NEWELL, Calif. >> Squat and desolate, the old jail lies silent under a lowering sky, desert winds whistling through gouged-out windows. Japanese internees, kin

work for camp memorialBy Michelle Locke

Associated PressInside, scrawled on a cell wall chalky and fragile as a butterfly's wing, an old grievance: "MAMORU Yoshimoto 5/24/45 ... 180 days."

This is almost all that remains of the Tule Lake Segregation Center, a remote outpost on the California-Oregon border reserved for a little-known group of World War II activists: Japanese Americans who dared to speak out against internment.

Today, the camp that once held 18,000 people has all but vanished from the sagebrush steppe. The barracks were sold off long ago to area farmers for $1 apiece. The miles of barbed wire and gun towers are gone.

For years the camp has been largely ignored, an embarrassment to the government that sent thousands of people into unearned exile, as well as to Japanese Americans who quietly accepted internment.

Some want to change that.

The Tule Lake Committee, made up of internees and their children, is working to create a permanent memorial to the people who lived and died here.

"It's like the untold story of Japanese America," says committee member Barbara Takei. "It's a story of Japanese-American resistance."

An alien landscape

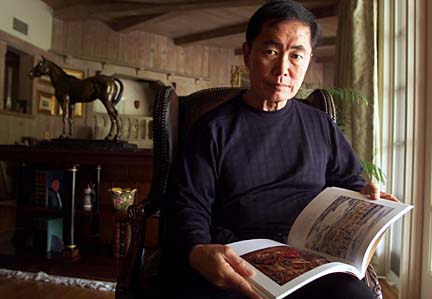

George Takei was 6 when he first laid eyes on Tule Lake."When we got there it was tumbleweeds rolling around, blown by the wind, and the ground was sandy and gritty and sharp," recalls Takei, who would grow up to portray Mr. Sulu on television's "Star Trek." "My childhood recollection is of no vegetation."

The Takei family, no relation to Barbara Takei, had already spent two years in an Arkansas internment camp before they were sent to Tule Lake. They were among the 120,000 Japanese Americans, many of them second-generation Americans, forced from their homes by order of President Franklin Roosevelt in the aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Tule Lake, one of 10 major internment camps, was set on Bureau of Reclamation land about 350 miles northeast of San Francisco. It was transformed into a segregation center in 1943 after internees were asked two key questions: Would you be willing to serve in the U.S. Army? Would you forswear loyalty to the Japanese emperor?

Nearly half of those at Tule Lake replied "no" or refused to answer; eventually other naysayers, or "No-No boys," were sent there from all over the country.

Their reasons for the refusal varied. Some said they would not serve in the Army unless their constitutional rights were returned. Others objected to the assumption that they would be loyal to Japan. For first-generation Japanese, known as issei, answering yes meant becoming stateless, since discriminatory laws had prevented them from getting U.S. citizenship even though they had lived in the United States for years and their American-born children, nisei, were citizens.

Takei's father was among those who answered "no" in protest.

"My father was denied naturalized citizenship in the country of his choice; he was stripped of his property and home and business; he was incarcerated, and he said, 'I am not going to grovel before this government,'" says Takei.

Camp attitudes ran the gamut. A small group of internees were militantly pro-Japan; others had not answered "no" but stayed at Tule Lake because they could not face being uprooted again.

There was a riot over fears that food was being siphoned away from the camp; an internee was shot for being too close to the fence; at one point martial law was declared.

Meanwhile, some Japanese Americans from Tule Lake and other camps who answered "yes-yes" were making their own statement, fighting in the 100th Infantry Battalion and 442nd Regimental Combat Team. The units, later combined, were made up mostly of Japanese Americans and were among the bravest in U.S. military history, receiving more than 18,000 honors.

Post-war finger-pointing

After the war, some Japanese-American veterans ostracized the No-No boys."The tragedy is that this group vilified, pilloried the resisters, and many of them suffered incredibly after the war," says Takei. "Both groups are, in my mind, heroes. The real villain here is Roosevelt for having inflicted this horribly divisive situation on the Japanese Americans."

As a teenager, Takei remembers accusing his father of not fighting hard enough against internment, angrily declaring: "I would have demonstrated. I would have gotten all the good people to take a stand with us."

"My father tried to explain by saying he had three young children and a wife that he had to think about, and you have to think about the larger consequences. But when I finally accused him of leading us to slaughter, he said, 'Well, George, maybe you're right,' and he walked into the bedroom and closed the door."

"There are things in life," says Takei, "that you wish you could take back and you can't."

After peace broke out, Tule Lake was a secret shame.

"Our parents were so traumatized by the whole experience, they never really talked about it," says Barbara Takei, who found out about internment camps by reading a book, instead of from her mother, who was in Tule Lake.

But attitudes slowly changed, particularly after Congress apologized to internees in 1988 and authorized a token reparation of $20,000 to each internee. "We admit a wrong," President Reagan said as he signed the bill.

Before then, the issei, the older generation of internees, rarely attended the regular pilgrimages to Tule Lake, says Hiroshi Shimizu, a Tule Lake Committee member who was in the camp as a toddler.

In 1990 more than 100 isseis made the trip.

"Reparations made it possible for the community to begin talking openly about the conflict that had always been sitting within," says Satsuki Ina, a professor at California State University-Sacramento who made a documentary about internment, "Children of the Camps."

At the pilgrimages, held every two years -- the next one will be in 2002 -- internees tour what is left: the jail, a few other camp buildings where renters now live, a bit of fence here, the outline of a foundation there, a roadside plaque put up by state officials in 1979.

Since last October, Shimizu and about half a dozen others who have formed the Tule Lake Historic Preservation Committee have been trying to create a more tangible memorial.

A tentative plan would turn the area around the jail into a landscaped rest stop with perhaps a reconstructed barracks showing how internees lived.

Residents of the region have suggested that any exhibit should encompass the history of area World War II vets, including a nearby camp that held German prisoners of war.

Dust in the wind

For the old people who lived in Tule Lake, camp memories are hard to shake.Internees lived in wood-and-tarpaper barracks offering little protection. "The wind would come shooting up through the space in the floor," George Takei recalls.

Two years ago, Takei moved his 88-year-old mother, who has Alzheimer's, into his house and was puzzled when she kept complaining about dust. He'd run his finger over the furniture -- "See, Mama? No dust" -- but could not convince her.

"It got really irritating until one day it dawned on me: That's the way it was in camp, and she had reverted to the camp days."

Remembering Tule Lake, says Takei, who is chairman of the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, is "vitally important."

"There are a lot of dark chapters in American history, and some people don't like to address them. But it's very important that we know about the failures of American democracy to make it better," he says.

Click for online

calendars and events.