Fickle attraction The current attempt to consolidate Hawaiian and Aloha airlines is by no means the first.

Hawaiian and Aloha airlines

An Alaskan model?

have talked merger several times,

but never successfully

Name that airlineBy Russ Lynch

rlynch@starbulletin.comThe competitors have seriously discussed a merger three times, as far back as 1970 and again in 1988 and 1998, and there have been additional reports of one side or the other sending out feelers. All those attempts over the years failed.

Go back to 1964 and you see a suggestion from the Hawaiian Airlines president at the time, Arthur D. Lewis, who said a merger of the two airlines was "the only answer to local airline problems."

Always, the theme has been the same. Fighting head to head in the interisland market threatened to drive them both into bankruptcy.

There were always areas of disagreement, however, struggles of personality and power. Some of that came from inevitable conflicts between self-made post-war real estate millionaire Hung Wo Ching, who controlled Aloha, and John H. Magoon Jr., who represented old Hawaii land and power and was running Hawaiian.

|

Both Ching and Magoon felt that they had personally brought their airlines into the new jet age and, and while recognizing that there were good reasons to get together, they both harbored old resentments.The reason they have finally come close again now is an outside third party, Greg Brenneman and his TurnWorks investment business.

All the merger attempts, including the current one, set out to change one of the most colorful histories in U.S. aviation.

In October 1969, Magoon, then president of Hawaiian, said in a national travel trade paper that the financial problems of both airlines could force them together. Kenneth F.C. Char, then president of Aloha, came out with a fast and definite "not interested."

The idea took root, however, and in mid-January the airlines, both publicly held and reporting heavy losses, came out into the open and announced that they were working toward a deal. It would result in a new company, called Hawaiian-Aloha Airlines, with the former owners of Hawaiian holding 51 percent of the company and Aloha shareholders owning 49 percent.

Magoon would be president and chief executive officer, Char would be executive vice president and Ching, Aloha's chairman, would fill the same role in the new company.

Aloha had lost more than $2 million in 1968 and another $900,000 in the first quarter of 1969. Hawaiian lost $1.3 million in the first nine months of 1969.

|

They both had managed to raise fares twice in 1969 but it didn't help them much. (In later years a pattern would develop where one of them would post a higher interisland fare but the other wouldn't go along, forcing the first to cancel. That meant years of what Brenneman calls wingtip-to-wingtip flights with lightly loaded aircraft of both airlines flying the same routes at the same time, neither able to turn a profit.)At the time of the merger talks, air routes and the number of carriers flying them were strictly controlled by the Civil Aeronautics Board, which also provided subsidies for essential services where the airlines couldn't make a profit. The board, which went out of business with airline deregulation in 1978, was dragging its feet on subsidies for the two but sounded supportive of the merger.

On March 6, 1970, however, the airlines jointly announced that the talks were off because they had run into too many insurmountable obstacles, "technical and financial problems which created uncertainty with respect to the feasibility of the merger at the present time."

It was Hawaiian that abruptly called the talks off, but the airlines were trying again by July 1970. This time they held a news conference in the office of Gov. John A. Burns, who said he supported the merger.

As the Star-Bulletin's Shurei Hirozawa and Richard Borreca said in a story at the time, ongoing losses had "proved conclusively that while they don't like the idea of working together, the two lines simply can't go it alone financially."

Thirty years later, Brenneman's merger proxy statement has figures that indicate it is just as true today.

A Star-Bulletin editorial in 1970 called it a "shotgun marriage" but the extent to which each side needed the other probably would make it work.

In December of that year, shareholders of both carriers voted overwhelmingly in support of the merger, to create what was then being called Hawaiian/Aloha Airlines. Only one shareholder stood up to object at the Aloha meeting, one Samuel M. Slom, a minority shareholder with 28 shares, who said the merger would mean "the death of Aloha and the death of free enterprise in interisland air service."

Slom, now a state senator, said Friday that his view has not changed.

"I still feel exactly the same," he said.

Just as there is now, in 1970 there was public distrust of the idea that the skies would be controlled by a single airline, but Burns swore to use his considerable power to prevent monopolistic excesses.

In April 1971, the deal was unilaterally canceled by Hawaiian, apparently because Aloha's creditors would not subordinate their claims to those of Hawaiian's creditors.

So two airlines remained, still fighting for the same territory and both still losing money, with Aloha's Ching lambasting Hawaiian's Magoon in public for not telling the truth about why talks broke off, while Magoon declined to get into a war of words.

In early 1988 they were once again talking marriage. Both declined to comment at the time. Hawaiian was still losing money, showing red ink of nearly $9 million for 1987, but Aloha -- by now a private company owned by Ching and his partners -- said it was profitable.

The only public confirmation that they had been talking merger again came in announcements by both that had dropped their "very preliminary" merger talks. This time, it had been Aloha that sought to control the merged business.

According to the TurnWorks proxy statement issued earlier this month, Hawaiian and Aloha discussed a "potential business combination" in early 1998, but stopped talking in March of that year, before developing a definitive merger agreement.

Hawaiian talked later in 1998 to an outside airline, not named, that had expressed interest in acquiring Hawaiian, but that never went beyond preliminary feelers and "Hawaiian and Aloha continued to hold discussions about various ways to combine their operations" in 1998 and 1999 but all talks were ended in September 1999, the statement said.

Hawaiian has the advantage in history. It was not only the pioneer company in interisland aviation, it was a pioneer in aviation history in general.

Stanley C. Kennedy, son of the president of Inter-Island Steam Navigation Co., which had carried interisland freight and passengers since the late 1890s, flew airplanes for the United States in World War I. He came to the shipping company after the war, with wings and engines in his blood, and convinced the board to move into aviation as a way to improve interisland traffic.

According to Stan Cohen's book, "A Pictorial History of the Pioneer Carrier of the Pacific," produced for Hawaiian Airlines, the shipping company agreed with him and Hawaii's first commercial airline, Inter-Island Airways Ltd., was formed at the end of January 1929.

It wasn't until late 1929 that it started flying, and then only on short sight-seeing hops with a single-engine Bellanca monoplane, giving 10-minute rides for $5 a head.

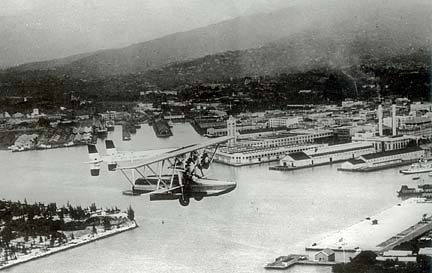

In October 1929, the fledgling airline got its first commercial aircraft, two Sikorsky S-38 amphibian planes that could, but never did, land on water and take off from a harbor. They carried a crew of two and eight passengers.

In 1941, the renamed Hawaiian Airlines started a new era with the Douglas DC-3, which had become a World War II workhorse. That brought Hawaii's first "stewardesses."

In July 1946, a new carrier appeared in Hawaii skies. Trans-Pacific Airlines, nicknamed "the aloha airlines," started charter flights, also using the DC-3.

Founded by entrepreneur Ruddy Tongg with some local buddies, it was elevated to scheduled interisland service in 1949 and it officially became Aloha Airlines in 1959, according to Bill Wood's book "50 Years of Aloha."

When jet service to the islands began in 1959, tourism took an entirely new tack and has been Hawaii's growth industry since.

Both airlines ended up with jet aircraft and later moved into long hauls. Hawaiian started Hawaii-mainland service in 1985 and was also flying South Pacific routes.

Aloha, which had some Western Pacific services, started mainland operations in early 2000.

Both have survived interisland competition -- Mahalo Air, which lasted about seven years and held down prices, and the short-lived Discovery Airways jets, driven out of the skies in a dispute over foreign ownership.

Proponents of the current merger say a monopoly is not a sure money-maker. Airline deregulation means any U.S. airline, as long as its safety and financial security can be demonstrated, can enter any U.S. market.

Any major U.S. carrier could enter the interisland market. So far, they have learned that it is better to partner with the locals.

BACK TO TOP

|

When Turnworks chief executive officer Greg Brenneman talks about his future vision for a merged Hawaiian and Aloha Airlines, one of the models of success he makes frequent reference to is Alaska Airlines. Alaska Airlines proves

to be tough model

for new carrierBy Lyn Danninger

ldanninger@starbulletin.com"Combining the airlines creates the opportunity to establish a financially strong Hawaii-based carrier to serve Hawaii similar to the way Alaska Airlines serves Alaska," Brenneman said Thursday in a release to Hawaiian Airlines employees that was also included in a newsletter to Aloha Airlines employees.

In some respects, Alaska Airlines shares much in common with Hawaii's two airlines. They all provide air service to a geographically isolated region, are long established in a home market and have enjoyed a loyal customer base for many years.

But there are differences. Hawaii's two airlines have suffered major financial losses over the past several years. But Alaska Airlines, while taking losses of $36.4 million in the fourth quarter of 2001, is already well on the way to a comeback -- likely sooner than some of its larger and stronger competitors, analysts predict.

The company also did not lay off any employees following the events of Sept. 11 and by Feb. 10 had re-instated all its routes.

"I think they could be back in the black in the second quarter (of 2002) and see decent profitably in the third quarter," said Seattle-based financial analyst Peter Jacobs of Wells Fargo Securities. "There will likely be a drop in the fourth quarter due to seasonality but the key is that they should be back to a full year of profitability in 2003."

The airline first began as McGee Airways in 1932, flying cargo between Anchorage and Bristol Bay, Alaska. McGee joined with other local operators to form Star Air Lines in 1937. The Seattle-based company eventually became Alaska Airlines in 1944, a year after buying three small airlines.

In 1985, it re-organized to form Alaska Air Group as its holding company and acquired a sister airline, Horizon Air, which flies to smaller destinations serving about 30 cities in the Pacific Northwest.

Today Alaska Airlines is among the 10 largest U.S. Airlines and serves 40 cities in Alaska and five other western states, Canada and Mexico flying out of hubs in Anchorage, Portland, Seattle and Los Angeles.

It will be adding two new routes, Seattle-Boston and Seattle-Denver, starting in April, said company spokesman Jack Walsh.

If there is a key to Alaska's continued success airline watchers seem to be fairly unanimous on what it is.

"The interesting thing about AK is that they have developed dominant market share to and from the state of Alaska but have done it over a long course of time by treating customers fairly and offering good service," Jacobs said.

He believes there are several reasons for the airline's comparatively quick recovery after Sept. 11.

Alaska had a strong financial position prior to the event, he said. Traffic also returned at a faster rate than most other major airlines, thanks in large part to its west coast location and concentration of routes in that region, he said. Around 30 percent of the airline's business involves travel within Alaska as well as travel to and from the state.

"They also held up fairly well just because of the necessity of air travel to move in and out of the state, so that helped insulate them," he said.

Jacobs doesn't undervalue the impact of Alaska's loyal customer base as a major contributor to its success.

Even after the 2000 crash of an Alaska Airlines MD-83 near Los Angeles, which killed 88 people, the public remained supportive of the airline, he said. The investigation into the cause of the crash is focusing on the horizontal stabilizer, a wing section that helps maintain level flight.

"After the (Alaska Flight) 261 accident, they came under a lot of scrutiny both from the FAA and the media," he said. "But when all the smoke cleared and there was no fire, the public had stayed with the airline through it all."

The company carefully evaluates a market before it makes a move, studying it to see what makes sense and what works best.

"Like Southwest they tend to have their own ideas and ways of doing things and these generally tend to be progressive. They also tend to be proactive and anticipate what is happening in their markets and act accordingly," said Greg Kahlstorf, president of Kahului, Maui-based commuter airline Pacific Wings.

If there is a way to describe Alaska's increasing growth and tactical approach to business it would be what company spokesman Walsh calls "The Seattle Strategy."

Subsidiaries: Alaska Airlines, Horizon Airlines Alaska Airlines Group

Ticker: ALK

Stock price: $30.30

Web site: alaskaair.com

Hubs: Anchorage, Alaska; Portland, Ore.; Los Angeles; Seattle

Headquarters: Seattle

Destinations: Alaska; Arizona; California; Colorado; Illinois; Nevada; Oregon; Washington; Washington, D.C; Idaho; Montana; Canada; Mexico

"We have what we call 'the Seattle strategy' -- a very strong base and hub with traffic coming down from Alaska and feeder traffic coming in from the northwest on Horizon. We also have a very loyal base in Seattle and feel that out of Seattle, we can go virtually anywhere," he said.

Still, the airline is not without its challenges.

Fares at major U.S. airlines were still 16 percent lower in January over the same time a year earlier, Bloomberg News reported, as airlines continued to slash prices to regain passenger traffic.

"There was an increase in traffic in January, the first one since Sept. 11, but there is still a long way as far as yields go," Walsh acknowledged. "Ticket prices are still very low."

But Walsh is optimistic about the airline's future, especially given its quick comeback.

"Losing money certainly isn't good, but comparative to others we are doing well, even though there is a ways to go."

It remains to be seen how closely Turnworks' Brenneman plans to emulate the successful Alaska Airlines model with the merged Aloha and Hawaiian airline.

With Hawaiian already flying 767s, airline watchers say extending the merged airline's reach beyond the West Coast would be a logical move. Brenneman has frequently said he aims to increase the number of mainland destinations.

"(The 767) can go well into the mainland, not only to the West Coast. Then why would you have a 767 if you didn't expect to make use of it?" Kahlstorf said. "There's no major airline based on the West Coast, not in the basin where they are going to serve. While there are big maintenance bases, there are no headquarters. I think it could be the path that he eventually will follow."

Inland cities in the West and Midwest could be likely eventual targets, Jacobs said.

"They may be able to do that to a couple of major cities like Chicago, Denver and Dallas," he said. "I would think they should be able to easily fill planes."

BACK TO TOP

|

The company organizing the merger of Hawaiian and Aloha airlines has refused to discuss the name of the new entity, so we thought it would be helpful to offer some ideas. To do that, we need to know what you think Hawaii's proposed flagship carrier should be called, and why. Entries must be faxed to 529-4792, e-mailed to business@starbulletin.com or mailed to 500 Ala Moana Blvd. #7-210, Honolulu, HI 96813 by Monday, March 4. Our staff will narrow the choices to five and offer those for a vote of our readers the following Sunday, March 10. One entry per person. All participants will be entered in a prize drawing. To be considered, all entries must include: Name that airline

Your name

Phone (day)

Phone (evening)

Suggested airline name

Why?

Entries may be printed without compensation. Judges' decisions are final. Employees of Oahu Publications are not eligible to participate.