Local Color![]()

Sunday, January 6, 2002

|

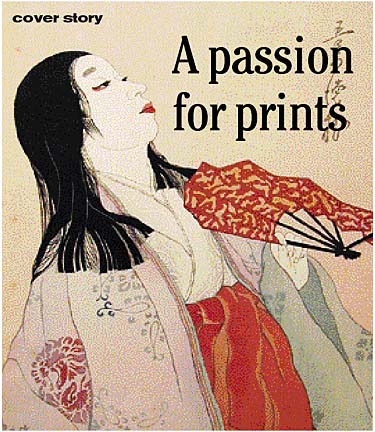

Philip Roach shares his 50-year

fascination with woodblock

artistry from Japan

Sparks didn't fly and bells didn't ring the first time Philip Roach Jr. laid eyes on a stack of original woodblock prints by the great Japanese artist Hiroshige. The prints, in broken, dusty frames, sat in the corner of an antiques store in New Orleans.

|

"I had gone there with a friend. I was just along for the ride; I didn't intend to buy anything. And then out of the corner of my eye, I saw them on the floor with dirt this thick," Roach said, gesturing to show the dust was at least an inch thick.Upon closer inspection, he realized the prints belonged to one of Japan's foremost woodblock print artists of the 19th century, known particularly for his landscapes. Still, Roach's heart did not skip a beat. He thought the art was nice enough, but it didn't move him.

of the Meiji, Taisho and Showa Eras from the Philip Henry Roach Jr. Collection Japanese Woodblock Prints

Place: Honolulu Academy of Arts, 900 S. Beretania St.

Time: 10 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Tuesdays through Saturdays, 1 to 5 p.m. Sundays. Prints from the late Meiji and Taisho periods open Thursday and run through Feb. 24; prints from the late Taisho and Showa periods open Feb. 27 and run through April 10.

Admission: $7; $4 for seniors, students and military; free to children under 12 and academy members; free first Wednesday of each month

Call: 532-8700

Roach bought them anyway, only because the then-young architect had trouble making architectural renderings. Roach couldn't master the Western perspective technique in which all objects recess toward a vanishing point. He thought the Japanese style of separating the picture plain into background, middle ground and foreground would provide a better model for his drawings.

Besides, the price was right -- $5 for the lot. The affair was not memorable enough for him to recall how many prints were involved. "Let's just say several, less than 10," he said.

|

Roach didn't realize the casual purchase would launch his 50-plus-year career as a noted collector of Japanese woodblock prints. His first collection, about 1,000 prints, was acquired by the Tokyo National Museum. His second collection, about 600 prints gathered since 1979, is donated to the Honolulu Academy of Arts, which is showing selected works in conjunction with prints from the famed James Michener collection.Japanese woodblock prints, which the Japanese refer to as "ukiyo-e," meaning "pictures of the floating world," date to the second half of the 17th century. The academy's concurrent exhibits, on display through April 10, focus on modern Japanese woodblock prints created since the 19th century. (See related story on Page G10 for the Michener collection.)

"The prints I fell in love with are from the modern period," Roach said, recalling his first encounter with vibrantly colored prints that immediately captured his heart and soul -- and pocketbook.

Several months after he bought the Hiroshige prints, a friend came by to tell him about some Japanese prints for sale. An American woman solider returning from Japan had put them on consignment in a frame shop, which was selling the prints for $5 each.

"Nobody wanted those prints. People either didn't know about Japanese prints or didn't care about them. I thought they were absolutely beautiful, just gorgeous and very different from the old prints," Roach said.

The modern prints were bolder in design and color, reflecting subtle Western influences but still very much in the Japanese artistic tradition, Roach said. The prints were inexpensive. Nevertheless, they were luxury items for the self-employed architect with a growing family.

"I couldn't really afford to buy them. Five dollars seems like not a lot of money, but back then it was money I needed to buy food for the kids. There were 55 prints, and I wanted them all. So I made arrangement to buy one a week for 55 weeks, and that's how my collecting really started," Roach said.

Roach made a point to become an informed collector, researching and gathering information on the artists and the craft. He learned, for example, that the production of woodblock prints is a team effort involving publishers and artisans with specialized skills ranging from carving the woodblocks to inking the prints. But the credit is always given to the artists, often someone with an established reputation, who makes drawings reproduced in prints.

Many prints were published in magazines and novels for popular consumption. The art form was considered common and frowned upon by the intelligentsia and upper class, who only considered paintings as worthy of collecting.

The prints were affordable, generally ranging from $10 to $35, when Roach was amassing his collection. He was not wealthy, but he made sure to set aside a little money to purchase prints. He traveled through the mainland, Japan and Europe in search of prints.

Soon Roach became known to the handful of dealers who imported prints from Japan. A San Francisco dealer later passed his name on to representatives from the Tokyo National Museum searching for prints for the museum's collection.

The quality of Roach's collection was such that the museum representatives, upon seeing his prints, made an immediate offer for his entire collection. The offer came at an opportune time when Roach decided to leave private practice and take a government job overseeing the facilities of American military exchanges in Europe. (He later took a similar post for the Pacific region, which brought him to Hawaii.)

|

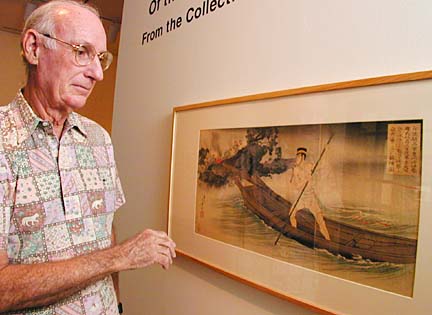

"I didn't know what to do with my prints anyway. I was glad that they went to some place like the museum, where people know what they are, can appreciate and take care of them," Roach said. (For sentimental reasons, he kept about 30 prints that began his collection.)He thought that was to be the end of his collecting, but old habits die hard. He began another collection after he visited one of his favorite galleries in London and saw a print of striking beauty.

"I simply couldn't resist; it was just gorgeous. I never collected to be collecting. There were always leaps of joy when I saw a good one, and I knew I was seeing a good one."

The print, of a Kabuki teacher striking a pose with a fan, is among the prints Roach donated to the academy and will be on display beginning Feb. 27. Roach's collection is divided into three rotations according to historical periods. The first rotation, prints from the Meiji period (1868-1911), concluded last week. The second, prints from the Meiji and Taisho periods (1912-1925), opens Thursday and continues through Feb. 24. The last rotation, prints from the late Taisho and Showa periods (1926-1988), runs from Feb. 27 through April 10.

Roach decided to donate his prints to the academy partly because he and his wife, Charlotte, wanted to downsize after their children left home. They moved from a 4,000-square-foot house to a townhouse measuring about 1,100 square feet.

"The prints really belong in a place where everybody can enjoy them," said Charlotte Roach, who shares her husband's enthusiasm for them.

The point of his collecting was not to satisfy his own vanity or for financial gain, Roach said. He sought the prints because he admired the artistic achievements of the artists and wanted to help perpetuate the tradition.

"I know there was not a high demand for these prints, but when I read (earlier in his collecting career) that the tradition of woodblock printing was a dying art, I knew I had to prove the author wrong," Roach said.

In the process of collecting, Roach also began compiling a reference book of woodblock artists. His book, nearly completed, lists 2,700 artists, including the 7,000 artists' names they used, variations in their signatures and other information.

Gardening Calendar

Suzanne Tswei's art column runs Sundays in Today.

You can write her at the Star-Bulletin,

500 Ala Moana, Suite 7-210, Honolulu, HI, 96813

or email stswei@starbulletin.com