[ PEARL HARBOR / FADING VOICES ]

|

The forgotten Utah In the still waters of Pearl Harbor's West Channel rests the rusty, half-sunken remains of the warship USS Utah, which was mistaken for an aircraft carrier by Japanese attack planes on Dec. 7, 1941.

Pearl Harbor veterans remember

a ship that entombs 54 sailors

-- and a girl's ashesBy Gregg K. Kakesako

gkakesako@starbulletin.comUnlike the USS Arizona Memorial, which straddles the sunken battleship and draws thousands of visitors each year, few people know the USS Utah Memorial exists. Access is restricted because it is on Ford Island, and visitors need military escorts.

|

The Utah is considered the forgotten memorial of the Japanese surprise attack -- although its decks are clearly visible above the waters off the north shore of Ford Island.In 1972 a concrete pier and a memorial slab were built and dedicated. The American flag is raised and lowered each day at the pier to honor 54 sailors still entombed in the ship. Also entombed are the ashes of Nancy Lynne Wagner, a baby who died in 1937. Her father -- Chief Yeoman Albert Thomas Dewitt Wagner, who survived the Dec. 7 attack -- had planned to bury the ashes at sea later that month.

Six officers and 52 sailors were killed on Dec. 7, either trapped inside the ship or as they swam to Ford Island. Only four bodies were recovered. Thirty officers and 431 sailors survived.

On the eve of the 60th anniversary of the attack, 10 Utah veterans and their families will make a pilgrimage to Ford Island to honor their shipmates. Among them will be Mary Kreigh, the surviving twin of Nancy Lynne.

|

After a bell-ringing ceremony, the survivors will throw orchids into the water, and a bagpiper will play as the flag is lowered at sunset.The Utah was first commissioned in 1911 as a battleship with a crew of 900. It was recommissioned in 1932 as a target ship and its decks were reinforced with timber.

Bill Hughes, 79, of Grand Prairie, Texas, was a radio operator aboard the Utah on Dec. 7. For this year's ceremonies, Hughes is making his first visit to Pearl Harbor and the islands in more than two decades.

Hughes, who acknowledges that he might have lied about his age to get into the service, said he had been aboard the Utah for more than a year when the Japanese attacked.

|

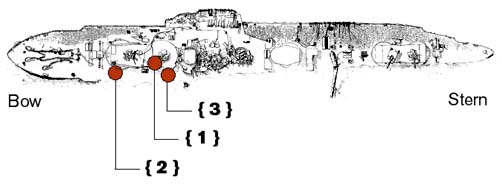

"Prior to Dec. 7, I had been promoted from sleeping on a hammock with one of the deck divisions to the more luxurious radio operator bunk room adjacent to main radio. We were located two decks below the main deck and one deck above the engine room."The first of three torpedoes that rammed into the Utah on that Sunday caught most of the crew, like Hughes, asleep.

"The tumultuous explosion that rocked the ship almost threw us out of our bunks," Hughes said. "We must have been looking at each other in sheer amazement."

Hughes said he recalled seeing only Radioman 3rd class Warren "Red" Upton dressed and "spiffed up" for a day ashore. "He was bending over someone's cot attempting to obtain an object from his locker."

Upton, 82, said he had the evening watch the night before and had gotten up early to go to Waikiki Beach.

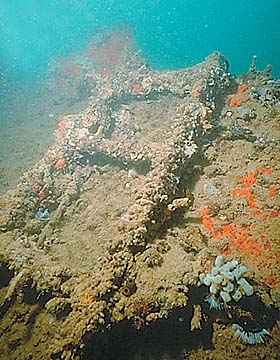

Exploring the Utah

|

"I was reaching over someone's cot to get my shaving gear out of my locker when the first terrific impact jarred the ship," Upton said. "No one below had any idea what it could be, but most of the men were soon awake and on their feet."When the second torpedo exploded 20 seconds later, Hughes said, the Utah began listing to port. "It was obvious to all of us that we needed to reach topside immediately."

As Hughes and Upton reached the main deck two flights up, some of his colleagues huddled for protection under a part of the ship's superstructure called the starboard castle, Hughes said.

"By this time Japanese aircraft were making strafing runs on hapless sailors who were exposed to their fire. Since all our guns were covered for bombing practice the week before, we could not fire back, and the giant ship was listing rapidly to port."

"We began to see the meatballs on the wings of the aircraft," Hughes added. "You didn't have to be hit by a 2-by-4 to know that we were being attacked. Then I got scared, terrified, shocked and angered, and mad -- all those emotions flowed through me at the same time."

Upton, who had been in the Navy for almost two years in 1941 after enlisting from the East Bay area in San Francisco, said his "main memory of that day was trying to get off the ship."

|

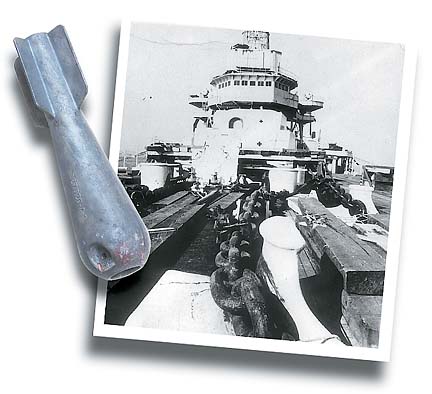

He said he slipped down the side of the Utah -- about 40 feet -- to the bilge keel. "I thought about jumping into the water below -- which seemed to be 60 or 70 feet below where I had stopped -- but there appeared to be too many men and too much debris below me."Hughes said there also was the danger of being crushed from falling timber. The Utah's decks had been covered with two layers of heavy timber, about 12 inches thick, so U.S. aircraft could drop practice bombs on the ship. On Dec. 7, Japanese attack pilots -- whose main targets were the carriers and battleships of the Pacific Fleet -- mistakenly torpedoed the Utah believing it was the carrier USS Lexington.

Hughes was able to swim to Ford Island. He recalled that "the only scratch I received during World War II occurred when wading up the beach onto Ford Island" -- a coral cut.

Upton, who had made it to one of the berth pilings, was picked up by a motor launch and taken to Ford Island.

From the cover of a sewer trench, the two sailors and other members of the crew watched the battle.

Upton said that when the Arizona was hit, "it exploded with such force that I thought for a moment the fuel tanks by Submarine Base had been hit."

Hughes would serve on several other warships, eventually ending up on the USS Gasconade, an attack transport that dropped anchor in Tokyo Bay on Sept. 2, just hours after the Japanese surrender.

Recalling his long trek from Pearl Harbor to Tokyo Bay that took three years, eight months and 25 days, Hughes said: "That long trip was paid for by many American lives as well as lives of our Allies and the Japanese. It is said that the military is only needed when diplomats fail. Let us hope we keep America militarily strong, the diplomats do not fail and this terrible history will never be repeated."

The National Park Service's Submerged Resources Center and the USS Arizona Memorial Association graciously provided the underwater images and artifacts, respectively, that appear throughout this special section. The Honolulu Star-Bulletin is grateful for their assistance. Special thanks