|

Frozen Universe Hunting for meteorites on Antarctica's snow fields is no walk in the park, University of Hawaii geologist Linda Martel reports after a seven-week expedition with the Antarctic Search for Meteorites team.

A UH geologist finds adventure in a

7-week search for meteorites in AntarcticaBy Helen Altonn

haltonn@starbulletin.comShe had a pretty good idea what to expect from colleagues who have been to Antarctica. Still, there were surprises.

Driving Ski-doo snowmobiles -- the primary mode of transport -- was the most physically demanding part of the trip, she said.

|

"All of us have these muscles now, from gripping it with two hands for hours at a time," she said.Her knees were still sore for two weeks after coming home last month, she said, explaining they were always on their knees in the Ski-doos because they could see better.

An educational specialist in the Hawaii Institute of Geophysics and Planetology, Martel is sharing her "unique and fantastic adventure" with groups of schoolchildren. It was worth living in such an extreme environment to see their eyes light up, she said.

Even though she had seen pictures of Antarctica, the region's starkness was impressive to her.

"It is amazingly white and blue with distant mountains -- pretty in a black-and-white way. It is deprived of color somehow, no greens," she said.

The eight scientists, half of whom were meteorite specialists, spent an average of three weeks in the field, fanning out on parallel tracks and driving seven to eight miles from camp to an area called Meteorite Hills, she said.

“Even after 300 meteorites, it was an absolute thrill. Sometimes we would go half a day without seeing one. We had to cover lots of ground.” Linda Martel

University of Hawaii geologist

They spent the day doing systematic searches for meteorites, she said. "We were responsible for looking ahead, to the left and right, and as soon as we saw a meteorite, we would wave and all would come."

Ski-dooing was exhausting because ridge rocks deposited by the glacier littered the snow field, she said. "There could be meteorites, too. We had to do foot searches and walk through all these rocks, looking at every single one. It was arduous."

The group collected a total of 336 rocks, about average for the annual expedition, she said. "Maybe a dozen are different." An expert from Houston said he had never seen anything like one specimen, she said.

They used tongs to pick up the rocks and put them in a Teflon bag with white freezer tape for shipment. They will be analyzed by specialists at NASA's Johnson Space Center and the Smithsonian Institution.

Each one will be given a number so it can be tracked, Martel said.

"Even after 300 meteorites, it was an absolute thrill," she said. "Sometimes we would go half a day without seeing one. We had to cover lots of ground."

The temperature was minus 59 degrees Fahrenheit throughout the trip, which she expected, she said. "What I didn't expect was the wind chill."

There were three big windstorms with up to 100-mph gusts, she said. She said one researcher, in Antarctica for the 21st year, said he never experienced such strong winds there.

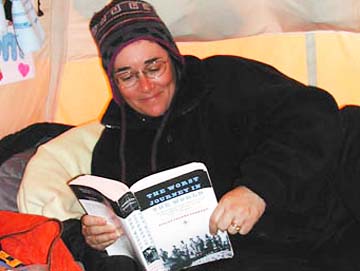

They had to stay in their tents some days because they could hardly stand and could not handle the Ski-doos, particularly in wind-driven snow. The longest continuous stay in her tent was three days, giving her time to read "The Worst Journey in the World," about the British explorer Robert Scott's ill-fated 1912 expedition to the South Pole.

She shared the dome tent with Nancy Chabot, a postdoctoral researcher from Case Western Reserve University.

Martel said the tent "never felt too small." In the middle was a stove, wooden boxes with food, and pots and pans so they could do their own cooking, she said. "The food was wonderful -- frozen steaks, salmon, shrimp and scallops."

Special boots and clothing protected the scientists from the bitter cold and fierce winds. Martel said she was covered with four layers, including a thick down-filled parka, making movements somewhat unwieldy.

|

She missed Christmas with her husband, Stephen, also a UH geologist, and their children, Owen, 14, and Leigh, 12, but they e-mailed her separately every day, she said. "The nicest thing they said was, 'Mom, this is not just your trip to Antarctica. This is family history now.'"The team members also had unlimited access to a satellite phone at $1.50 a minute. "We'll get a bill. It didn't seem too expensive to me at the time," she laughed.

Martel hesitates when asked if she would go back to Antarctica. Not right away, she said, but perhaps in the future because there is so much to see.

"It's a huge continent, and we were in one little place," she said. "I didn't see a single penguin."