Sunday, December 30, 2001

|

The wrath of an angry America that erupted after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11 has become the most far-reaching element in the foreign policy and security posture in the United States, especially toward Asia.

Both the attacks on Dec. 7, 1941,

and Sept. 11, 2001, changed

America's standing in the worldBy Richard Halloran

rhalloran@starbulletin.comThe surprise assault on the World Trade Center in New York and the Pentagon in Washington enraged Americans to an extent and a depth not seen since Dec. 7, 1941, when Japan mounted the attack on Pearl Harbor to bring the United States into World War II. The Korean War of 1950-53 was fought more with resignation than anger, the 25-year war in Vietnam divided the nation more than at any time since the Civil War, and the brief Gulf War of 1991 generated a detached, almost clinical reaction because it was won so quickly.

|

In themselves, the Dec. 7 and Sept. 11 episodes are quite different -- military targets on Dec. 7, civilian victims on Sept. 11; conventional military forces in the first, suicidal terrorists in the second; Pearl Harbor was 2,500 miles from the continental United States and Hawaii was then a territory; New York and Washington were the first assaults on mainland America since the British landed troops in the War of 1812; the death toll was 2,500 in Hawaii and about 4,000 on the East Coast.In common, however, was the surprise, the shock and the ensuing rage. In 1941, many Americans knew a war was coming but didn't know when or how it would start. In 2001, there were warning signs but most were not put together to predict the airplane hijackings that turned passenger planes into deadly missiles.

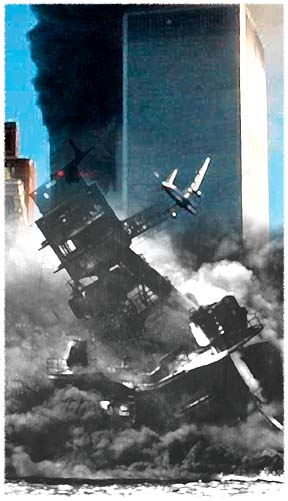

After each attack came a volcanic explosion. On Sept. 11, Americans' rage was fed by vivid television coverage, particularly when the fireball caused by the plane as it rammed into the World Trade Center was shown repeatedly across the country. That report was followed by nonstop coverage of the implosion of the twin towers, the assault on the Pentagon, the crash of a hijacked plane in Pennsylvania, and continuing reports on the heroic if mostly futile search-and-rescue efforts of the police, firemen and volunteers in New York and Washington.

|

Altogether, the events of Sept. 11 recalled a supposed lament from Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto of Japan after the attack on Pearl Harbor: "I fear we have done nothing but awaken a sleeping giant and filled him with a terrible resolve." Whether Yamamoto actually said that or it was a fanciful line from a Hollywood screenwriter for the movie, "Tora, Tora, Tora," matters little because the quote accurately reflected the admiral's thinking. He understood Americans, having studied at Harvard, served in the Japanese Embassy in Washington and played poker with the best of them.In an historically accurate vein, the historian Stephen Ambrose says that Dwight Eisenhower, later to command the invasion force at Normandy in 1944, wrote his brother, Milton: "Hitler should beware the fury of an aroused democracy."

How long this fury will be sustained is impossible to predict. Even so, much will depend on the manner the fury will be exploited by President Bush. As the first phase of the global campaign against terror wound down in Afghanistan, there was speculation about the next targets -- terrorists in the Philippines, Iraq, or North Korea or, perhaps later, those in the Middle East, North Africa and Latin America.

Whatever the eventual level of American fury, those engaged in the long-standing security issues of Asia -- the confrontations between China and Taiwan, North Korea and South Korea, India and Pakistan -- must consider the post-Sept. 11 attitude of the United States.

|

One change may be an Asian, especially Chinese, tendency to miscalculate the will of the Americans. Before Sept. 11, Chinese leaders repeatedly suggested that the United States had no stomach for using military power to protect its national interests in Asia. North Korean leaders may have been tempted to underestimate American resolve.The flights of B-1 and B-52 bombers over Afghanistan, not to mention the spray of cruise missiles or the bold insertion of Rangers and Marines into Taliban territory, should give pause to those who think the Americans have lost their nerve and no longer had the stomach for a fight.

Adm. Dennis C. Blair, who commands U.S. military forces in the Pacific, put it into context during an interview last fall: "When you look at the effect the terrorists wanted to have, they wanted some sort of Somalia-like effect. 'Americans die and the United States goes home.' I think what's happening is quite the reverse of that. 'Americans die and you messed with the wrong person.'"

In the fight against terror, President Bush laid down the fundamental objectives in a call to arms before the Congress on Sept. 20. "Our enemy is a radical network of terrorists," the president said, "and every government that supports them." The campaign "will not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped and defeated," he continued. "We will pursue nations that provide aid or safe haven to terrorism. Every nation, in every region, now has a decision to make. Either you are with us or you are with the terrorists. From this day forward, any nation that continues to harbor or support terrorism will be regarded by the United States as a hostile regime."

Derided by some Asians and Europeans for having a "cowboy" mentality, the president pushed on in Afghanistan and the rest of the world mostly fell silent. Those who sided openly with the United States were Britain, Japan, Canada, Australia, Germany, France and Italy. So did Pakistan, at considerable political and personal risk to President Pervez Musharraf. India did the same but that support was weakened by the continuing hostility between Islamabad and New Delhi.

By happenstance just after Sept. 11 came a document intended to be a fairly routine defense review that was suddenly propelled onto center stage. This was the awkwardly entitled Quadrennial Defense Review, or QDR, mandated by Congress to require the Pentagon to justify its military strategy, notably its requests for budget. This particular QDR was to have been the first set of marching orders from President Bush.

Then came Sept. 11. The QDR was hastily pulled back, heavily rewritten to incorporate what could be discerned of the new world order caused by terror, and published on Sept. 30. Freshly inserted were passages elevating homeland defense to top priority.

The review looked beyond Afghan- istan to a new strategy under which American military power would shift away from Europe and the Atlantic and toward Asia and the Pacific. Said Admiral Blair: "I think the most important thing that the QDR does is to give greater emphasis to Asia among the regions that are vital to the United States."

In Asia, the review said, the United States would seek no new bases over which an American flag would fly. Rather, the United States would forge what might be called "floating coalitions" in which the U.S. and Asian nations would band together to meet a contingency. In that case, the United States might seek access to the bases of a partner.

Military relations with allies would be cultivated through joint training exercises. The island of Okinawa in Japan would become more rather than less important, which meant that the running struggle among the Okinawans, the Japanese government and the U.S. military services would continue unabated.

The United States planned to make more use of Guam as a hub for operations. Three submarines will be based there within a year. Aircraft maintenance, fuel storage and ammunition depots will be enlarged. Bombers from the continental United States will rotate through Anderson Air Force Base more often.

To emphasize the shift in military power, U.S. aircraft carriers will spend more time in the Western Pacific, with the present six carriers in the Pacific supplemented by carriers from the Atlantic. A carrier from the Atlantic will patrol the Indian Ocean rather than the Mediterranean during a six-month deployment, freeing a carrier from the Pacific to patrol the Western Pacific and South China Sea.

In the unlikely event that stability comes to the Korean peninsula, U.S. forces there would shift from defending South Korea to a regional mission like that of the Marines on Okinawa. This reflects a change from a year ago, when American strategic thinkers were considering ways to reduce or even withdraw U.S. ground forces from Korea to free them for duty elsewhere.

Admiral Blair said: "You can imagine the future where, should tensions diminish on the Korean Peninsula, you'd not be on quite such a hair trigger as you are now, the forces in Korea would become more like the forces in Japan."

Richard Halloran is the

editorial director of the Star-Bulletin.