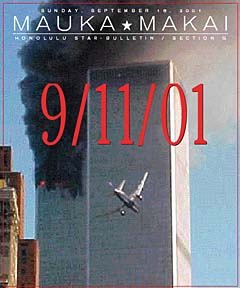

A generation’s A FAMILY VISITING Oahu from Connecticut is sitting beneath a banyan tree near Sans Souci beach, deep in conversation on this picture-perfect day.

defining moment

Terrorists and assassins shatter

the fragile innocence of childrenTim Ryan

tryan@starbulletin.comThe 10-year-old girl sits on what looks like a new bodyboard, her cheeks burnt from the sun, eyes red and glistening, her head down.

"I don't want to get on a plane again ever, not even to go home," she tells her father. "Daddy, can you promise me we'll be safe? I don't understand why this thing happened. It doesn't make sense. I'm afraid."

The parents are silent. Then the father speaks.

"I think I understand your feelings," Don Matthews tells Jolie, his daughter. "It doesn't make sense in a good world, but I suppose it did to the awful people responsible for this.

"America will survive this and we will be all right. We're safe, honey. Mom and Dad wouldn't do anything to put you, the family in danger, and our family will always be together to protect and care for one another."The child looks up as her mother, Marie, puts an arm around her.

"Jolie, when I was 11, President John Kennedy was assassinated, and he was such a good man, and I couldn't understand why anyone would want to hurt such a good person," she said. "Even when I read that it had something to do with his policies and politics, it didn't make sense.

"But some things never make sense because they're so awful. I remember that day like it was yesterday. It changed me almost overnight, the way I looked at life forever, honey. It was like I suddenly had to be an adult, and I wasn't ready."

As the nation reels from the attacks on the World Trade Center in New York and the Pentagon in Washington, D.C., children may be having the most difficult time understanding the horrific events and dealing with tremendous emotions of fear, helplessness and anger. It may be the first time kids have ever seen their parents and other adults so distraught and angry.

"It's a loss of innocence, a threshold event, something people, especially children, can remember for the rest of their lives," says Dr. Alberto Serrano, vice chairman of Child and Adolescent Psychology at the University of Hawaii's Department of Psychiatry. "Children are raised believing they're protected by their parents, their church, the police, friends and neighbors from all bad things."Then suddenly there's a wake-up call like this, and they're confused and quite fearful."

Baby boomers experienced many "loss of innocence" events: the assassinations of John and Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr., the Cuban missile crisis, the Bay of Pigs, the Vietnam and Persian Gulf wars, even musician John Lennon's death to a gunman.

"When terrible things like this occur, it not only leaves each and every adult shaken and mired in disbelief, it becomes impossible to completely shelter our children from the reality of what's happening," Serrano said.

For adults and children alike, the first response to an overwhelming disaster can be a sense of unreality. After the initial shock wears off and the facts sink in, then other emotions such as sadness, fear and anger are likely to emerge, Serrano said.

Al Takkon of Pearl City was 12 and living in Los Angeles when the Cuban missile crisis occurred in the early 1960s.

"I'm not sure I even really knew where Cuba was, and I certainly never thought anyone could scare the United States," he said. "But my mom was so scared, she had me and my brother pack clothes in case we had to evacuate the city.

"I remember asking her what evacuate meant; then, where would we sleep, would I be able to listen to Dodger baseball games."

Takkon, a retired Lockheed aircraft worker, said his mother called a family friend who had an underground bomb shelter in his back yard to ask if they could go there in case of a nuclear attack.

"I knew what an atomic bomb was, and I thought about having no place to hide from it," Takkon said. "I felt completely helpless and remember crying off and on for days.

"I even kept a knife under my pillow for a while in case some enemy broke into our apartment."

While adults struggle to understand the awful events of the past few days, Serrano said it is important that parents understand children's perspectives and help them cope.

"Even though we're angry and upset about the U.S. not being as safe as we would like it to be, parents must offer their children some security in their world," he said.

"I was never the same naive, baseball-loving kid after that missile crisis," Takkon said. "I was embarrassed, but my brother and I slept in the same bed with my mom for a few weeks. We told her it was so we could protect her, but I'm sure she knew we were just scared."

How do you explain to a child why good people die when they see constant and repeated images of it in magazines, television, films and on the Internet?

"Today's kids get more doses of terrorism and acts of violence than at any time in history," Serrano said. "They see things just minutes after they happen, or in this case as it happened, over and over and over again. Adults get overloaded by it all."

A quartet of teenagers -- two boys and two girls -- were standing near See's Candy in Kahala Mall looking at the fiery images of the World Trade Center on the Star-Bulletin's front page.

"Unreal," said Glenn, 16, a Kalani High School student (none would give their last names because they were supposed to be in class). "How would you get out if you were on the top floors?"

"No way. You're talking death, brah, and painful."

Stacy, another Kalani student, turned away.

"This is so scary. It's like no one's safe," she said. "I'm never going to New York. My parents have friends who got mugged there."Kim says she is not likely to travel anywhere soon.

"I'm never leaving Oahu," she says. "It could happen on an interisland flight. People take hostages here, even."

Richard says his father was so upset the morning of the attack that he thought he might have a heart attack.

"He was just marching around the house with his fists clenched and crying and yelling," the youth said. "I've never, ever seen him like that, even when I stayed out all night this summer or my sister got hit by a car. I had to calm him down. It made it worse for me, for sure."

The teenagers agreed they would always remember Sept. 11.

"I never thought all the prime-time shows would be interrupted," Chad said. "Even 'Friends' wasn't on."

Fear of the immediate future was in all their minds.

"My dad said something awful is going to happen to the people who did this to America and that they deserve whatever they get. He said America is angry and we all will have to make sacrifices.

"I hope it's over before I can get drafted. I don't want to kill anyone."

At Kaimuki's Big City Diner, Margie Hayashi was having breakfast with two friends the day after the attack.

"It makes me so mad, I couldn't talk to anyone -- not my husband, my kids or their kids," she said. "I was sure I would scream at them or something."

Hayashi, 50, remembers when President Kennedy was killed and her father "ranted and raved" around the house, screaming at family members, yelling we should attack Russia and Cuba.

"I thought he was mad at me, too," she said, laughing about it now. "I remember he wouldn't look any of us in the eyes, and he punched the wall. I thought if I said anything, he would spank me for something."

Serrano said children as young as 6 are developed enough to understand the awfulness of what has happened and of being helpless to do anything about it or similar incidents in the future.

The worst thing a parent can do is "stay panicky," Serrano said. "We model for our children; they watch our reactions and react to us. If we look fearful, they will react in kind.

"From a very early age, children are acutely aware of the emotional state of their parents. It's fine to let your children know that you're upset and sad, but make it clear that you're not upset with them, and try to be as calm and reassuring as possible."

There are several steps parents can take to comfort their children and help them make some sense of the tragedy, Serrano said.

>> Offer reassurance to make sure your child knows that those closest to him or her are all right and that the immediate family is safe. This is important even if you do not live near the attacks, because media coverage seems to make everything seem closer.

>> Try to maintain the daily routine, which gives children a sense of structure and security.

>> Do not overdo watching the news on television, even though you may need to catch each unfolding event. If your children do watch the news, sit with them to explain what is happening and answer their questions.

>> It is also important to let your child know that people in authority such as the president, firemen, police and teachers are making sure everyone is going to be safe.

>> Reassure your child that the bad events happened in very few, specific places.

Serrano says it is important to watch your children for signs of stress like fear, nightmares, depression and mood changes. Handle it with understanding and patience.

Some children's reactions will be easy to interpret. They will repeatedly blow up buildings make of blocks or crash a toy airplane. They will draw explosions and smoke, as they saw on television. Other reactions will be less obvious. Children may behave more seriously, with less spontaneity or joy, or look in a worried way at the sky or buildings along the street, as though they might burst into flames. Other children may be unusually wild or disobedient.

Children's artwork may be indirectly related to the traumatic events. A child may draw a sad-looking house, for example, or a dog that is sick. Another child might make a happy scene with a sun and flowers, declaring, "I want everyone to feel happy again."

John Dora of Hawaii Kai said the seminal event of his youth was John Lennon's murder in 1980.

"I had gone through the terrible political assassinations, but I kissed it off to politics," he said outside Hawaii Kai's Costco. "But I couldn't rationalize why someone would shoot a Beatle, a musician, someone who only brought joy and happiness to the world, certainly my world," said Dora, 45.

"It's cliché, I suppose, but it was the day the music died. I sort of gave up on people and was afraid of believing in a lot of things for a long time."

He laughs.

"Males have trouble with commitment and intimacy anyway, and John Lennon's senseless death just made me want to retreat more."

Serrano emphasized that it is important for adults and parents to pay attention to their own levels of stress and shock.

"No matter the severity of this event, your child's world still goes on, and as a parent you need to maintain a structure in their life and provide a sense of security," Serrano said. "You are the rock for them."

Takkon remembers that soon after the missile crisis was over, "or seemed over," he, his brother and their mother started listening nightly to L.A. Dodger baseball games together and play cards.

"It actually made us closer, and I felt safe that things may happen but then they get resolved," Takkon said.

He understood that his mother was upset, but she reassured him that she was not angry at him or his brother.

"I remember her saying to me she would always make sure we were safe," he said.

Some children, like Jolie, personalize events by thinking about an airplane trip they just took or are about to take, or a tall building they visited, Serrano said.

"It's understandable," he said. "Even young, school-age children begin to understand that if a bad thing happened to someone else, it could happen to them, too. Try to make your children feel as far removed from the tragedies as possible."

Jolie's point of reference about the seriousness of the tragedy was that "even all the Disneylands are closed."

"Why would anyone want to hurt Disneyland?" she asked her parents.

Serrano said parents in Hawaii can simply and honestly reassure their children that these recent events happened far away from their homes, and "that should make them feel better," Serrano said.

There is an even simpler solution, he said.

"Simply tell your children that you love them, that you will protect them and that grown-ups are making sure that nothing else bad will happen," he said. "Often that's enough to put a child's mind at ease."

Star-Bulletin reader Brandi-Ann Tanaka believes the written word has the power to heal and unite people. A poem of healing

She put her feelings into verse and encourages others to do so as a personal form of therapy.

"My idea is to have both kids and adults express their feelings and emotions through poetry, short stories and anecdotes in your features section, as a reaction to what has happened."

If it takes one tragedy to find

Then one terror will proceed

Because life goes on each day

Without people who believeIf it takes one miracle to provide

Love and generosity

Then the path will lead the way

To hope and camaraderieBeneath the darkest of nights

And underneath the crumble of earth

A light too tiny to find

Shines at every birthA beginning for you and me

To look at the hate we hide

Buried beneath

It grows in anger insideBut if we dig in deep

And we love today

It grows with hope

and shines the wayFor in every tunnel

And seemingly tragic end

There's always a chance

For the world to mendIt's times like these

That continue to remind

To love every day

Be thankful and kindSo one day soon

Tragedies will die

Not the innocent

Wasted livesPlease join me today

To hold every man's hand

And remember the vain

That corrupts each man

Click for online

calendars and events.