|

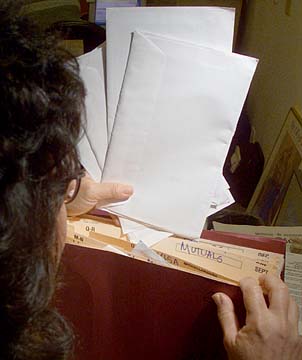

Bruised investors Every quarter since July, Pat Gee of Honolulu has neatly filed her mutual fund statements into an accordion folder and returned it to its proper place on the shelf.

hide the pain

When the market goes

down, down, down, some prefer

not to know how deep they areBy Dave Segal

dsegal@starbulletin.comThat wouldn't be unusual except for one thing -- she never opens the envelopes.

Gee, a divorced mother of one, is so afraid of bad news from her investments that she prefers not knowing anything at all.

For many, this is what it has come to in a 2-year-old bear market that only recently has shown signs of emerging from hibernation. Fear has replaced irrational exuberance.

Gee, a Star-Bulletin reporter who's in her 40s and considers herself a conservative investor, said she would rather wait for the stock market to improve before opening her statements again.

"I don't want to go through the roller-coaster ride of being devastated," she said. "(My portfolio) probably has been affected more than makes me comfortable but I don't want to know it for sure. If it recovers, then I would have felt bad for nothing."

|

While Gee might sound like someone in denial, she's not alone."I sometimes feel like (not opening statements) myself," said Peter Di Teresa, a senior mutual fund analyst for Chicago-based research firm Morningstar. "Sometimes the easiest way to stick with it is not to know much what's going on. Obviously, that's not a great policy overall because you do want to keep track of your investments and how they're doing. But my mother would be a case in point. My mother would rather not know."

With the 1990s bull market merely an afterthought now, one of the most sobering thoughts for today's shell-shocked investors is that money-market funds have fared better since the start of the millennium than the three major indexes.

The Dow Jones industrial average, which started 2000 at 11,497.12, closed Friday at 10,572.49 and is off 8 percent since that time even counting this past week's rally. The Standard & Poor's 500 index has fallen 20.8 percent to 1,164.31 from its 2000 opening price of 1,469.25. And the Nasdaq composite index has plummeted 52.6 percent to 1,929.67 from its millennium-opening price of 4,069.31.

By comparison, money-market funds have returned an average of just under 4 percent annually since the start of this decade, according to Denver-based Lipper Analytical Services.

Gee, who has put off contacting her broker for the past three years, grimaces at the idea that she would have been better off in a risk-free, money-market fund.

"I'm worried," said Gee, who is hoping to make enough in her IRA and regular accounts to support her during retirement. "But I keep hearing (from other people) the reassurance I got initially when I opened this account that this stuff is so diversified that it's supposed to cushion any big drop in the market.

"I started doubting this when I opened the first two quarter statements (of last year). The first one dropped, not a lot, but the second quarter dropped more than the first and it amounted to a little over $8,000 and that really scared me. So it can't be doing that well if (the market) got worse after that. ... If it goes below my original investment, I'll scream."

Off the track

Gordon Ching, president of the National Association of Investors Corp. Aloha Hawaii Chapter, said that even though he closely follows his portfolio, his sister in San Francisco might be typical of some of today's investors."I was just talking to her and asked her how she was doing in the market, and she said she doesn't follow it anymore," Ching said. "She used to track her portfolio quite closely. Where it used to be on a daily basis, it then became every other week, then once a month and then every other month.

"I think there's a lot of people out there who are just not paying attention because of a lack of interest. Before, they were making so much. But then they lost and some of them went into cash. People still put money in the market (such as through retirement plans) but don't track it every day like they used to."

Investors' denial may be part of a phenomenon called "learned helplessness," said University of Hawaii business professor Rob Robinson.

"It basically says that people get conditioned, or you can condition people, over time to feel that nothing they do makes any difference," Robinson said. "I think a lot of investors are feeling that way at the moment. They don't know whether they should sell, buy or get out of the market. At the same time, there's sort of a desperate clinging to hope. People hold onto stocks that don't really have any real good prospects for improvement. They don't want to sell them because they're hoping they'll eventually get back to what they paid for them."

Francis, a Honolulu senior citizen who didn't want his last name used, knows all about patience. Even though he was a toddler during the Great Depression of 1929, he's seen his share of bear markets since making his first investment more than 50 years ago.

"I'm staying the course," said Francis, a retired engineer who will be 76 in two months. "I really don't think (this market) is any worse than in the '60s. It's a down market, but so what? The stocks that I hold are all above what I paid for them."

Francis, who stopped adding to his own investments about 10 years ago, currently makes regular monthly payments into the accounts of his 16 grandchildren. For the most part, he has been sticking with blue-chip stocks like General Electric, IBM, Merck, Procter & Gamble, McDonald's, Intel and Microsoft. He also invested in one local stock, Bank of Hawaii parent Pacific Century Financial Corp.

Among his own holdings are such blue chips as Johnson & Johnson, Ford, Citigroup and one Hawaii-based stock, Hawaiian Electric Industries.

While it may feel like the bottom has dropped out of many investors' portfolios, Morningstar's Di Teresa said it is important for investors to look at their mutual funds or retirement plans in the context of how they are performing against their peers.

"If you have, say, a fund that focuses on large growth companies, in the past 12 months it may be down 15 percent," Di Teresa said. "But if you take a look at the typical large growth fund that's down 19 percent for the past 12 months, you're actually doing better than comparable types of funds.

"It's always important to make that apple-to-apple comparison. That can help ease the sting. You might say, 'My fund is not doing that well but it's better than most funds of its kind.' That increases your confidence for sticking with it."

Di Teresa admires the wherewithal that individual investors have shown in the face of diversity.

"A lot of investors have done a better job of sticking with it than we might have expected," he said. "I think prior to this bear market, a lot of talk from money managers and the media was that most investors have never seen a bear market and would turn tail and run if things turned ugly. That said, a lot of people clearly do feel like throwing in the towel."

However, Paul Loo, senior vice president of Morgan Stanley's Bishop Street brokerage, said investors would be wise to do just the opposite.

"My feeling is that there's a real super sale going on," Loo said. "The general rule of thumb is, the greater the sticker stock, the better they buy. Unless, of course, the investment is junk."

Ching said the range-bound stock market has caused him to alter his investing strategy.

"I'm taking my profits after a couple days and then wait until it settles back," he said. "It's not daytrading but it's taking what the market will give you."

Still, Ching hasn't lost sight of the buy-and-hold philosophy that NAIC espouses.

"The philosophy we teach at NAIC is that if you're not going to invest your money for three to five years, you shouldn't be in the market," he said. "We're going to have recessions like this."

Francis, who also has real estate investments, said that despite his age he has a long time horizon in the stock market because he's investing for his grandchildren now.

"(The stock) market doesn't bother me because I'm not looking at it like I'm going to be cashing something in during the next six months, or year, or next two years," he said. "Most of my grandchildren are young."

Still, despite the perseverance of many investors, Robinson believes the pain has been more widely felt than many have perceived.

"This downturn is more devastating to people than is commonly understood for a couple of reasons," Robinson said. "One, there's a whole generation that hasn't seen a down market. Second, even for the people who are older and heavily invested in mutual funds and 401(k) plans, the fact is the last time there was a down market they were not (fully) invested in mutual funds and 401(k) plans because those are relatively new phenomenons.

"For people now in their 40s and 50s, when they were in their 20s, they didn't have all their net worth in the stock market because they had company pensions, T-bills and cash. So this has affected probably the broadest segment of the population directly since the Great Depression. We have so many people in the stock market, relative to what was before, that I think people are shell-shocked."