|

Dragon’s blood Look up, past the wooden crates and bins filled with dried black mushrooms, ginger and choi sum, past the storefronts full of blue and white ceramics and lucky bamboo. Look up at the stone facades of Chinatown and you will see the names of men once wealthy, renowned, visionary and/or infamous on building cornices, a lasting reminder of their prestige.

Pam Chun weaves a family history

'Money Dragon' roars with drama

rich in intrigue into fictionBy Nadine Kam

nkam@starbulletin.comYet, three generations after the buildings went up, few can match a face to the names. Even families forget.

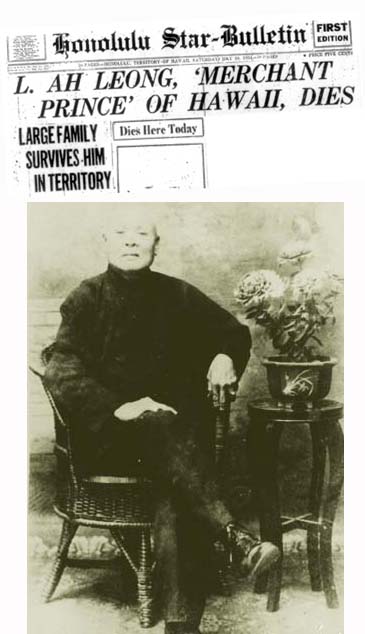

Such was the case of Lau Fat Leong, better known as Lau Ah Leong, one of the founders of Honolulu's Chinatown. As a boy he was penniless and considered worthless, not worth saving when he nearly drowned. Upon moving to Hawaii, he went bankrupt in one business before finding success as a merchant in Honolulu.

He was one of a few men who had the ability to tread between two worlds -- that of immigrants and ali'i in monarchial times and that of the white businessmen, bankers and politicians. At one time, he owned a chunk of land bordered by Beretania, King, River and Maunakea streets plus estates in his ancestral village of Kew Boy in the Meishan district of Southern China. But in a few decades his story might have been lost forever, had it not been for a chance conversation between Lau's great granddaughter Pam Chun, and former United States Sen. Hiram Fong, who said he had known Lau well. It was the first time Chun, then 40, had heard the name.

|

FOR CHUN, WHO said she had grown up poor, gaining admittance to Punahou School and the University of Hawaii only through scholarships, the revelation set her on a 10-year odyssey to learn her family's story, and what a story it turned out to be -- Hawaii's own version of "Dynasty" with polygamy, greed, jealousy, rivalry, thievery and an all-out bitchfest involving five wives and a ghost."All those years, ever since I was a little girl, I'd go shopping with my grandmother in Chinatown, carrying her bags up and down the street, and she never said a word about my great grandfather," Chun said. "And one day I looked up and saw the sign. All this time his name had been there."

Chun started asking questions, only to be confronted by what she calls the "Chinese wall of silence."

"No one would tell me anything. All my aunts and uncles would say, 'There's nothing good to say about that.' They were protecting the family. They didn't want the kids to kearn certain things or be concerned.

"I understand why people wouldn't want to talk when there's a trauma in a generation. That's why it always takes the third generation to write the stories. I think as a grandchild I had a certain amount of leeway. They forgive you a lot."

|

Chun had moved to California to attend UC-Berkeley and stayed there to work as a marketing consultant in the high-tech industry. It was only after she started showing her family documents she had discovered at the National Archives in San Bruno, Calif., that they became interested in sorting the myths from facts. Even Chun's grandmother, who at first only answered questions with a mumbled "Ummmmm," came around."I'd show her pictures and say, 'Look, it's grandfather,' and she'd look out of the corner of her eyes and say, 'He looks pretty good there. He must have been young.' "

Chun has since transformed her family's story into a novel, "The Money Dragon," which, like Milton Maruyama's ground-breaking novel "All I Asking For Is My Body, juxtaposes a family tale with the history of one particular immigrant group in Hawaii. In Maruyama's case, it was the Japanese. In Chun's case, it is the history of the Chinese from the monarchy to the early days of American annexation.

In the book, Chun sometimes breaks the thread of fiction to offer a few history lessons for context.

"People have said they're glad I wrote this. It has a lot of history, it has a lot of culture in it. They say it's good that our history is out there; it's taken so long."

In the National Archives, Chun discovered a goldmine of history of Chinese immigrants who entered the country through Angel Island and Honolulu.

"Because of the Chinese Exclusion Act, every Chinese who entered the country had to go through extensive interviews that were demeaning and tough, but it really preserved the history. Immigration officials not only required documentation backed by birth certificates and other paper records, but oral recitation of entire genealogies, along with dates of birth of parents and siblings, marriages, occupations, addresses, travel dates of family members and reasons for travel.

|

"A lot of people have told me they would flunk on their own families if they had to do that today," Chun said, "and he had a large family with 10 sons and 11 daughters."In addition, returning Chinese had to have witnesses who could vouch for their identities. Because of his status, L. Ah Leong could call upon prominent Honolulu businessmen and officials, both Caucasian and Chinese, including City Mill founder C.K. Ai.

IN SPITE OF those difficulties, Chun found there were ways to cheat the system. Some entered the country as "paper sons" -- she found none in L. Ah Leong's family -- who memorized the details of others' lives to pass through; others simply bribed the immigration officials. The magic amount was $1,350 and Chun said all Chinese knew this number.

"When officials in Washington heard about this they send an investigator and one immigration official committed suicide. They found he had amassed a half a million dollars. That was a huge amount of money for that time."

Chun said she was inundated with files and it took her a long time to sort through the names. It didn't help that one individual might be known by three names -- a Chinese name, nickname and Westernized name.

"It was like a puzzle, a mystery," she said.

Chun initially pieced the information together as a historical document, but her agent convinced her the story might be easier to digest as fiction, focusing on her great grandfather, rather than trying to track all the movements of all wives, sons and daughters.

"There were so many threads, it would have been confusing for a lot of people, and Ah Leung's story is strong in itself, about how he started as a poor person when his father lost the family fortune, how he went bankrupt himself, to how he became wealthy, and like King Lear makes bad decisions."

Those decisions would ultimately destroy the empire he had worked a lifetime to build.

"My editor said it had the feel of 'Dream of the Red Chamber' or 'Raise the Red Lantern,'" Chun said, "and I wanted to tell it like my grandmother told it to me, in stories that make up the big picture."

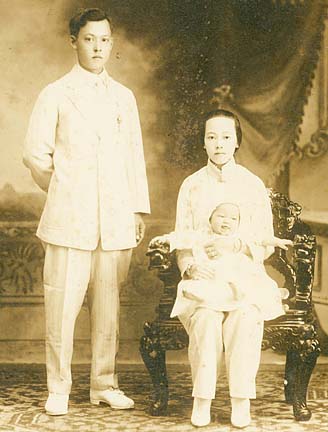

The story is told from the perspective of Chun's grandmother Phoenix Chong Fung-Yin Lau, who marries Lau's first son Tat-Tung (he gains that status after eldest son Lau Ah Yin runs away to California to escape their unloving mother, Lau's first wife Fung Dai-Kam).

Eventually, the family story becomes a political, legal test case pitting the old Hawaii against the new as Lau and second wife Ho Shee attempt to use American laws to negate Fung Dai-Kam's common law status, established during the monarchy.

"Now that I know this background, I realize that's what makes us what we are," Chun said. "The women in my family have always been outspoken and strong-willed. Well, there's a reason for that. They had to stand up for themselves.

"Our ancestors were living in a time when men had the power. If he said his first wife was his wife, she was his wife. If he said she wasn't his wife, she wasn't his wife.

"You know those days were like the Wild West. A man could get away with anything if he had the money and power and name.

"My grandmother started telling me the stories when she was 90 years old. That was when she started slowing down and she wasn't cooking or working in the yard. She finally had time to sit down and talk to me, and it was like a door that opened and she started remembering more and more.

"She started to give me pictures because she said no one else would appreciate them."

Phoenix did not live long enough to see Chun's finished work. She died last year at age 102. If there is a lesson to be learned from Chun's experiences, she said it is important for families to write down their histories.

"You may not think it's important, but how about your grandchildren? How will they know? I wish I had known all this as a child."

As to whether animosity between the relatives still exists, Chun said she never had the opportunity to interact with descendants of Lau's other wives.

"We never saw each other. If we did we knew we were related but didn't know how. I would really love it if all the descendants could get to know each other because we have this incredible history to pass down."

Information about the National Archives and Records Administration

can be found at http://www.nara.gov/regional/ sanfranc.html.

BACK TO TOP

|

It's easy to imagine Pam Chun's first novel as a prime-time soap opera. It has family intrigue, betrayal, romance (OK, matchmakers are involved, but so is honest love), all set against a backdrop of wealth and power. ‘Money Dragon’ roars

with intricate, juicy dramaReview by Betty Shimabukuro

bshimabukuro@starbulletin.comMost important, it has the critical characters: a mercenary lead male with an overactive libido; a bitch-on-wheels matriarch; a pure-hearted central couple.

Some television producer should buy the rights now.

"The Money Dragon" is fiction based on Chun's own family history. It's a fascinating story, especially enlightening for all of us who can identify with its cultural underpinnings.

Set in Honolulu in the first part of the last century, "Money Dragon" tells the story of L. Ah Leong, the real-life merchant who amassed a fortune through his ability to straddle the worlds of the Chinese immigrant and the haole elite. His store was Chinatown's foundation.

Yet the plot largely turns on the women of this massive family, beginning with the formidable first wife, Dai Kam, whose fortitude and strong back were essential to his empire. The way he turns on her in their later years is the stuff of great, juicy drama.

Both husband and wife considered girl babies "a waste of rice"; of 10 born to the family, seven were given away. Dai Kam considered Ah Leong's four lesser wives and her daughters-in-law to be her slaves, tolerating her husband's infidelities because they brought her more subordinates to mistreat.

Chief storyteller is Chun's own grandmother, Phoenix, wife of first son Tat-Tung. The author gives this couple all the positive qualities that the rest of the family lacks. Everyone else is greedy and conniving; they are reasonable, loyal and able to love girls.

They seem like regular folk, until you come across a passage like this one: "My labor pains began after Tat-Tung left for work and the children were in school. I gathered the sheets, boiled the water and knife, and waited."

It's a clear reminder that Phoenix lived in a whole other world, and one that encompasses a tremendous range of human emotion.

Yep. A TV producer should buy the rights, NOW.

"The Money Dragon"

By Pam Chun (Sourcebooks Landmark, 352 pages, hardcover, $24)

Book signings

Pam Chun will be signing copies of "The Money Dragon" at the following locations:

Thursday

>> Bestsellers, Bishop Square, 12:30 to 1:30 p.m.

>> Native Books and Beautiful Things, Ward Warehouse, 6:30 to 8:30 p.m.

Saturday

>> Bookends in Kailua, 600 Kailua Road, 11 a.m. to noon

April 1

>> Ramsay Museum in the historic Tan Sing Building, 1128 Smith St., 5 to 7 p.m. RSVP by calling 537-ARTS (2787). Park at Mark's Garage.

Click for online

calendars and events.