buy more stuff.

Eric Abrams is an associate professor of economics at Hawaii Pacific University. He can be reached at eabrams@hpu.edu. BACK TO TOP

|

The merger of Aloha

By Jack M. Schmidt Jr.

and Hawaiian would not

have solved market illsOn the very morning the merger between Hawaiian Airlines and Aloha Air Group was called off there were still a surprising number of Hawaiian employees and others who were saying that this was a "done deal." Which only goes to prove that people who think that there is such a thing as a done deal haven't done many deals.

Hawaiian and Aloha operate in the two lowest-yielding airline markets in the world. The interisland system is the lowest-yielding short-haul market in the world. The West Coast to Hawaii is the lowest yielding long-haul market in the world. Most Greyhound bus fares on the mainland are higher per mile than those charged by Hawaiian or Aloha for an interisland airplane seat. Clearly something needed to be done to rectify this, but was an under-financed "merger" of the two carriers the answer?

The facts began to show rather clearly that this was nothing more than a cash grab. If consummated, nearly $40 million of the two airlines' cash would go out the back door, in part to provide lavish golden parachutes for senior management. John Adams of Smith Management, Hawaiian's controlling shareholder, would have received at least $16 million. He and his partners would continue to retain their stock ownership and, in fact, would receive 1 million additional shares of the new company absolutely free. Slightly smaller sums would have been paid to Glenn Zander of Aloha and Paul Casey of Hawaiian. Deal-broker Greg Brenneman, who would have become CEO, was being paid $100,000 a month even if the deal fell through, would have received more than $1.8 million per year plus "living expense" and 20 percent of the stock of the new company, also absolutely free.

On top of all this, another $70 million in new debt would have been added. Brenneman attempted to persuade the shareholders of Hawaiian, the employees, and the community at large that, despite an initial burden well in excess of $110 million (cash plus debt), this new airline would somehow be better positioned to grow and be profitable than either of the two airlines were separately. And if that were not enough, Brenneman stated publicly that he intended to borrow even more money from banks once the deal was closed.

From the onset Brenneman created a significant problem for himself by his characterization that this was somehow a "merger of equals," thereby immediately alienating virtually all of Hawaiian's employees, their relatives and friends. The following data reported by Air Transport World magazine indicated that this would have been anything but a "merger of equals."

>> In 2000, Hawaiian had operating revenues of $607 million. Aloha's were $283 million. For the seven-month period from January through July 2001, the two airlines produced the following: >> Hawaiian carried 3.56 million passengers. Aloha carried 2.89 million. >> Revenue passenger kilometers flown: Hawaiian, 5.06 billion. Aloha, 1.16 billion. >> Available seat kilometers flown: Hawaiian, 6.34 million. Aloha, 1.66 million. >> Freight ton kilometers flown: Hawaiian, 42.2 million. Aloha, 8.0 million. These data show clearly that this was not a merger of equals. In fact, about the only area where it could be called that was in total employment. Hawaiian employs about 3,500 people, Aloha about 3,000. However, with only 17 percent more employees than Aloha, Hawaiian flies some 400 percent more revenue passenger kilometers.

A key benchmark used in analyzing an operating company is "revenue per employee." Based on the data above Hawaiian produced more than $173,000 per employee. Aloha generated only about $94,000 per employee.

Very few people employed by Hawaiian are unhappy with their lot in life despite having made substantial sacrifices in pay and benefits in years past to do their part to help the company recover from its previous financial misadventures. Now Hawaiian is not in any imminent danger of collapse. Why should any of the minority shareholders, employees or the traveling public trade the known for the unknown unless there was a clear benefit? No one seemed able to offer a compelling reason.

It's clear now that Brenneman committed a major tactical blunder by initially characterizing this as a "merger of equals." He would have had a much better chance if, in the beginning, he had set his sights on Hawaiian and simply stated, "I plan to take control of Hawaiian and I'm going to grow the hell out of it and make it a major force in the Pacific. If Aloha wants to join in, I'll take a look at what they have to offer and pay them accordingly. If not, we'll still use the anti-trust exemption made available to the carriers following the 9/11 attack to coordinate interisland operations and to deal with the ticket wholesalers who make it impossible for either of us to show a profit in the local market."

Just what was Aloha going to bring to this party? They apparently had about $20 million in cash. An immediate offset to this cash would have been a $10 million payment to redeem unmarketable, restricted securities (Aloha stock) that Aloha's management contributed to an "underfunded pension obligation." Additionally, $4 million would have been paid to Zander as severance pay. This would have left a scant $6 million remaining.

It appears that the aircraft of choice for the interisland fleet would have been the Boeing 717 currently operated by Hawaiian. Since Aloha's 737s are destined to be made into beer cans, what else, other than some old ground equipment, would they have contributed?

Every single Aloha pilot, flight attendant and dispatcher would have required complete retraining. Their ground service people would have needed retraining on the 717, 767 and DC-10 aircraft operated by Hawaiian. All their reservationists and station personnel would have required training on the Sabre system used by Hawaiian. Their crew schedulers and people in their training, flight standards and other operational areas would have needed significant on-the-job training before they could have been very productive.

What about Aloha's routes? Infrastructure investments at Aloha's interisland destinations would have been of little value to Hawaiian because it already operates to these same destinations and has developed its own extensive facilities.

Aloha's mainland service is of questionable value as well. Assuming Hawaiian even elected to continue serving these cities, it's doubtful that Oakland and Orange County could support more than three or four frequencies per week with the type of aircraft it has in its fleet. Other than the opportunity to eliminate it as an interisland competitor, acquiring Aloha will do nothing for Hawaiian that it was not already doing or planning to do in the near future.

So the question remains: What was Aloha bringing to this party? Answer: Not much. What was Hawaiian paying for it? Answer: A lot.

But wouldn't the new airline have been able to expand to all sorts on new destinations? Just what on earth would acquiring Aloha have to do with that? Answer: Absolutely nothing. Hawaiian already has the equipment available (or on order) as well as the necessary people on staff (or on furlough) to provide all the new service that the Hawaii market can support for the foreseeable future. From June 15, 2001, to June 15, 2002, Hawaiian will have added or reinstated five Hawaii-mainland services. Brenneman knew that it is not prudent or possible to add service any faster than Hawaiian is currently doing.

Brenneman's stated goal of adding service to Japan (and other Asian markets) was a gratuitous attempt to play on cultural sympathies. He knew full well that there is no open-skies agreement with Japan and any new routes for U.S. carriers must first be negotiated between the U.S. State Department and the Japanese Foreign Ministry in the form of a new bilateral air service agreement. These normally take several years with no guarantee that, if successfully consummated, Brenneman's new carrier would have been selected to provide the service.

According to SEC filings, the two carriers have experienced post-Sept. 11 losses on the order of $75,000 to $100,000 per day for Hawaiian and $109,000 to $170,000 per day for Aloha. Taking the lower figure for each and equating these losses first to total revenue and then to revenue passenger kilometers flown, the following picture emerges:

On the basis of year 2000 revenues (the latest reported by Air Transport World), Aloha's losses are equal to nearly 14 percent of its daily revenue while Hawaiian's losses are equal to about 4.5 percent of daily revenue. Using traffic figures for the first seven months of 2001, Aloha's losses per revenue passenger kilometer are more than six times those of Hawaiian.

It doesn't seem likely that Aloha's losses are due totally to the alleged "destructive competition" in the interisland market. If this were the case, since both carriers have about an equal interisland market share (and presumably similar losses in that market), Hawaiian's transpacific service would have to have been subsidizing its interisland operation by as much as $70,000 per day or $25.5 million per year to drive its daily losses down to the $100,000 per day reported in the filings. It's more likely that Aloha's losses stem mostly from its ill-conceived plan to extend service to various mainland cities; a money-losing operation that Hawaiian does not need but would end up paying a substantial premium to acquire.

Perhaps most of Hawaiian's losses during the same period can be attributed to the fact that it has been completing the phase-in of one new aircraft type and initiating the phase-in of another, all at great expense. In response to the Sept. 11 disaster, Hawaiian suspended two mainland-Hawaii services. It also lost a major charter contract when the customer went bankrupt.

Late in the game the danger signals finally became apparent to Hawaiian's board. This was a very risky undertaking which could have resulted in the failure of both companies. They wisely chose to hold all parties to the original time limit specified for the completion of all approvals for the transaction, knowing full well they could not be met, thus condemning it to a natural death.

The key attractions of Brenneman's scheme were to have been new and increased service, a rapid return of laid-off personnel and a move to profitability -- features which, according to Brenneman, could only occur if the two carriers merged. Yet within days of the death of the deal Hawaiian announced a substantial increase in its service and the recall of all its furloughed flight attendants.

A few days later it announced a $16.7 million operating profit for 2001.

Jack M. Schmidt Jr. has been a pilot with Hawaiian for 17 years.

To participate in the Think Inc. discussion, e-mail your comments to business@starbulletin.com; fax them to 529-4750; or mail them to Think Inc., Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 7 Waterfront Plaza, Suite 210, 500 Ala Moana, Honolulu, Hawaii 96813. Anonymous submissions will be discarded.