Dig that sinkhole MAHAULEPU, Kauai >> A day at the beach for the Burney family of New York, which has spent every summer vacation since 1996 at sun-drenched Mahaulepu, a spectacular coastline adjacent to the posh Poipu resort district:

The Burney family helps plumb

the depths of a Kauai fossil siteBy Anthony Sommer

tsommer@starbulletin.comDavid Burney stands in ankle-deep water, seven feet down in a dark hole, cutting into thick mud with a mattock and pulling loose a large stone.

"These rocks are very sharp. They were torn off the coast and thrown in here by a tsunami about 400 years ago," says Burney, a paleoecologist from Fordham University.

Nearby, his son Alec, 12, is collecting tiny bone fragments given to him by volunteers sifting through mud brought up from the hole.

"These are bird bones," he explains. He picks up a tiny piece and says, "This could be part of a bird's skull, couldn't it?"

Alec's mother, Lida Pigott Burney, who specializes in the study of microscopic fossils, sorts through the tiny pieces."These were all broken up by the tsunami," she says. "In another day or so we'll be below that zone and finding entire skeletons."

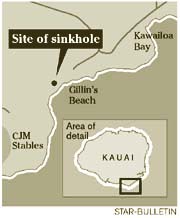

The Burneys are at the bottom of a huge sinkhole only a few hundred yards from bikini-clad vacationers working on their tans, totally unaware that the most important paleontology excavation in Hawaii is within shouting distance.

Although the way to find the Mahaulepu sinkhole is mentioned in several tour books, it isn't obvious to the casual passer-by. Reaching the top of it requires climbing a very steep hill. Entrance to the floor of the sinkhole involves a hike on a narrow jungle trail and crawling on hands and knees through a small hole in the rock.

Burney himself discovered it quite by accident in 1992. He was visiting friends who had found fossils of extinct birds nearby and was wandering the area looking for other promising sites when he happened on some tourists who told him about the entrance to the sinkhole. Fellow scientists said they knew of the sinkhole, but doubted there was anything there because the floor was covered with a deep layer of red clay.

"The clay is from the 20th Century, mostly created by runoff from agriculture," Burney said. "I pushed a 2-inch core sampler through the clay into a layer of prehistoric peat and brought up the skull of an extinct endemic Hawaiian coot. I thought if I could make a find like that with one two-inch hole, there must be much more here."It wasn't until 1996 that he found time to explore the sinkhole further on a federal grant. Pila Kikuchi, professor emeritus of archaeology at Kauai Community College and Kikuchi's wife Dolly have been his constant collaborators. Hundreds of people ranging from school children to tourists have provided volunteer labor.

There are many fossils to be found in Hawaii, but most are, as Burney calls them, "snapshots" -- a few specimens from a specific point in time.

The Mahaulepu sinkhole is unique because it is in one of the few areas of rock anywhere in Hawaii that isn't volcanic. It is literally a vertical time tunnel through relatively soft layers of limestone.

Mahaulepu was once a sand dune area, very much like the current Barking Sands and Polihale State Park on the west tip of Kauai, Burney explains. The sand is mostly ground up coral skeletons with a high calcium content. Over the centuries, the right -- and very rare in Hawaii -- combination of acid from plant life and moisture turned the sand to limestone. Water draining from the nearby mountains bored through the limestone, creating a giant cave.

About 7,000 years ago, a portion of the cave roof collapsed, creating the sinkhole. The fallen rock blocked the flow of fresh water to the sea and a large lake formed, surrounded by sheer cliffs.

For thousands of years the unique bird life that evolved in Hawaii lived on or near the lake. Polynesians probably hunted there frequently before European contact. Their tools and weapons have been found in the mud.

Today, the sinkhole resembles more a small canyon in northern Arizona or southern Utah than any place in Hawaii: A vertical wall ranging in height from 25 to 80 feet rings the flat clay floor. Giant plum trees grow at the bottom of the hole. And only a short distance away Grove Farm is mining limestone for use in cement manufacturing.The clay floor is about 20-feet thick but the water table that once was the lake is just below the ground surface. Portable gasoline-powered pumps are used to suck water away from the digging. One area has been excavated down to the limestone and that hole now is being expanded, first horizontally and then vertically, layer by layer.

Evidence found so far shows arrival of the Polynesians resulted in some very dramatic changes in the untouched islands. Bones of pigs brought by the Polynesians begin appearing and the bones of flightless birds begin disappearing, indicating they were slowly hunted to extinction. Burney attributes the gradual disappearance of certain plants and land snails to the Pacific rat, which arrived with the Polynesians.

While he is not ready to pick a date when the Polynesians first arrived, Burney says the indications are it is not as far back in time as some studies suggest.

The arrival of Europeans was even more dramatic and their impact on the land more profound. European explorers in the late 1700s and early 1800s left behind goats as a gift to Kauai King Kaumualii. The goats ravaged the defenseless endemic plant life. "We can see when Captain Cook arrived by the appearance of goat bones," Burney says.

The Burneys so far have discovered the remains of 45 species of birds, about half of them extinct, and 14 species of extinct land snails. The fossil bones are shipped back to Fordham University for study and ultimately will be stored at the Smithsonian Institution. Artifacts of Polynesian settlement such as tools are being stored at Kauai Community College.

Some day, the Burneys hope to build a museum to display their findings, but right now their efforts are concentrated on digging and sorting. Meanwhile, the excavation will be the topic of a segment of an eight-part series on extinction to be shown on the Public Broadcasting System beginning in late September.