Smoke and mirrors

"The Man Who Wasn't There"

Rated R

Consolidated Kahala; Signature Dole Cannery

1/2

It's worth mentioning the cigarettes at the outset, for they go far beyond mere props in movies like this. All the business of smoking -- the lighting, the holding, the dragging, the extinguishing -- is rendered in excruciating detail here. (It's a Nicorette junkie's nightmare.) Indeed, the filmmakers might easily have lopped off 30 minutes of this too-long saga by simply giving Crane (Billy Bob Thornton) a piece of gum from time to time.

But Wrigley's gum would no doubt have spoiled the atmosphere of claustrophobic existential loneliness so critical to the film's aims. (Never has smoking seemed less like a social lubricant than in "Man.") To be sure, Crane is trapped in a situation spiraling rapidly out of control, but he's also trapped in the labyrinth of his own mind, plagued by uncertainties that lead to all sorts of philosophical perambulation.

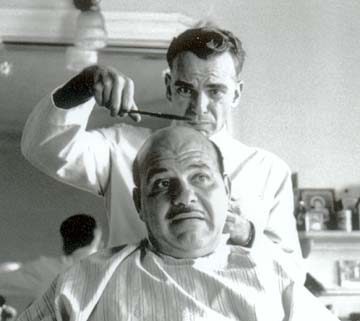

"Yeah, I worked in a barber shop," explains the man himself in voiceover, "but I never considered myself a barber. I don't talk much. I just cut the hair." (Making him a perfect candidate to go on a Coen brothers roller coaster ride.) Crane's laconic quality is engaging in a still-waters-run-deep sort of way. Still, it's no surprise when his restless wife Doris (wonderfully limned by Frances McDormand) is discovered to be having an affair with her boss, Big Dave (James Gandolfini).

Every man reacts uniquely to the news that he's a cuckold. Crane decides to go into a dry cleaning business. The year is 1949, so dry cleaning is purely a speculative venture, and in Crane's case one that will require 10 grand in seed money. This he tries to obtain by blackmailing Big Dave, sending him an anonymous note threatening to go public with knowledge of the illicit affair.

Of course, Big D pays up -- we wouldn't have a movie, otherwise -- and while it wouldn't be fair to go public with further details of the sinuous, dizzying plot the filmmakers have concocted, suffice it to say that Crane's fall from grace is never uninteresting. But the plotting takes a backseat, especially in the film's second half, to much meditation on epistemological issues, a choice that may well leave mainstream audiences running for the lobby.

Which is not to say that philosophical questions are asked with anything approaching rigor. When, say, a lawyer mentions the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle, the purpose is simply to sway a jury by convincing it that appearances can be deceiving. And by the end, once we're convinced that the world isn't what it seems to be, that it's populated with nothing but hucksters and cheats, the morally bankrupt but stylishly clothed, the cigarette-choked ... Well, you get the idea. The only safe strategy is to suspect the worst. It's a bleak vision, needless to say, but one that's thrown into sparkling relief by Roger Deakins' gorgeous black and white cinematography.