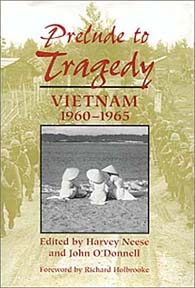

A valuable Vietnam WHEN THE LONG nightmare of the Vietnam war was finally over, Americans did not want to think about it or read about it and only a few were able to write about it.

remembrance

BOOKSHELF

Review by Richard Halloran

rhalloran@starbulletin.comThen the late Harry Summers, an Army colonel, broke the silence with a book in 1983 entitled "On Strategy: A Critical Analysis of the Vietnam War," an incisive inquiry into why the United States had failed in that far off Southeast Asian country.

From then on, Americans have been deeply introspective about what went wrong and why. Books have come from the pens of generals and politicians, from dog-face soldiers and Marine grunts, from scholars and journalists, from critics and apologists. A quick look at the Amazon booksellers Web site shows 4,640 works in print with the word Vietnam in the title.

Among recent works is this collection of essays by five Americans and three Vietnamese about the early days of the war. Like most collections, it is uneven but has nuggets of value, especially from the Vietnamese, whose views are little seen by Americans.The book actually covers a longer period, the date in the title being misleading. The American involvement in Vietnam began just after the North Vietnamese defeated the French at Dien Bien Phu in May 1954, part of which is covered in these essays. This reviewer served in Vietnam as a lieutenant of infantry in 1955.

A better subtitle, moreover, might have been: "If only they had listened to me." Rufus Phillips, the leadoff contributor, was a member of the Central Intelligence Agency's team led by the flamboyant, opinionated and controversial Col. Edward Lansdale of the U.S. Air Force.

"There seemed to be willful ignorance and an almost boundless arrogance of the part of too much of America's leadership," Phillips asserts. Maybe so, but the Lansdale team was equally guilty of ignorance and arrogance in those early days, particularly in thinking that what had worked in the Philippines would work in Vietnam. Lansdale had helped Ramon Magsaysay, the defense minister of the Philippines, to defeat the Communist Hukbalahap insurgents, which vaulted him into the presidency of his nation. Lansdale then moved on to Vietnam, where he sought to help Ngo Dinh Diem defeat another insurgency by applying the lessons of the Philippines.

The analogy was flawed. Magsaysay was an energetic, gregarious man who got out among the people to persuade them to follow him; Diem was a reserved mandarin who wore a white linen suit on his rare appearances in public. In culture and history, the Filipinos and Vietnamese have almost nothing in common. The communist threat to the island Philippines was easier to contain than that in continental Vietnam, where support to the insurgents came overland from North Vietnam and China.

Hoang Lac, who was a general in the South Vietnamese army, agrees with Phillips about the ignorance of American leaders. Of Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, Lac says: "He confused himself while conducting the war. He did not understand the North Vietnamese communists, he did not understand South Vietnam, he did not know what should be done, and finally, he did not even know how to effectively use his forces."

Tran Ngoc Chau, who joined the communist Viet Minh in the mid-1940s to undermine the Japanese occupation and then the returning French rule of Vietnam, and later served in the South Vietnamese army, faulted his own government and the United States for ignoring the people of rural Vietnam.

"Neither Diem nor most of his American advisers had much respect for rural South Vietnam and the people who lived there," he writes. "It was his and the Americans' greatest miscalculation."

Harvey Neese, a specialist in agriculture and animal husbandry who served as an adviser in Vietnam for six years, sums up a theme of this book: "It is sad to say that few, if any, of us were ever consulted by high-level American officials on our viewpoints about what was happening in the rural areas of South Vietnam before the decision to escalate the conflict was made."

"This tragic decision, to introduce American combat troops and to militarize and to Americanize the conflict, led to America's first and only loss of a war in its history."

Click for online

calendars and events.