![]()

Talk Story

Overpopulation threats

may be so much shibaiHAWAII'S population doubled in the 40 years between 1960 and 2000, from 632,772 to 1,211,537, according to the Census Bureau. In just one year, from July 2000 to July 2001, it grew by an estimated 1 percent -- 12,117 people.

The population of the United States is now 284.8 million. In 1960, it was 178.6 million. While Hawaii's population was doubling, the U.S. population as a whole grew "only" 62.7 percent.

My own Baby Boom generation is accustomed to such statistics. According to the United Nations Population Division, "Never before had the world's population grown so rapidly and for such a prolonged period as in second half of the twentieth century."

As recently as two years ago, the U.N. projected the world's population would soar from 6 billion today to 9.3 billion in 2050 and perhaps top out at 11.5 billion sometime in the distant future.

Such numbers raised concerns about overcrowding, depletion of natural resources, global warming and environmental catastrophe. Overpopulation has always loomed as an inevitable evil, dooming future generations to adopt the draconian policies of science fiction: sterilization, elimination of the elderly and undesirable, forced interplanetary emigration, etc.

Not so fast, Chicken Little. The sky is not falling after all.

A group of experts convened by the U.N. reported this month that world population growth will slow much faster than predicted and that it will actually start to decrease sometime this century.

We are increasingly aware that developed countries, such as Japan, Germany and Spain, have low fertility rates -- less than two children per couple -- while those in the developing world, such as Afghanistan, Zaire and Kenya, have rates as high as six or seven per couple.

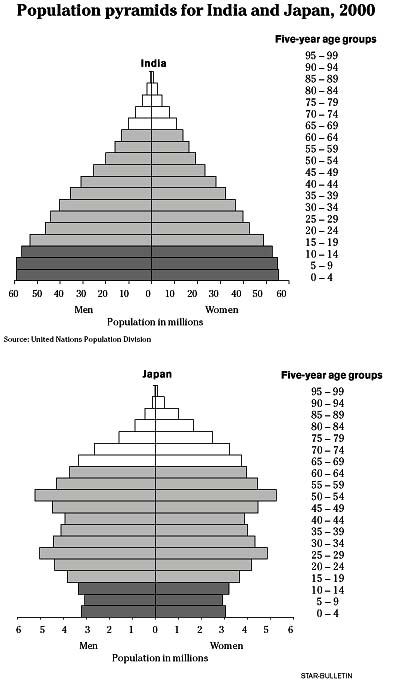

A recent East-West Center research paper compared "population pyramids" for India and Japan. These graphs stack bars indicating how many people fall into each five-year age group, from 0-4-year-olds on the bottom to 95-99-year-olds on top.

India's pyramid is almost a perfect triangle, with 115 million infants and toddlers on the bottom tapering to a couple of million oldsters on top. However, appropriately enough, Japan's is pagoda-shaped.

Instead of a triangle, it has large bulges where 11 million people fall into the 50-54 age group and 10 million in the 25-29 group. Meanwhile, the 0-4, 5-9 and 10-14 groups average a mere 6 million apiece.

What the U.N. experts termed "momentous" is that birth rates are falling faster than expected in some large countries that fall into the intermediate-fertility category, including India, Brazil, Pakistan, Indonesia, Mexico, Bangladesh, Egypt and the Philippines. As a result, the U.N. has lowered the projected fertility rate of less-developed countries from 2.1 to 1.85 children per couple.This "birth dearth," they now say, will offset ever-increasing life expectancies with "approximately 80 per cent of the world population ... projected to have below-replacement fertility before mid-century."

So, the population explosion will become a thing of the past sooner than expected. The world should max out at 8 or 9 billion people, not 11.5. In other words, about 25-30 percent fewer folks will be around when the global population peaks.

"Never before," the U.N. experts say, have "global reductions in the growth rate been achieved by the sustained and expanding reduction of fertility among the peoples of the world." Their new forecast puts to rest many doomsday scenarios, but it raises new concerns. The most immediate is coming to terms with aging populations.

As more national population pyramids increasingly look like pagodas, there will be more elderly over age 65 and many more retirees. Moreover, there will be fewer adult children who can provide financial support and personal care. Health care and social security systems will come under greater and greater stress.

"In 2000," the East-West Center noted, there were "nearly 12 people of working age in Asia for each person age 65 and above. In 2050, there will be only four, and in Japan, there will be less than two."

But the upside is that, unless new "baby boomlets" upset the applecart, a shrinking population will offer not just problems, but opportunities as well.

As Ben Wattenberg of the American Enterprise Institute noted in Monday's Wall Street Journal, "This doesn't mean we should pay less attention to family planning or environ- mental problems, but it does mean that those issues should be viewed calmly and without panic.

"The future remains a mystery, but inexorable population growth isn't part of it."

John Flanagan is the Star-Bulletin's contributing editor.

He can be reached at: jflanagan@starbulletin.com.