|

Pearl Harbor On Dec. 7, 1941, 19-year-old Taitsuke Maruyama donned his leather flight helmet, then tied on his hachimaki, a white cloth headband emblazoned with the red rising sun.

attack, as seen

from above

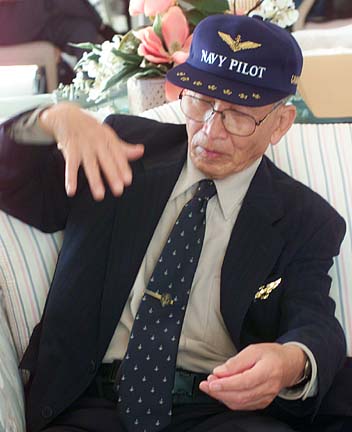

A Japanese pilot makes a visit to

the Dec. 7 memorial and brings with

him a unique perspective on the eventsBy Leila Fujimori

lfujimori@starbulletin.comUnderneath his uniform, the 19-year-old navigator wore a new undershirt and new underpants, knowing he was embarking on a grave mission, he said through an interpreter at the Ala Moana Hotel.

Maruyama climbed into the middle seat of the Kate torpedo bomber, which took off from the carrier Hiryu and launched a 1,600-pound torpedo that struck the USS Oklahoma in Pearl Harbor, he said.

Maruyama is one of three Japanese airmen who returned last week for the 60th anniversary of the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

Only 30 Japanese airmen of the 777 who flew in the attack remain; 56 were killed at Pearl Harbor.

His mission last week was to shake the hands of American Pearl Harbor survivors, some of whom he has met on his two previous trips to Hawaii.

"Yesterday's enemy is today's friend," he said.

|

Maruyama said both sides accomplished their missions, so there is no resentment against one other.On Dec. 7, 1941, when Maruyama's plane flew into Pearl Harbor, he could see the faces of Navy personnel on the deck of a cruiser docked at Ford Island.

"They looked up, wondering what was happening," he said.

The aircraft moved across Ford Island to its designated target, the USS Oklahoma, dropped low, and Maruyama released the single torpedo strapped to the plane's belly into the harbor waters 50 feet below.

When "a pillar of water appeared," the ensign knew he made a direct hit.

The aircraft carrier USS Oklahoma was hit by up to nine torpedoes, overturned and sank 20 minutes after the first hit.

Of the more than 400 on board the Oklahoma, only 32 sailors survived.

The crew, having accomplished its mission, flew back to the Hiryu.

Maruyama, who joined the Japanese Imperial Navy at 16, said he was fighting "for both emperor and country" and didn't know if he would survive.

"A soldier's duty is to accomplish his mission, so I was ready to die," said Maruyama, now 79.

He returned to a hero's welcome in Japan. But at the war's end, Maruyama said, "My head was empty."

After flying so many operations in the Pacific, he simply said, "It's finally finished."

Maruyama survived after missions in Australia, Ceylon, Santa Cruz Islands, where he torpedoed the carrier the USS Hornet, Guadalcanal and Midway, where he hit the carrier the USS Yorktown, which sank on June 6, 1942.

Val dive bomber pilot Zenji Abe was also in Honolulu for the Pearl Harbor observances.

He learned of the planned mission in April 1941 and took part in the Dec. 7 attack.

He said dive bombers would traditionally discover their targets from an altitude of 3,000 meters and dive to 800 meters to drop their bombs.

"However, the bombing accuracy was not satisfactory, so we reduced the attack altitude to 600 meters," Abe said. "Accuracy still was not satisfactory and eventually we lowered the attacking altitude to 400 meters."

The pilot and gunner/radioman who flew with Maruyama survived the Pearl Harbor attack but didn't survive the war. Maruyama said 80 percent of the pilots who flew in the attack were killed during the war.

"We're diminishing every day," said Jiro Yoshida, a Zero fighter pilot who flew at the end of the war and director of public relations for the Zero Fighter Pilots' Association.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.