|

Oahu's Sandy Beach is known the world over as a top bodyboarding and bodysurfing spot.

The waves are great,

but so is the risk

Thrill seekers ignore caution

signs and lifeguards' warnings

of frequent injuriesBy Diane Leone

dleone@starbulletin.comAnd for its high proportion of ambulance calls.

"This beach requires a great deal of expertise, and even the experts get hurt," says Jim Howe Jr., Honolulu City and County's chief of lifeguard operations.

"To use the analogy of ski slopes ... it's a double black diamond run."

Year after year, Honolulu lifeguards make more rescues at Sandy Beach per beach user than at any other beach they guard.

|

In 2000, there was an average of one rescue for every 3,000 people who visited Sandy Beach. By comparison, about 58,000 people sunned and swam at Waikiki before one needed a rescue.To put it another way, only 3 percent of the people who went to the beach on Oahu in 2000 went to Sandy Beach, yet 16 percent of the rescues were there.

"It's probably the most active beach on the island, because no matter what direction the swells are coming in, it's never a lake," says lifeguard Robert Dorr. "Sometimes it gets small, but that's a rarity."

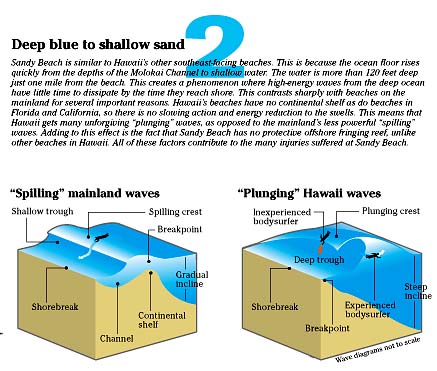

The waves aren't as big as the famous surf of the North Shore or Makaha.

But they break right on the steep-sloping shore. That means anyone riding the waves needs to know how to get out before they crush them.

The force of the waves, Dorr says, "is the equivalent of getting hit by a car. It could easily knock you out."

|

Up in the lifeguard tower on a recent Thursday, the lifeguards talk to each other as they scan the beach. Billy Goodwin is watching two young women in knee-deep water who don't look wise to conditions."Oh, those girls," he says in anticipation. "Oh," he repeats, as they get pounded by a wave that quickly surges waist-high, forcing them to balance against each other as they struggle out of the backwash -- laughing.

"It's all fun and games until someone gets hurt," Goodwin comments, just as the girls are knocked down by a second wave.

Minutes later, Lexy Martin, 14, and Liz Gubser, 18, are back on the dry beach, showing their battle scars to fellow travelers from Missouri.

Though she's bleeding from coral cuts and a little shaken, Martin explains why she went into the water despite warnings against it: "All the people out here that aren't getting hurt look like they're having so much fun!"

And that's the dilemma of Sandy Beach, where, Goodwin says, "Tourists see little 10- and 12-year-old kids that have been doing this for some years and think they can do it, too." They can't.

Part of the lifeguards' job is to talk to people one-on-one and warn them of the beach's dangers. But sometimes there are so many people needing a wake-up call at once that it takes a megaphone message. On this day it's Dorr's turn.

"Attention on the beach: For those who are unfamiliar with this beach, it has the highest rate of broken backs and necks in the nation. This is not a beach for children or weak swimmers. There are safer beaches 10 minutes up the road. If you need information, come up and talk to us."

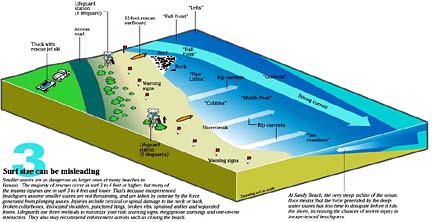

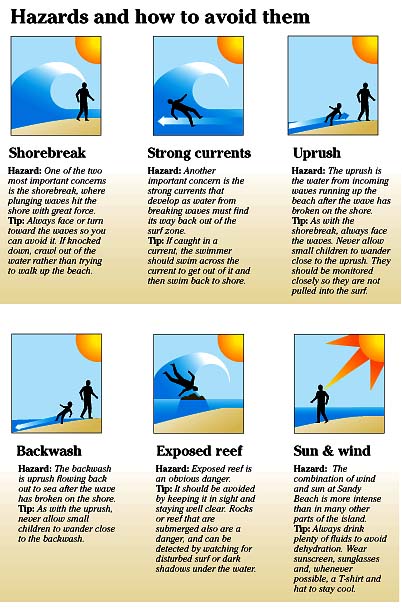

The warning signs are out there every day, permanent ones in the parking lot and mid-beach ones staked out in the sand: Dangerous shorebreak. Strong current.

"A lot of people don't look at it. They think it's a towel rack," Dorr says ruefully.

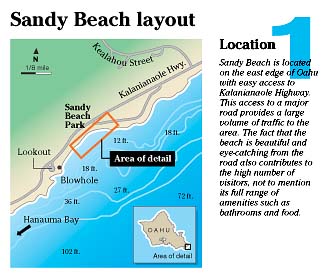

What makes this beach so challenging yet so popular? Water safety experts say three factors make the beach unique.

The afternoon sun shines through the breaking waves: the images of a half-dozen bodyboarders and bodysurfers are suspended in the blue-green water, like insects in amber.Then, POOOM!, the wave crashes to the beach and the lifeguards scan the foam for anyone who didn't get through it intact.

"The binoculars stay pretty much glued to our head," Dorr says. "You can tell a lot from somebody's expression."

What people think they know and what they actually know don't always jibe, the lifeguards say.

"The regulars help us out when we can't see things," Dorr says. "If they see a guy in trouble, they throw him on a bodyboard."

Suddenly, Dorr sees something. Like a flash, he's down the tower steps and running along the beach. He's joined by lifeguard Noa Spencer, who had been patrolling on the beach.

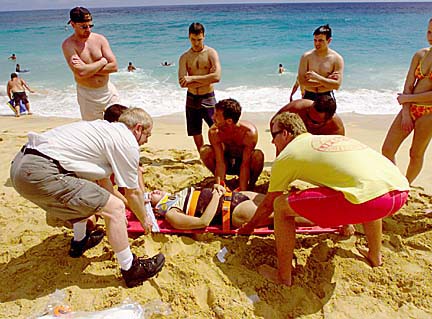

A young woman from Canada was knocked down by a wave in ankle-deep water and is lying on the beach, complaining of back pain.

As Dorr works to stabilize her neck with a cervical collar, Spencer asks her friends gathered around her: "Did you guys see the 'dangerous shorebreak' signs we have?"

The friends nod numbly, as Amy Autumn cries and whimpers. The lifeguards put her on a backboard, secure her head and ask her where it hurts."It hit her hard," says one of her companions. "She fell on the floor and she just rolled."

Ten minutes later she's in an ambulance, headed for Queen's hospital.

That's how quickly Sandy Beach can get you. "She said she was just going to take sand out of her bathing suit," says Spencer. "Never turn your back on the ocean."

It's not unusual that someone who's been warned gets hurt, says Howe. His advice to Ocean Safety's 180 lifeguards is "be professional. ... We're there to help. We do everything we can to advise people and give them good information, but we can't force people."

People know Sandy Beach's reputation and come anyway.

"The attraction is the power of the wave," said Clyde Hodges, 47, who bodysurfs Sandy Beach as often as possible. "When I think I've got it all together and want to experience powerlessness, I come here."