New tsunami The last of six deep-ocean instruments to alert the tsunami warning network to an approaching deadly wave is being installed this month.

warning system

in place

Deep-water sensors on buoys

will provide more data on wavesOcean landslide set off Hilo tsunami, scientist says

By Helen Altonn

haltonn@starbulletin.com"It is the biggest advance we've had probably in the last 30 years in terms of sea-level instrumentation," said Chip McCreery, director of the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center at Ewa Beach.

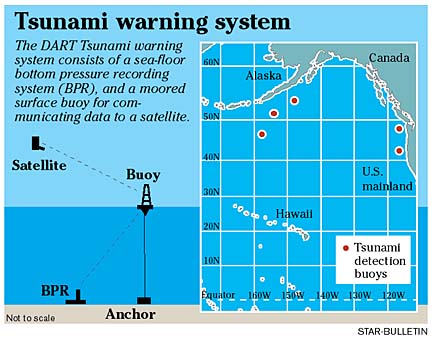

The ocean bottom sensors send data to satellites via buoys. Three are located off the Aleutian Islands in Alaska, and two off Oregon and Washington. The sixth is going in near the equator "along a path to give us readings of tsunamis from South America -- a dangerous zone for us," McCreery said.

He added the buoy system is working "excellently" after some initial problems.

Normally, the deep-ocean instruments do not produce much data. But if there are any unusual signals, they go into an emergency mode and transmit data every few minutes at higher sampling rates, McCreery said.

"Our software that monitors this will detect emergency transmissions and immediately put something up on the screen," he said, noting this happened several times when earthquakes triggered seismic waves.McCreery said the buoy system presents two big advantages over some 100 sea-level sensors scattered around the Pacific to measure the height of tsunami waves. The sensors are usually in a bay or harbor or on a pier, and there is no land to put them on in the North Pacific, he said.

When a tsunami is traveling through the deep ocean and approaches shallow water where it is recorded, the waves get modified in complex ways, McCreery said. "So it is very difficult for us to look at those readings and know what is actually going on in deep water and coming toward Hawaii or any other shoreline.

"The buoys overcome those difficulties. We can place them strategically wherever we want them in the ocean." They also provide a true reading of what is in the deep water, so the information can be compared with numerical models to lead eventually to some forecasts, he said.

A long-term goal is to reduce the number of warnings for nondestructive tsunamis, which are costly and a big inconvenience, McCreery said.

The buoy system was among advances reported at recent meetings in Seattle of federal and state officials and scientists concerned with protecting Pacific islanders and West Coast residents from tsunamis.

They reviewed a five-year National Tsunami Hazard Mitigation program, a partnership between five Pacific states and federal agencies.

Their goal is to establish tsunami mitigation plans, evacuation route signs and procedures for communities in Hawaii, California, Oregon, Washington and Alaska.

Attending from Hawaii besides McCreery were Mike Blackford, International Tsunami Information Center director; Brian Yanagi, Hawaii State Civil Defense Earthquake and Tsunami program manager; and, from the University of Hawaii, geophysicist Gerard Fryer, physical oceanographer Doug Luther and Michelle Teng, assistant professor in civil engineering.

About $2.3 million per year is going into the tsunami program on a national level, McCreery said.

Hawaii was the only state with evacuation maps, so a lot of effort is going into producing similar maps for at-risk areas of the other states, McCreery said.

Hawaii has been a national leader in preparation and warnings for tsunamis, McCreery said, "because we are so much more aware of the threat, and our Civil Defense is a lot more up to speed on this stuff than other communities."

The scientists also would like to produce a warning where they could say a tsunami is expected but the highest run-up on shore, for example, will be 10 feet. In the 1946, 1957 and 1960 tsunamis, he said, run-ups were more than 33 feet.

It is hoped to begin in the next few years, but it may take some time to test the forecasts and use them with confidence since destructive tsunamis do not happen often, McCreery said.

"Even with everything that we have, when we have a tsunami, even with gauges, we're only getting a few little spot measurements of what this thing is as it is moving across the Pacific, and we have very little time to deal with it," he pointed out.

"It's not like a hurricane where you have satellite photos days in advance and can send planes out to get measurements inside a storm."

A lot of interesting things are going on, such as numerical modeling to try and explain what happens in a locally generated tsunami, McCreery said.

Rather than depend on historical data, he said, "We're starting to see a little more modeling work that can be applied to problems of warning centers."

University of Hawaii geophysicist Gerard Fryer, trying to figure out the cause of the devastating April 1, 1946, tsunami, said he is building a case that it was generated by a submarine landslide shaken loose by an earthquake. Ocean landslide set off

Hilo tsunami, scientist saysBy Helen Altonn

haltonn@starbulletin.comThe puzzling tsunami killed 159 people in Hawaii, smashed the Marquesas Islands and went on to Antarctica.

A recurrent theme among scientists and engineers at a recent International Symposium on tsunamis in Seattle was that "landslides are not something we can ignore," Fryer said.

He cited the 1998 tsunami in Papua New Guinea that killed more than 2,000 people.

There is still some controversy about it, but most scientists believe the waves were triggered by a giant submarine slump minutes after an earthquake, he said.

The people lived on a spit of land only about 16 feet high, and the waves were about 33 feet high, he said. They washed over the entire spit and beyond, he said, adding that about 75 percent of the people were killed in several villages.

"There is this realization that collapse slips and landslides have to be considered (as tsunami sources)," Fryer said. "A big one almost certainly will follow an earthquake, but it can happen spontaneously as well."The 1946 tsunami was very strange, Fryer said. "We don't know how big it was. I'm arguing that a landslide was so large that it was responsible for what was recorded on seismographs."

A recent earthquake in the Pacific Northwest "reminded us there is a tsunami hazard there," Fryer said, "and in fact, the outer banks of Washington state in many ways are very much like Papua New Guinea, with sand spits and lagoons behind. There is no easy way off the spit in a hurry. It's scary, but things can be done about it."

Resort complexes, big hotels and condos could provide refuge, he said. He also said that both Oregon and Washington are good about public education.

Fryer is working with Dan Walker, former Oahu Civil Defense tsunami adviser, to try to figure out a sensible warning system for local tsunamis.

Walker is putting 10 or 12 gauges on the Big Island to detect tsunami waves traveling inland. They would trigger an alarm instantly at the Tsunami Warning Center if waves wash over them and they are flooded.

At the symposium, Fryer talked about avoiding false alarms and panic evacuations with Denis Mileti, noted University of Colorado social scientist and Natural Hazards Center director.

He said Mileti, who is on the tsunami hazard review committee for the National Tsunami Hazard Mitigation program, told him not to worry about false warnings.

Mileti said there has never been a panic evacuation in any emergency situation in the United States.

"People in general are too level-headed," Mileti told Fryer. "They don't run around waving their arms and screaming. They're more interested in saving lives."