OHA scrambles to Deborah Lokalia Ho'ohuli remembers when former Circuit Judge Daniel Heely in 1996 ruled that the state had to pay the Office of Hawaiian Affairs additional revenue from other sources of ceded lands.

get back ceded

land revenues

A state high court ruling invalidating

state payments gives trustees

few collection optionsHistory of the ceded lands dispute

By Pat Omandam

pomandam@starbulletin.com

The decision, said the 27-year-old Waipio resident, gave the Hawaiian people a sense of hope in a time when little existed.

"My father's generation, and the generation before them, strived to create a more prosperous economy, environment and livelihood for my generation and those to come," Ho'ohuli said.

But, she said, that optimism has been dashed by the state Supreme Court's Sept. 12 ruling that invalidated the state law that allowed those revenue payments.

"Today, with the most recent ruling by the Hawaii Supreme Court, collective anxiety seems to be diminishing what little hope native Hawaiians of my generation have," Ho'ohuli said.

With a scheduled board leadership change on Tuesday, the next OHA chairperson is faced with organizing legislative support to restore the agency's stricken 20 percent share of revenue from public trust lands, a daunting task given Hawaii's economy is struggling and OHA's own existence is being challenged in court.

Already, Gov. Ben Cayetano said he will not hesitate to spend the millions of dollars earmarked as revenue payments to OHA.

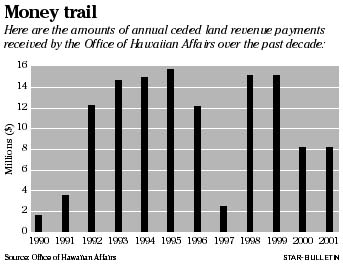

The governor said the 1990 state law, known as Act 304, "has no meaning now," and only if and when the state Legislature creates another law will such payments resume. Over the past decade, annual revenue payments to OHA ranged from a high of $15.7 million in 1995 to $8.2 million this fiscal year.

"We're going to be using that money, and we're going to use it now," Cayetano said after the Sept. 12 ruling.

The Legislature created Act 304 to more clearly define what amounts to 20 percent of the revenue from public trust lands, which are former crown and government lands, after a 1980 law was ruled too vague for the courts to decide.

Act 304, however, was ruled moot by the Hawaii justices' recent decision. The court, in deciding the state's appeal in the OHA vs. State of Hawaii case, agreed with Heely, who in 1996 ruled the state should pay OHA its pro rata share of revenue from five additional sources of ceded lands.

But the justices went further. They invalidated Act 304 because of its severability clause, which said the act would be moot if it conflicted with federal law. The High Court found the law conflicted with a 1997 federal law known as the "Forgiveness Act."

In September 1996, the U.S. Department of Transportation's inspector general found the state improperly made $28.2 million in ceded land payments made to OHA from the Hawaii Airport Revenue Fund. In April 1997, the department affirmed the decision and asked the state to repay that money.

Rather than take a hit in the state budget, Hawaii's congressional delegation, led by U.S. Sen. Daniel K. Inouye, pushed through a bill that "forgave" the state's debt to the Transportation Department. The law also banned the use of airport-related funds for nonairport uses, such as ceded land payments.

Inouye had said the federal law did not lessen the state's obligation to OHA, only that the money to pay OHA for the use of ceded lands under state airports must come from another source.

Meanwhile, the state had estimated the Heely decision could cost between $200 million and $1.2 billion, which it could not afford. As a result, negotiations between the state and OHA began but proved futile two years later.

OHA Chairwoman Haunani Apoliona, in a positive spin, said the High Court's decision affirmed the state's obligation to native Hawaiians. The agency, she said, will work with legislators to craft new legislation to address the revenue formula. Trustees were expected to meet with key lawmakers this week.

Meanwhile, trustees say a pivotal point in the 7-year-old ceded land dispute came on April 27, 1999, when the OHA board voted 5-3 to end negotiations with the state despite a settlement offer on the table.

At that time, trustee Clayton Hee, then OHA's top negotiator, and trustee Rowena Akana, then board chairwoman, had pushed to continue negotiations because there was progress and because the Legislature was poised to approve a settlement in the waning days of the 1999 session.

On March 31,1999, the state offered OHA $251.3 million and one-fifth of the state's ceded lands to end the dispute. OHA countered on April 1, 1999, with a $309.5 million offer. On April 16, 1999, OHA made its final offer to state negotiators to settle for $304.6 million and any lands, with a revenue stream of $7.4 million.

The state never responded to either of OHA's counteroffers.

Hee, in hindsight, said last week OHA should have taken the state's final offer as a "bird in the hand." If it did, OHA's native Hawaiian trust could be worth close to $1 billion today, and OHA would have a land trust about three times the size of Molokai and bigger than that of Kamehameha Schools.

Akana recalled she could not persuade a majority of trustees to continue the talks. Board politics, she said, got in the way of something phenomenal.

"The Supreme Court didn't want to make a decision," said Akana. "They kept holding out, hoping that we'd go to the table and try to figure something out with the state."

Former Circuit Judge Daniel Heely in 1996 ruled the state must pay OHA its pro rata share of ceded land revenue from these additional areas: Fund sources

>> Lease payments from duty-free concession agreements;

>> Revenues from Hilo Hospital's patient services;

>> Proceeds received by the Housing Finance & Development Corp. for projects on ceded lands;

>> Rental income received by the Hawaii Housing Authority for projects on ceded lands;

>> Interest on all these amounts.

But Apoliona said last week that a majority of trustees did not want to continue negotiations or settle the dispute because OHA's final offer contained troubling language that threatened future entitlements.

What many did not know, she said, was once the agency had received its share of ceded lands, OHA agreed to repeal Act 304, as well as Chapter 10 of the Hawaii Revised Statutes -- the very laws that created OHA.

Also, OHA offered to waive the agency's right to litigate on past breaches of the ceded land trust, she said.

"In essence, it extinguishes, it takes away the future of Hawaiians, and it is OHA trustees who are doing it," Apoliona said. "The fiduciary trust responsibility does not allow us to do that."

Apoliona recalled she and trustees Colette Machado, A. Frenchy DeSoto, Louis Hao and Mililani Trask opposed such conditions and did not like the way the negotiations were headed.

Instead, they voted on principle to end the talks and let the Hawaii Supreme Court decide its fate.

Deborah Lokalia Ho'ohuli said Hawaiians will need to be brave to overcome the high court's decision.

"That is what will be necessary for the people to prevail -- courage amongst the people -- enough courage to motivate the legislature, to remind them, 'Ua mau ke ea 'o ka 'aina i ka pono,'" she said, quoting the state motto, "The life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness."

Here's a chronological history of the ceded lands in modern Hawaii: History of the ceded lands dispute

1700: Pre-contact land in Hawaii had religious value to Hawaiians. Chiefs managed the land and granted use rights, but no one owned it.

1840: In an attempt to preserve the traditional land system, the Kingdom of Hawaii created a new constitution that declares that all the islands' lands belong to the chiefs and people in common, with the king as trustee.

1848: Kamehameha III divides land with 245 chiefs, with the king ending up with almost 2.5 million acres and the chiefs 1.5 million acres. Kamehameha III then divides his lands into two portions -- government and crown lands.

1893: Sugar, business and political interests combine to overthrow Queen Liliuokalani and establish a provisional government seeking annexation to the United States. A new Republic of Hawaii takes the King's and government lands, which together are called the public lands.

1896: Congress annexes Hawaii and President McKinley approves it. The republic "cedes" these public lands to the United States, which in turn directs revenues from lands not used by the military to benefit inhabitants of the islands.

1900: Congress passes the Organic Act, which sets up a territorial government with control of the public lands.

1959: Hawaii becomes the 50th state under the Admission Act. Most of the ceded lands are returned to the state, which must hold it as a public trust for five purposes, one being the betterment of conditions of native Hawaiians.

1978: Delegates create the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, which would get a share of the income and proceeds from the sale and use of the public lands. A 20 percent revenue formula is created as a resource for OHA by the state Legislature in 1980.

1983: OHA sues to get 20 percent of a settlement the state reached for an illegal sand-mining operation, and the next year sues to get its share from harbors, Honolulu Airport and other uses of the lands.

1987: The Hawaii Supreme Court responds to the lawsuit by saying uncertainties in the law make it a political question.

1990: Act 304 is created, which sets up a way to negotiate back payments on the ceded land revenue issue. After lengthy negotiations, OHA is paid $134 million in 1993 to cover the period of 1980-1991, but the agreement does not cover "several other matters" OHA claims it is due.

1994: OHA sues the state to get back payments from community hospitals, state affordable housing, duty-free concession leases as well as interest from these past-due revenues.

July 1996: Circuit Judge Daniel Heely rules in favor of OHA's motion. The state appeals, while estimates of the revenue in question range from $200 million to $1.2 billion.

May 1997: The Legislature creates Act 329, which attempts to resolve all ceded land claims through a committee while freezing OHA's ceded land payments at $15.1 million a year for two years. The makeup of the committee is challenged in court, and those efforts fail.

April 1998: The Hawaii Supreme Court hears the dispute and urges both sides to reach an out-of-court settlement. Talks sputter, and by year's end the high court warns the parties to settle or it will do it for them.

Also, Congress in 1998 passes what is known as the "Forgiveness Act," which excuses $28.2 million in payments the state made from the airport fund to OHA as ceded land revenue. Noteworthy is the federal law banning further use of airport-related money to pay claims related to ceded lands.

April 1999: Negotiations end after a split OHA board refuses to accept the state's last offer at $251.3 million.

February 2000: The U.S. Supreme Court rules against OHA in the Rice vs. Cayetano appeal of Big Island rancher Harold "Freddy" Rice, striking down the state's Hawaiians-only requirement to vote in the OHA election. The constitutionality of OHA is put into question.

March 2000: A group of Hawaii residents led by attorney William Burgess files a brief in Hawaii Supreme Court supporting the state's argument in the ceded lands dispute. The group says OHA is unconstitutional because of the Rice decision, the first of a handful of lawsuits filed this year challenging the agency's creation.

September 2001: The Hawaii Supreme Court decides Heely's decision was correct, but since Act 304 contained a severability clause saying it cannot conflict with any federal law, the justices ruled it invalid and mute. The High Court said it conflicts with the federal forgiveness act and says the state Legislature must come up with another formula to calculate revenue payments to OHA.

U.S. Public Law 103-150

OHA Ceded Lands Ruling

Rice vs. Cayetano

U.S. Supreme Court strikes OHA elections

Office of Hawaiian Affairs