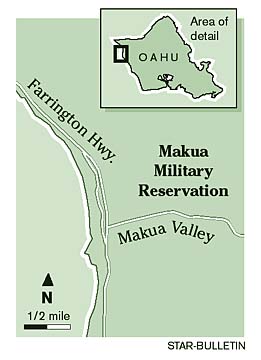

Army gets ready After three years and several environmental lawsuits, almost 100 soldiers will return to Makua Valley on Thursday to fire their weapons for the first time under a modified training plan that seeks to protect the valley's 53 cultural sites and 52 endangered plants and animals.

to train again

in Makua Valley

It will resume training in the

historic valley after settling a

lawsuit filed by EarthjusticeBy Gregg K. Kakesako

gkakesako@starbulletin.comThe modified training program limits the number of soldiers and the times and types of ammunitions that can be used in Makua Military Reservation. It was the result of an Oct. 4 settlement between the Army and the Earthjustice Legal Defense Fund, which had sued the Army on behalf of the Leeward Coast group Malama Makua.

Under terms of the settlement, the Army has three years to complete an environmental impact statement but will be allowed to use the valley while the document is being drafted.

The day after the settlement was announced, Col. Andrew Twomey, commander of the 25th Infantry Division's 2nd Brigade, met with leaders in his unit to lay out this week's training sequence.That meant a walk through the 1-mile training course as well as sessions on fire prevention, the cultural significance of Makua Valley, and the controls and restrictions now in effect.

The 2nd Brigade was selected to be the first to resume firing in the valley because it will be the first Schofield Barracks unit committed to combat if the 25th Infantry Division is deployed. It also is scheduled to go to Bosnia next year on a peacekeeping mission.

Only two of the brigade's nine companies have ever performed live-fire training, in Makua or anywhere else. The training tests the ability of a junior leader, generally a captain, to move his unit of nearly 150 soldiers to an objective while coordinating supporting fire from artillery and mortar units from neighboring hills and hovering helicopter gunships.

Twomey compared the scenario to a football team where the separate elements, such as the line and backfield, may practice separately but must train together before game day."It's bringing all these pieces together," Twomey said.

Yesterday, the Army took the news media on a tour of the 456-acre training area to show what is being done to protect Makua's endangered plants and animals and sensitive cultural sites.

Also in the valley were members of Malama Makua, who were photographing and recording the area's cultural resources before Thursday's exercise.

The Army said none of the valley's 53 cultural sites are in danger of being hit by Army bullets or artillery rounds.

Col. John Woods, the division's assistant commander in charge of operations, said the Army's mission is to train "under realistic conditions short of going to combat while still protecting the valley's cultural resources."

The Army has strung more than 5,000 feet of concertina wire to prevent soldiers from disturbing historical rock walls and other archeological sites. Small triangular red flags will warn soldiers to keep out of other areas.

Twomey said the flags provide the soldiers with realistic training since in Bosnia and other trouble spots of the world, red triangular flags mark the locations of minefields.

For smaller historical sites, such as areas that contain petroglyphs of humans and animals, sandbags will be used for protection.

Other areas will be marked as "no fire" zones on maps that units must use while training in the valley.

Twomey said all of the pop-up targets the soldiers will fire at are located down range and away from the line of fire of rifles, machine guns, mortars, artillery and helicopter gunships.

The Army also has spent $300,000 mowing 261 acres of grass in the impact area to prevent fire, since fire is the greatest enemy to Makua's endangered plants and animals and historical sites.

Also, whenever an exercise is held in the valley, the Army will station two firetrucks, a Black Hawk helicopter capable of lifting a 660-gallon fire bucket, five federal firefighters and a team of 20 soldiers.

Earthjustice attorney David Henkin noted that in September 1998, before live-fire training was halted, a mortar round started a fire that consumed 800 acres as it climbed up one side of the valley and came within 100 feet of known endangered plants.

"We continue to have concerns of the appropriateness of using Makua as a live-fire range, but we appreciate the Army's efforts," said Henkin, who will be spend this week in Makua ensuring that the Army lives up to the new settlement.