|

Think of 200 Hiroshima-size atomic bombs going off at once.

Scientists say Hawaii's killer-wave

Woman recalls fleeing 1946 waves

warning system will work --

as long as people listenBy Helen Altonn

haltonn@starbulletin.comThat's the awesome power of an earthquake measuring 7.5 on the Richter scale, said Brian Yanagi, state Civil Defense earthquake and tsunami program manager.

"Basically, the earth is ripping apart, rupturing underground and displacing water."

The result could be a catastrophic tsunami reaching Hawaii within three to six hours, Tsunami Warning Center and Civil Defense officials emphasize.

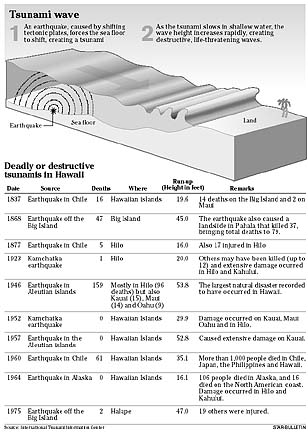

April 1, 1946, was a dramatic example: An earthquake in the Aleutian Islands triggered a tsunami that killed 159 people: 96 in Hilo, 15 on Kauai, 14 on Maui and nine on Oahu. It was the worst natural disaster in Hawaii's history.

|

The largest local earthquake historically was in 1868, with a tsunami causing 47 deaths. It caused a landslide in Pahala that also killed 37.With April observed as Tsunami Awareness Month, officials are urging residents to learn more about killer tsunamis and be prepared for the one they think inevitably will happen.

They are worried because Hawaii has not been hit by a Pacific-wide tsunami since 1965. Since a whole generation has never experienced the deadly phenomenon, they fear people will pay no attention to warnings.

"Even all of us at the center have had no experience with a big tsunami striking Hawaii," said Charles McCreery, director of the Richard Hagemeyer Pacific Tsunami Warning Center at Ewa Beach.

Tsunami warnings are issued immediately for Big Island earthquakes greater than 6.8 magnitude because waves can strike parts of the Big Island and Maui in five to 10 minutes and reach across the state. Residents are told to head for higher ground when they feel the ground shake.

|

There were no tsunamis after the last two warnings, in 1994 and 1996, but the experiences exposed problems that led to changes in procedures, said Gerard Fryer, University of Hawaii geophysicist and state tsunami adviser. For example, an evacuation plan was developed to prevent gridlock in Waikiki.Traffic jams occurred across the island because people got into their cars unnecessarily, Civil Defense officials said.

Harbors also were clogged as people ran to their boats to take them to sea. "A lot of them ran out of gas and had to be towed back," Yanagi said, advising boaters not to leave too close to a tsunami's arrival time.

Officials urge residents to study evacuation maps in the front of their phone books. If a warning is sounded and they are not in a danger zone, they should stay where they are. Those in an evacuation area, whether at home, work or play, should go to higher ground. Free express buses will shuttle people to shelters.

No one should leave protected areas until an all-clear is issued.

Click image below for larger version

Two other big problems are surfers and spectators.School was canceled after the March 27, 1994, warning, and hundreds of kids were in the surf at the North Shore when the tsunami was expected.

"If a significant tsunami occurred, it might be their last ride," said Dan Walker, tsunami adviser to the Oahu Civil Defense Agency.

People going to beaches just to see a tsunami would likely be swept away by waves roaring up on shore. "They are putting themselves and rescuers in harm's way," Yanagi said.

A tsunami is a series of ocean waves caused not only by earthquakes, but underwater landslides and submarine slumps, and they could go on for several hours, the scientists said.

In 1933, when Hawaii was hit by a tsunami from an earthquake in Japan, the eighth wave was the largest, more than two hours after the first one, Walker said.

A tsunami appears as a rapidly rising tide or wall of water; the waves do not curl and cannot be surfed, the scientists said.

Walker has calculated that tsunamis ran up on shore as much as 54 feet on Molokai in 1946. A resident told him fish were found in the trees, as well as seaweed.

Scientists and emergency managers must work quickly within a short time span to analyze an earthquake and determine the potential impact of a tsunami. They may issue a tsunami advisory or tsunami watch and finally a warning if it is possible waves could arrive within three hours.

"We're looking at over 400,000 residents and tourists on the coastline in the worst-case scenario," Yanagi said. "It's a nightmare to evacuate in three hours."

McCreery said there have been a lot of improvements in the system, but there will probably still be false warnings because of difficulties forecasting the impact of a tsunami on the state.

The last scare was June 23, when the largest earthquake in Peru in 30 years caused a big tsunami. A Hilo policeman told Yanagi by phone that the bay was draining.

Fryer said they were "on the threshold of a warning," with 11:30 p.m. as the possible arrival time, but decided after getting enough information that it was not big enough to cause damage here.

Among the latest developments enhancing the warning network are six deep-sea tsunami detectors, McCreery said. Three are off the Aleutians, two off the West Coast and one south of the equator to pick up tsunamis from South America.

Walker also has installed eight sensors at inland sites on the Big Island, mostly on the Kona Coast, to measure locally generated tsunamis. If water hits them, they can sound a siren on an instrument farther down the coast and send an alert to the Ewa Beach warning center.

BACK TO TOP

|

The six-year-old girl wasn't scared when neighbors took her and her little brother from Keaukaha, hacking their way through the jungle with machetes, to escape the Big Island's great tsunami on April 1, 1946. [ TSUNAMI AWARENESS MONTH ]

Woman recalls

fleeing 1946 wavesBy Helen Altonn

haltonn@starbulletin.com"Initially I was thrilled because I didn't have to go to school," said Jeanne Johnston.

Years later, watching a slide show by University of Hawaii professor Walt Dudley of the devastation, she said, "All of a sudden, I had a physiological reaction. My heart was beating so fast ... I thought I was going to jump out of my skin."

Johnston, now living in Kailua, and her brother, Dr. David Branch of Seattle, were living with their mother and grandparents when the tsunami hit. Branch then was 4 years old.

"Most of my memories are snapshots of the day, like rolling film," Johnston said.

She and her brother were walking toward the road about 7 a.m. when the first small wave flooded the yard and took out the road, trapping everyone in the area, she said.

The second wave destroyed most houses. It picked up her grandparents' house and dropped it in the yard, with her grandfather in it, she said. "It started as a three-story house and ended up as a two-story."

Her uncle, Rod Mason, got her and her brother out with a group of people who cut their way through the jungle to reach the FAA tower at the airport, she said.

They walked over rough aa lava covered with water rising through the rocks, she said. "We couldn't run fast on bare feet. We were all badly lacerated."

Her grandmother, mother and uncle remained on high ground at neighbors' houses. Her grandfather, Charley Mason, watched the third wave from his front porch. "He was an old seaman (from Scotland). He wouldn't leave the ship," Johnston said.

When the house started to move, she said, "My grandfather dove into the second floor of the house from the porch."

When she and her brother returned about 2 p.m. along the same path through the jungle, they saw a house in the middle of the road with an arm sticking up, she said. "So many people were killed."

Reaching their grandfather's house, they found him sitting on a wall with a bread box full of Hilo Macaroni pilot cookies -- "his favorite thing," Johnston said. He had put guava jelly and peanut butter on them. "He made this food for us and was waiting for us to come back."

Her uncle and grandfather went into town, where her grandfather "found the first phone to call a contractor to fix his house," Johnston said.

She didn't understand what was happening that April 1, although she heard people screaming and crying, she said. However, her mother said she and her brother had nightmares for months, she added.

"In 1946, nobody talked about disasters. People just cleaned up and went on with their lives." It wasn't until the 1990s, when she was working on a genealogy and the older people had all died that she realized she had not asked them any questions.

After reading "The Tsunami," written by Dudley and Scott Stone about the 1946 tsunami, she contacted the UH scientist looking for pictures of her grandparents' house. He had none of Keaukaha, but people were sending him more information, and he asked her to show him where it was, she said.

She began collecting stories from other tsunami survivors and decided a museum was needed. She talked to Dudley and Hilo families and got a group together in November 1993 to start the Pacific Tsunami Museum in Hilo. More than 200 videotaped and audiotaped survivor stories, some film clips and many still photos now are archived there.