Sunday, August 5, 2001

Put to the test From a distance, a green swath of hillside can appear to be a perfect place for an outing. Yet upon closer inspection, the grassy knoll can turn out to be a tangle of brush and brambles grounded in mud. So it is with President Bush's education plan -- it's nice from afar, but far from nice.

Hawaii's educators fear President

Bush's education accountability

scheme will require too much

testing, too much time and

too much moneyBy Cynthia Oi

coi@starbulletin.comTo his credit, Bush has placed as his priority the improvement of education in America. During his first week in office, he proposed an ambitious blueprint to motivate educators across the country to find better ways to teach children.

At the foundation of his plan is a requirement that public schools test students in reading and math once a year in grades 3 through 8 and once in high school.

"Without yearly testing, we don't know who is falling behind and who needs help," Bush said, in announcing his proposals.

Educational administrators across the country are furrowing their brows over the testing proposal, including Paul LeMahieu, Hawaii's schools superintendent.

"I have no problem with testing, no," LeMahieu says.

His concern is the frequency. "How much testing is necessary to accomplish accountability goals?" Yearly, he says, "is a bit too much."

LeMahieu believes that only so much information can be gleaned from tests before the information becomes repetitive. "Before long, you will find nothing of value is added each year. The returns diminish," he says. "You lose the momentum by just assessing rather than teaching."

Without a doubt, testing brings with it issues of educational philosophies and the efficacy of tests. The president's program raises questions about the financial support the federal government will provide to give the tests and whether denying funds to failing schools will hurt more than help.

The tests would be used to identify the worst schools. Money would be provided, but if the schools do not improve, penalties would be instituted. Children could switch to other public schools and schools would have to change curriculum and staff. Students would be able to use taxpayer dollars for tutoring.

Although the U.S. House and Senate have yet to negotiate the details, testing is likely to remain in the legislation.

Not that there isn't value in testing. Here in Hawaii, LeMahieu had scheduled tests to set standards for assessment and accountability in public schools that were postponed until next spring because of the teachers' strike.

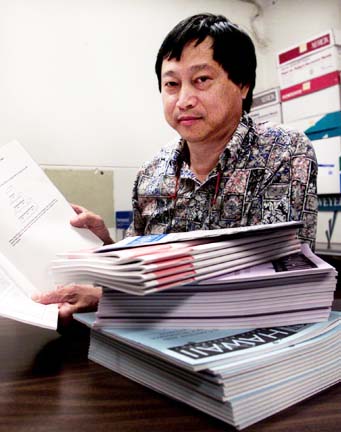

LeMahieu was frustrated as was Selvin Chin-Chance, administrator of the Department of Education's testing office. However, both see a silver lining. "It gave us more time to develop the test and develop practice tests to see how students respond to the structure," Chin-Chance says.

While many school administrators in other states may worry about instituting a new test, LeMahieu and Chin-Chance say Hawaii is in a better position than most.

"We have a statewide (school) system, so we have the structure to do these tests. Other states may have several systems or districts, so they would have to pull everything together," Chin-Chance says.

Having just developed a test, LeMahieu says, "We're in a good position to fit in. We can more easily slide into it."

Chin-Chance, who has been in his job for 20 years, is at once skeptical and optimistic about Bush's proposal.

"This can turn out to be a boondoggle or it can reach out for mighty change," he says. "The federal government can be like 'big brother' watching over your shoulder while the burden of testing will be on us. But I think it can help as long as the testing is not the only result. It can prove to be a lot of impetus to make our programs better."

He doesn't want to see a state-to-state comparison of scores, which he said would be unfair because Hawaii's students differ from others.

"Traditionally, Hawaii students haven't scored well in reading and language in nationwide kinds of tests," he says, because of racial and cultural differences, and immigrants for whom English is a second language. The tests he's developed are "more attuned to local and Pacific references" with place names and Hawaii-based literature.

The new tests were developed for students in grades 3, 5, 8 and 10 and Chin-Chance is somewhat concerned about having to create others. "But I'm not going to waste my time worrying about that. There will be time to adjust," he says, because annual testing is at least three years away.

The scoring process is another matter. Hawaii will have to contract with a test publishing company. There are only a half a dozen companies with the capability to handle such tests and if each state needs grading services, competition will be heavy. Because Hawaii's tests have questions for which written answers will be required, the process will be more time-consuming and more subjective.

Chin-Chance acknowledges that this will be a "tricky proposition," and Hawaii has little choice but to rely on their services. He says he can only be vigilant in back-checking.

Milton Kimura, a 7th-grade English teacher, is wary of big-scale testing. He and his colleagues at Jarrett Intermediate School have been testing to see how effective they have been in teaching language and writing. They have been testing with "prompts," topics that students readily respond to. In a practice test, students "did really well," he said, but when they were given a real test, the results were lower than expected. The teachers realized students were more successful on the practice exam because teachers were there to work with them.

"That's the kind of testing that helps the students. You offer comments, make corrections as they go," Kimura says. In that atmosphere, the final score wasn't the goal, he says. "It was the learning."

Effective testing "should measure the child at the beginning of the school year so that a teacher can see what the pluses and minuses are." Then teachers can work on the child's weak points so that by the end of the year, the student will have made gains.

Testing can set curriculum and standards for knowledge, but it cannot interfere with how a teacher does his job, Kimura says.

LeMahieu agrees. "Not every child learns in the same way. Curriculum enters a child's classroom through multiple pathways. Teachers are the ones who open the pathways. They are the ones who know each child best and they are the ones who can determine how best to give a child the opportunity to learn."

Testing can take away from teaching. "Tests cost a teacher in opportunity for instructional time. Tests take time. Preparing children for tests takes time," he says. "Could we be using the time better doing other things? I say yes."

Kimura and LeMahieu object to offering failing schools more money to improve, then yanking the funding if they don't. Kimura says: "If the school is in an area where parents can afford a tutor for after school, or if the students come from an area that is on the lower economic scale, there can be a difference in how well they do on tests. There are other factors besides a bad teacher that have an influence on children."

Carol Nafus, president of the 40,000-member Hawaii State Parent Teacher Student Association, thinks penalties aren't the answer. "If testing helps students and teachers are able to gain something out of how their students are doing, then it will be good.

"But a teacher shouldn't be held accountable for all students who have problems. Parents should be involved, too," she says.

Giving parents the option of switching children from a failing school to a better one won't work in Hawaii, she says, because there are only so many schools on each island. "On Lanai where I live, parents have no other options."

LeMahieu says he'll make the best of what the federal government requires. "One of the things that I do know is you don't pull away from people the very wherewithal they need to perform as a sanction for not having performed," he says.

Chin-Chance has a budget of $1.2 million to pay for testing and if it is to be required every year, he'll need a lot more than that. With a staff of just four people, "the sheer numbers of moving that much paper will be a challenge."

LeMahieu may have to hold him to that. The schools chief laughs heartily when asked if he expects that Bush and Congress will provide enough money for the testing program.

"What they say they'll pay will be half of the half of what they will actually pay," he says. "That's my formula."

He totes that up with the experience he's had with the federal government promising to pay "40 percent" of the cost of special education. "They've never paid more than 17 percent anywhere and never more than 8 to 12 percent in Hawaii."

Says teacher Kimura, "There's never enough money for education. Unless we stop making missiles, schools won't get what they need."