Sunday, December 2, 2001

|

Americans worship

at the altar of battle

Memorials provide an outlet

for veneration and worshipBy Burl Burlingame

Star-Bulletin

"Put off thy shoes from thy feet, for the place whereon thou standest is sacred ground." --(God's instructions to Moses, as the prophet stood before the burning bush in the wilderness.)

As Hawaii and the nation commemorate the 60th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor this week, with its inevitable, history-changing parallels to the surprise attack Sept. 11, the patriotic rhetoric will merit close attention.The themes will be worshipful. Shrines, hallowed ground, glory, final pilgrimages, sanctification, lasting memorials, purity of character, the battle against evil, veneration of ideals, sacrifice for the greater good, crusades, guardians of faith -- government and civic leaders will sound like pastors, preachers and prophets because it's the politic thing to do.

America was founded for secular reasons, unlike many other nations that draw their histories and borders from ancient kingly and tribal boundaries set in the dim reaches of prehistory by God himself. Or so their stories go.

The expansion of empires required belief in the moral rightness of conquest and for that, you needed God on your side. Even the communist empire, which eschewed religion as the "opiate of the masses," replaced religious fervor with the equally stratified catechism of the state, with priests as zampolit. God wasn't dead; God was red.

Although America was created from ideas, not beliefs, it was difficult to sift religious processes from the act of statecraft. We became "one nation under God" instead of "a nation under one God." We turned to the courts to separate church from state in school.

This is good. A nation that imposes a religious mandate upon its citizens is not a democracy.

On the other hand, it's impossible to divorce the process of religion -- the physical and psychological veneration -- from government. Government is supposed to take care of civilized society where individual citizens can't. We see beyond ourselves to the greater good, and both religion and government provide a framework and an ideological excuse for doing so.

In America, though we are blessed with natural wonders that seem touched by the hand of God, the idea of "sacred ground" is foreign, except to American Indians. Places like Jerusalem, Mecca, the Imperial Palace and Macchu Picchu are elsewhere.

The public need for ceremonial remembrance and redemption at the heart of organized religions runs deep. It's an inchoate need, hard-wired into our subconscious. It spills over into the worship of the American flag, which is treated with the reverence accorded religious icons in other cultures.

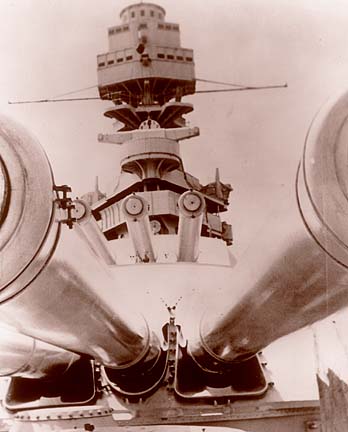

In America, we have created an altar of veneration that is state sanctified, nondenominational and cross-cultural -- the battlefield memorial. There Americans have been elevated by the cleansing spark of bloody sacrifice: Gettysburg, the Alamo, Little Big Horn, the Texas School Book Depository, Pearl Harbor, and in particular, the sunken USS Arizona, still holding the remains of those struck down by the terrible swift sword of another culture.

Everywhere are shrines that embrace the spiritual status of military fallen; Arlington, Punchbowl, the Memorial straddling the Arizona, the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier engraved: "Here rests in glory, an American soldier known but to God".

Monuments at such sites -- there are more than a thousand at Gettysburg -- "make it worthwhile to be a descendant," said Barrie Greenbie in "Spaces: Dimensions of the Human Landscape."

These sites have become popular shrines, hallowed ground, subject to endless near-theological debate on remembrance and sanctity. These are religious philosophies, not political, and strike citizens in their souls, not their brains.

Americans feel compelled to make pilgrimages to such sites. The two most popular in Hawaii are the National Cemetery at Punchbowl and the Arizona Memorial.

The rhetoric is religious iconography. They are shrines, sanctified by blood and sacrifice; they present war as a crusade against the forces of darkness; the fallen warrior is an emblem of cultural or moral failings as he dies for our sins, and lessons, or parables, are to be learned and passed on for the good of the nation.

Such institutionalized veneration is open to evolution and debate. The orthodox assert that changes to the sacred ground constitute a defilement; heretics argue that the site needs to be more inclusive, or up-to-date, or requires modern technology to preserve it. The pond, no matter how shallow, must be kept pure.

Writer David Chidester, in "Shots in the Streets," says sacred symbols are "directly related to the energy generated when people appropriate them, invest in them, and fight over them in the always contested struggles over ownership."

Who "owns" America's battlefield shrines, our temples to the military dead?

"Activities at these centers of power have helped to define, for numerous generations, those who are 'insiders' and 'outsiders' in American culture, those who belong in the stories and, equally important, how they belong in them," argues Edward Tabor Linenthal in his seminal work "Sacred Ground: Americans and their Battlefields."

"For insiders, or celebrants of patriotic faith, these power points are appropriate places of worship ... for outsiders, these places are the nerve centers at which they can begin the process of symbolically reshaping the nation's sense of the past, a process that outsiders believe can significantly alter their own marginal status."

America was created as a nation of outsiders. Cultural pluralism defines Americans, and that really annoys inflexible dogmatists like the Taliban. It will be interesting to watch the debates about the "proper" way to memorialize the heroic fallen in the World Trade Center, the day civilians and military became inseparably linked.

Looking back on Pearl Harbor, it's clear the Japanese never had a chance. Because of the vicious nature of their attack, striking down warriors in their bunks, our war against the Empire of the Sun took on the aspects of a crusade against heathen beliefs.

Because, after all, they struck on a Sunday morning.