Civil trial greets Honolulu attorney John Rapp was at a loss when his expert witness refused to fly to Hawaii from Maine to testify in a medical malpractice lawsuit.

real-time video

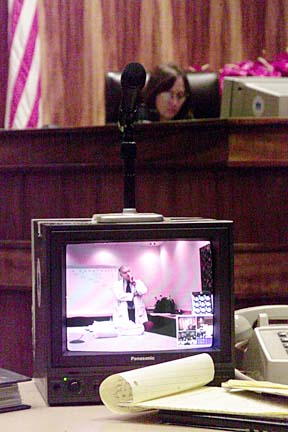

An expert witness testifies live on

camera in a malpractice caseBy Nelson Daranciang

ndaranciang@starbulletin.comThe trial had already started, but the witness refused to travel, citing his fear of additional terrorist attacks and the current dengue fever travel advisory for Hawaii.

When Rapp shared his predicament with state Circuit Judge Sabrina McKenna, she suggested getting the witness to testify via video conferencing. Some Hawaii law firms already conduct depositions by video conference, but none had used the technology in a trial.

One of the courtrooms in the state Circuit Court building in Honolulu is equipped with video conferencing equipment, though it had been used only to conduct arraignments in criminal cases from the Oahu Community Correctional Center and Halawa Correctional Facility. Still, it has the capability of connecting with similar video conferencing facilities anywhere in the world.

So Rapp contacted an audio visual company in Portland, Maine, and on Tuesday, Dr. William LaCombe became the first witness to testify in a trial of any kind in Hawaii by video conference, court officials said.

"Getting testimony in person is always better, but this worked," Rapp said.

Videotaped testimony has been used in other trials. LaCombe's is the first live testimony viewed by jurors on a video monitor.

None of the attorneys in the trial objected to the video conference testimony. Rapp's adversaries even were prepared to have their own expert witness testify in the same manner had the witness not appeared in person.

Attorneys see few if any legal issues in the use of video conferences for testimony in civil trials. The practice, however, raises constitutional questions in criminal cases.

"Criminal defendants have a constitutional right to confront witnesses. Normally it's face-to-face confrontation," said Gail Nakatani, state criminal administrative judge in Honolulu.

Nakatani conducts the video arraignments and her courtroom was used for LaCombe's testimony. She said arraignments do not involve witnesses. And being arraigned via video conference is voluntary.

An OCCC official said the video arraignment technology has been in place since 1996.

So far, there have been no requests to have witnesses testify by video conference in any criminal trials, Nakatani said.

In jurisdictions where requests have been made, there is no agreement on when video conferencing is allowed.

In 1995 a Florida court allowed victims in a Miami-Dade County robbery to testify against the accused via video conferencing from Argentina. The defendant was convicted. A state appeals court upheld the conviction.

In 1999 the 5th U.S. Court of Appeals reversed a trial court's decision to allow a defendant to be sentenced by video conference.

"I don't know if the issue has been settled," said Allen Williams, a Hawaii attorney who has researched the use of video conferencing in legal proceedings.

A case Williams handled six years ago was all set to be the first trial in Hawaii to include live testimony by video conferencing, but the parties settled before trial, he said.

Williams hired a private company which had its own video conferencing equipment because no state court had the technology at the time.

State Judiciary contractor Court Vision Communications handled the video conference in Hawaii for LaCombe's testimony. The company also handles video arraignments for the state on the Big Island. Headlight Audio Visual handled the video conference in Maine.

In 1997, Good News Jail and Prison Ministry set up a video conference for a hearing in a Kauai courtroom. A Hawaii inmate in a Minnesota prison did not want to return for his change-of-plea and sentencing.

The religious organization also sets up video conferencing twice a month on Oahu and once every three months on the neighbor islands for families of inmates on the mainland.