bout a month ago, surfer Christiaan Phleger of Honolulu went online to get a "clearer mental picture" of the waves on Oahu's North Shore.

Buoys that are monitored by the

University of Hawaii let Oahu

surfers check sets online

before heading outBy Lisa Asato

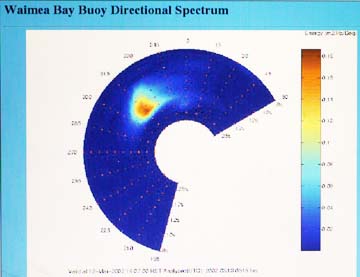

lasato@starbulletin.comHe didn't log on to a live video of pounding surf, but rather a color graph of wave heights and directions based on data tracked by a buoy two miles out at Waimea Bay.

"(The data) told me it was going to be about 3- to 5-feet local scale, which was a fun performance range for me," said Phleger, a surfer of 20 years. "It allowed me to choose a board that would be suitable for that size."

Since December the 500-pound, bright yellow buoy has been measuring data including wave height, swell direction and the length of time between waves, which is a factor in how large a wave will be when it breaks. The so-called wave summaries are updated every 30 minutes and appear at www.soest.hawaii.edu/~buoy.

Although the information has already proved useful for surfers like Phleger (he left his longboard at home that day in favor of his 6-foot, 7-inch high-performance board), it's too early to say for sure how geologists, biologists and others will benefit.

But University of Hawaii scientists are optimistic.

|

"It's a good field experiment, and everybody's very confident that it's going to yield some important data, but we still need to give it a few months to mature," said UH professor Charles Fletcher, whose research includes coastal geology.Jerome Aucan, an oceanography department research assistant who is handling the project as his doctoral thesis, said the buoy measures waves using three motion-sensitive pendulums. The 3-foot-wide buoy is also equipped with a global positioning system and a radio transmitter, which sends the data to a computer at the city Ocean Safety Division's North Shore Operations substation.

Aucan jokingly refers to the buoy as a "$40,000 toy," but he is also aware of its value.

"Once we have wave maps inside the bay, we can look at other kinds of things like coral reef growth, which depends on wave action," Aucan said, adding that the data have potential in understanding beach erosion as well.

The buoy, along with two others like it, were paid for by a grant from the federal Office of Naval Research. One buoy has been tracking similar data in Kailua Bay for the last 18 months. The other is a spare.

At Waimea the wave data are being coupled with an automated camera located in the tower of Sts. Peter & Paul Church, which records changes in the beach and shoreline as well as how far up the beach the waves run, Aucan said.

"If you want to know why or how beaches are changing, you have to know how waves affect that," said Mark Merrifield, assistant professor in the UH oceanography department and Aucan's adviser.

"We hope that eventually we'll be able to incorporate it into the operational wave reports, make it useful for the (National) Weather Service and the lifeguards," he added.

UH's Fletcher said it is rare to know where the sand goes when a beach erodes, but the buoy has documented a couple of wave events "where we think we're seeing some of the sand relocate itself offshore."

|

Fletcher emphasized that Waimea Bay is not eroding, but other North Shore beaches have experienced significant erosion stretching from years to decades, including Kawailoa Beach and portions of Sunset Beach."We often see them erode and don't know what causes them to erode," he said. "Studies like this can give us an idea of what is the cause of beach erosion. Without these sorts of data from the buoy, we just have to guess."

Capt. Bodo Van Der Leeden of the Ocean Safety Division said the Waimea data are a "good indicator of the type of surf hitting any North Shore beach."

Although the buoy is too close to shore to provide any type of advanced forecast or surf warning, Van Der Leeden said he is hopeful that it will be the starting point of new technology that could help lifeguards do their jobs.

So far, however, the data have been helpful at least in one area. "The local wave height judgment we've been making over the years and we make now, funny enough, Jerome has pretty much confirmed the heights that the lifeguards and local surfers are reporting for waves coming into the North Shore," he said. "(They) are actually pretty reflective of true heights."