Up close and personal It's not so much length, but girth. If sharks were long but narrow, we may not have nightmares about being swallowed whole. But sharks usually are not thin, and certainly not the 9-foot Galapagos variety I'm staring at a few inches from my face three miles off Haleiwa.

with Sharks

Underwater watchers are mostly

ignored as they view nature's eating

machines off HaleiwaBy Tim Ryan

tryan@starbulletin.com

"Curly" -- named for his damaged 18-inch dorsal fin -- looks pretty thick in his midsection. I'm imagining that with just a few bites, this eating machine could easily fit all of me in his belly.Fortunately, neither Curly nor a half-dozen of his smaller cousins seem interested in me or the other two occupants of a shark cage floating just below surface in 400 feet of water in Haleiwa Harbor.

No, they're focused on the occasional fish chunks being tossed by two men aboard the 24-foot Kailolo, where North Shore Shark Adventures was launched two months ago.

Owner Joe Pavsek reassured me before we headed out to the sharky site that the sharks we might see -- gray reef, Galapagos, sandbar, hammerhead and, "if we're lucky," a tiger shark -- are passive.

"We've had 12-foot sharks around the cage, and they're just not interested in people," he says. "The bigger they are, the friendlier, and they like being touched."

Yeah, right.Kailolo skipper Chris Lolley said sharks are "so smart" that if they don't recognize something as prey, they leave it alone.

"Sharks don't want to be injured and become part of the food chain; they always play it safe," he said, adding, "If you want to pet them, do it toward the back, the less pointy part."

As a surfer of nearly 40 years, I've held a deep respect and primordial fear of sharks. I once boasted, leaning toward the dramatic, that I'd rather be killed by a shark than hit by a car. I had second thoughts when I saw a curious contraption on Kailolo's stern.

"That's the shark cage," Pavsek said.

"But it's plastic?"

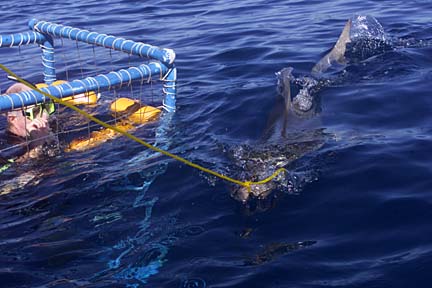

"Two-inch diameter PVC wrapped in 6-by-6-by-10-inch wire mesh held together with quarter-inch nylon rope," he says.

It was about 7 feet tall, 5 feet long and 4 feet wide.

"The sharks we see aren't aggressive, so this works fine," he assured.

"If you're worried about being attacked, don't," Lolley says. "That stuff really only happens in the movies."

It takes about 15 minutes to reach the dive spot, an area dotted with white buoys that mark where all metal crab traps have been lowered. Men on two boats use a motorized wench to retrieve their catches, dropping the old fish bait in the water, attracting sharks."We don't like to go to the same spot every time because the sharks get a little full," Pavsek says.

Within minutes the ocean surface is silently broken by the dorsal fins of two 6-foot Galapagos sharks. They're sleek, gray and quick, turning 180 degrees in a split second when bait hits the water.

Lolley steers our boat about 100 yards from the crab fishermen, and Pavsek asks who's going first as he pushes the device into the water.

Wearing snorkel and mask, I try unsuccessfully to enter the water with as little splashing as possible.While I wait for THEM to appear, I tell myself that the plastic cage is an important psychological barrier that makes THEM feel safe from me. Then I see the 4-foot-wide, 18-inch-high cage "window" that's big enough for a 6-foot shark to cruise through.

Several floats along the cage's open top keep it near the surface. Underwater visibility is about 75 feet.

Fifty feet below me, I spot two dusky images slowly rising; when I look to my left, I see a small shark sliding around the side of the boat; when I turn the other way, I see "Curly" for the first time, making a direct course toward the cage.

I push my back against the rear of the cage and feel the PVC bend slightly. I consider for a moment trying to scurry out and back into the boat. Before I make a decision, they're all around me.And guess what? They are curious, passing within a few feet, their black and yellow eyes watching me with nary a blink.

I'm in awe of these prehistoric creatures, their effortless swimming, their singular purpose: to find food.

Mark Gerasimenko, a Hawaii Kai underwater videographer, has made dozens of dives to photograph sharks. He tells me before my encounter that he never stays in the cages.

"These sharks are intent on getting the chum; they know what this food is, and they're not very territorial," he says.

Eye contact is the main deterrent, he advises. "It really changes the encounter. But remember you're a visitor in their element."

Pieces of fish float in and out of the cage. The sharks inspect it each time before swallowing. When I hold out a foot-long piece of fish flesh, they ignore it, refusing the free meal until I let it go.Then Pavsek tosses a large hunk of fish on the end of a rope alongside the cage. Curly is cautiously interested. He approaches from below, stretches his muscular body, then in a nanosecond springs forward, grabbing the entire chunk, thrashing the water with his tail fins.

The indigo ocean instantly is all frothy white when Curly stops moving. Just inches away is the non-"pointy part" of his body. I reach between the wire mesh to touch Curly where his body becomes tail. It's smooth in one direction, rough in the other, like a cat's tongue.

Suddenly, Curly turns, speeding by me, the bloody fish piece hanging from his mouth. Other sharks feed on the leftovers. I notice that a 5-footer has a hook stuck in his mouth.

When I'm ready to leave the cage, I decide to swim out the window to the boat rather than climb out the top to safety. I'm nervous and excited but unafraid.

I stop in the open ocean and turn around for a few seconds to see the sharks swimming by -- definitely not circling -- but their eyes seem to follow me back to the boat.

With North Shore Shark Adventures through AquaZone Dive Center, Outrigger Waikiki Hotel SHARK ENCOUNTERS

Where: Haleiwa Harbor

When: Two-hour tours offered between 7 a.m. and 3 p.m. daily

Call: 923-DIVE (3483); fax 922-0862; or North Shore Shark Adventures at 256-2769 or 637-9887

Cost: Viewing from the boat, $60; from shark cage, $120 (no scuba required, mask and snorkel provided)

Web site: www.AquaZone.net

Click for online

calendars and events.