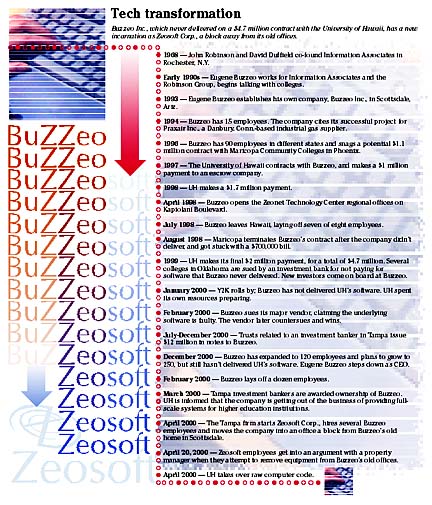

Chasing Buzzeo On a warm spring morning in a suburb of Phoenix, a former shipping industry executive had a locksmith open the offices of a failed software firm.

The University of Hawaii and

others are out millions, with little

hope of getting any money backBy Tim Ruel

truel@starbulletin.comVincent J. de Sostoa and other former employees of the company Buzzeo Inc. began removing computer equipment from the Scottsdale office and packing it into a truck, but were interrupted by the office manager. Buzzeo owed rent and had lost the lease. That's why the locks were changed. There was an argument.

A couple of the employees jumped into their truck and started to pull out of the parking lot. The manager got in his car and blocked the exit.

The cops came, and de Sostoa told police he was legally collecting what belonged to a new company that had taken over Buzzeo's assets through an Arizona court order.

Police charged de Sostoa with trespassing, but did not arrest him, nor did they take back the equipment, according to the police report.

What Buzzeo's former employees removed from those offices may be the only solid pieces left of a company that burned away tens of millions of dollars, several million of which came from Hawaii taxpayers.In 1997, the University of Hawaii awarded Buzzeo a $4.7 million contract to design the software for a new computer information system. Buzzeo went out of business a few months ago, never completing its order.

In late April, UH took over the project's basic program code, which still needs work. UH is not investing any more money to develop the code, but hasn't ruled it out as a future possibility, said UH spokesman James Manke. No lawsuits have been filed by UH. Industry experts said it could take millions more dollars for UH to develop a system.

"How many millions is really the question," said Paul Pagliarulo, director of administrative software services at Boston's Northeastern University, which suffered a year-long delay in rebuilding its computer systems when another Phoenix firm, indirectly related to Buzzeo, went way over budget and pulled out of its projects.

UH is one of many U.S. colleges that has run into expensive problems in the past few years after buying software from a slew of loosely related high-tech companies that did not live up to their contracts.

But the story of the failed Buzzeo Inc. is possibly the most colorful.

Across the nation, several private companies and public universities, and the state government of Oklahoma are trying to pick over what is left from the company. The No. 1 question on the minds of attorneys: Is it worth it? At first glance, there is nothing to go after. Buzzeo is closed, its assets gone.

But Buzzeo's key employees are back in business, operating under a new name -- Zeosoft Corp. -- in new offices, just a block away from their previous digs in Scottsdale, Ariz., with the equipment removed during the alleged trespassing incident.

Buzzeo Inc. isn't the only software manufacturer that has drawn fire from institutions of higher learning. Last year, Cleveland State University spent nearly $3.4 million on consulting firms to recover from a crisis that started after the university converted its systems to software sold by Pleasanton, Calif.-based industry giant PeopleSoft Inc. UH not alone in travails

with softwareBecause of problems in the system, scores of students waited months for their financial aid. Student transcripts contained errors. At fault was a combination of software glitches and data-entry mistakes by the university, according to officials quoted in the industry publication Chronicle of Higher Education. Between 1995 and 2000, Cleveland spent $11 million on its PeopleSoft systems. The original cost was estimated at $4.2 million. Similar problems arose with PeopleSoft at the San Francisco Unified school system, which bought $5 million worth of software in 1996. The software was supposed to be ready before the year 2000, but the project was plagued with bugs and school officials pondered scrapping the entire program. Instead, an independent board selected PeopleSoft to come in and fix the problems, at an additional charge.

PeopleSoft is giving the San Francisco schools a reduced rate for the work, said Lisa Sion, the company's public relations manager for education and government.

Colleges don't realize that there is more involved to a student information system than installing a new computer program, Sion said. The college tech-support staff members had to be retrained and administrative workflow changes.

"You're not just buying software," Sion said.

Another software company, USA Group TRG, abandoned contracts in 1996 with more than a dozen universities in different states after the company went over budget and found the project was too big.

In March 1997, the chairman of the nonprofit parent company USA Group resigned, just days after the Indiana company's board of directors learned of his January conviction for resisting arrest.

Buzzeo started as a small, privately held Arizona software firm in 1993, named after its founder, Eugene C. Buzzeo, a software executive who had worked for Dun & Bradstreet. Eugene Buzzeo entered discussions with his first two customers while working for another Phoenix consulting firm, the Robinson Group. Buzzeo soon left Robinson and started his own business.

Buzzeo Inc. planned to sell software to colleges that would enable students and administrators to manage class schedules, transcripts and financial aid through a site on the World Wide Web. With Buzzeo's computer code, a college could have a whole new system while keeping its old central machines, a major savings.

Buzzeo was not the only player in the business, but the firm was said to be at the forefront of the technology. Buzzeo began doing work for schools in several states, including a community college system in its own backyard in Phoenix. In 1994, Eugene Buzzeo told an Arizona newspaper the 15-employee firm would ultimately target Fortune 500 companies, as well as the thousands of institutions of higher education across the United States. Two years later, Buzzeo had 90 employees, offices in Scottsdale, Atlanta and Chicago and a lab in Boston.

In 1997, a UH committee unanimously picked Buzzeo to provide software to overhaul the university's badly outdated information systems on all 15 campuses and education centers statewide. The new software would provide services for admissions, class scheduling, transcript management and registration. At the time, the Y2K bug was expected to pose major problems, and Buzzeo was to be the solution. The UH committee had gotten in touch with other schools doing business with Buzzeo, and there were no apparent problems, UH officials said.

The firm was to open a technology center on Kapiolani Boulevard, and hire a couple dozen UH engineering students. Over a few objections about the risks involved, the UH Board of Regents approved Buzzeo's contract.

Only a year later Buzzeo ran into trouble. New investors told the firm to abandon its plans for a technology center in Hawaii, and so it did, laying off seven of its eight Hawaii employees. Several lawsuits were filed against the firm by its vendors on the mainland and by the owner of its former offices on Kapiolani. Other universities in different states backed out of their contracts, collectively losing millions of dollars without much software to show for it. Several colleges in Oklahoma were sued by a Beverly Hills, Calif.-based investment bank that had bought up Buzzeo's contracts, even though Buzzeo had not completed its projects.

Late last year, company founder Eugene Buzzeo, 45, stepped down as chief executive, although he still had stock in the company. Buzzeo has since started a new company, Hermitage Hi-Tech Ventures Inc., in the small town of Hermitage in western Pennsylvania. The company's main project is retail shopping Web site Catalogs-Galore.com. Buzzeo was on vacation last week and couldn't be reached for comment.

In late February, a dozen employees were laid off at Buzzeo Inc. A core group of about 20 workers stayed on board.

In March, customers and attorneys dealing with Buzzeo Inc. stopped hearing from the firm altogether.

The reason: Arizona Superior Court in Maricopa County had awarded Buzzeo and all its assets to the principals of First American Investment Banking Corp., of Tampa, Fla. The investors, Frank Musolino and Geoffrey Todd Hodges, had sat on Buzzeo's board of directors since 1999.Judge Gary Donahoe said his order in favor of the investors beat any other claim against Buzzeo. The new owners had sued a month earlier when Buzzeo defaulted on $12 million in notes. Buzzeo signed the notes with trusts linked to the Tampa investors between July and December 2000, court documents show.

On April 10 this year, the investors in Tampa registered a new private company, Zeosoft Corp., and hired Buzzeo's former chief financial officer, de Sostoa, and a core group of employees who had remained with Buzzeo until the end. Ten days later, de Sostoa had a locksmith open Buzzeo's offices to remove the computer equipment, resulting in the scuffle with the manager. The office of the Scottsdale prosecutor is reviewing the trespassing charges.

De Sostoa, 57, joined Buzzeo a year ago after leaving his post as senior vice president, treasurer and chief financial officer of Stamford, Conn.-based oil shipping company OMI Corp. He is now chief financial officer of Zeosoft Corp.

De Sostoa declined to comment, referring calls to Zeosoft's attorney in Tampa, Hodges, who also serves as general counsel for the First American Investment Banking Corp. Hodges did not respond to requests for comment.

Musolino, majority owner and director of First American Investment Banking Corp., is listed in Florida state records as the director of Zeosoft.

Zeosoft's new head office is a block down the street from Buzzeo's old location in Scottsdale, Ariz. The company has posted a Web site, www. Zeosoft.com, which says it has 30 employees. Zeosoft's new corporate logo is exactly the same as Buzzeo's old logo. One key difference between the companies: Zeosoft's primary software product is now geared toward the health care industry, not higher education.

The University of Hawaii was especially struck by the closing of Buzzeo. The only form of monetary relief the university was to get if the contract wasn't met was a small amount of stock in Buzzeo, which is now worthless. The university had no performance bond to guard against loss if the terms of the contract were not fulfilled.

UH used a third-party escrow company to pay Buzzeo the $4.7 million. After Buzzeo closed its offices in Hawaii and lost its contract with the community colleges in Phoenix, the Hawaii Legislature kept approving funds to pay the escrow company and paid the full amount by 1999, state records show.

Buzzeo still appeared to be making progress, said Eugene Imai, a UH administrator who presented Buzzeo's proposal to the Board of Regents in 1997.

Many U.S. companies that have attempted to provide information systems to educational institutions go back to one former company, Information Associates, which was founded in Rochester, N.Y., in 1968. Eugene Buzzeo, who later founded Buzzeo Inc., worked for the company in the late 1980s. The firm's co-founders, John G. Robinson and David A. Duffield, have since started more companies. Starting from the same point

Robinson founded the Robinson Group in Phoenix, which also employed Eugene Buzzeo in the early 1990s.

In the late 1980s, Duffield became chairman, president and chief executive of PeopleSoft. Information Associates is now the property of software provider Systems & Computer Technology Corp., based in Malvern, Pa.

In 1994, the Robinson Group was purchased by Indiana-based USA Group, which formed USA Group TRG. The company backed out of more than a dozen university contracts in 1996. USA Group downsized its information technology division in 1997 and was soon purchased. The company today is more commonly known as Sallie Mae, the student loan services giant.

Former Robinson Group principals emerged in 1997 as a small Phoenix company that was quickly snapped up by Baltimore-based Hunter Group and successfully completed several software consulting projects. The Hunter Group was bought earlier this year by London-based consulting company Cedar Group Plc.

"I call them all the bastard children of John Robinson," said Paul Pagliarulo, director of administration application services at Boston's Northeastern University.

When the contract was awarded, Hawaii government officials held press conferences to promote the deal. Gov. Ben Cayetano praised the company in his 1998 State of the State address. "I have hope when I hear that our new high-tech firms -- Square USA, Uniden and Buzzeo Inc. -- are hiring many of their new employees from the University of Hawaii's School of Engineering," Cayetano said.

Buzzeo was to hire up to 30 employees in Hawaii, with average salaries from $30,000 to $70,000, for an annual payroll of up to $1.5 million. The Zeonet Technology Center opened on Kapiolani in April 1998 with eight employees. The center was cut to one worker three months later at the request of Buzzeo's new investors, Eugene Buzzeo said at the time.

Later, UH officials said they knew the deal was risky, but they had no idea Buzzeo would dissolve. "Safeguards are only as good as the entity you're to go after," said Imai, senior vice president of administration at UH.

One UH Regent, John Hoag, vocally opposed the contract with Buzzeo. Hoag, a retired president of First Hawaiian Bank, said he was concerned about Buzzeo's financial viability.

"I think the problem, frankly, is that people who work for a university don't necessarily have the business acumen to study these issues, and tend to get sold on salesmanship rather than on hard figures," said Hoag, who later stepped down from the Board of Regents. "It seemed like a great idea."

"I think we always felt it was a long shot, even under the best of circumstances," said David Lassner, a UH official who led the committee that picked Buzzeo.

UH and the state government weren't the only ones in Hawaii left holding the bag from Buzzeo.

Bob Cunningham, who quit his own Internet firm to join Buzzeo shortly after the UH contract was awarded in 1997, is owed back wages from when the firm closed its Hawaii operations.

"By the time that we were laid off, we hadn't been paid for quite a few pay periods," Cunningham said. "So at that point, Buzzeo Inc. owed me over $10,000 in missed paychecks. Despite repeated promises from the company, I've never seen a penny of the back pay."

Unlike Buzzeo's other Hawaii employees, who eventually got their wages, Cunningham refused to sign an agreement to not sue the company. Cunningham now works for Honolulu information technology firm Commercial Data Systems Inc. But Buzzeo is probably not worth suing, he said.

In January 1999, Buzzeo stopped paying rent at 1601 Kapiolani Blvd., according to a lawsuit filed by the landlord. Buzzeo also stopped paying the contractor that renovated the offices. The contractor filed a lien against the landlord, Hong Kong movie mogul Sir Run Run Shaw, who built the office in 1992 on the site of the former Victoria Station restaurant.

In June 1999, Shaw's Kapiolani Properties Corp. sued Buzzeo and won nearly $300,000.

Winning a suit against Buzzeo, however, does not guarantee payment, as the Versant Corp. learned. The Fremont, Calif.-based database maker was one of Buzzeo's key suppliers, providing the underlying software for Buzzeo's products. Buzzeo stopped making payments and sued Versant in February 2000, saying there were technical problems with the software. Versant countersued and won. Buzzeo was supposed to pay Versant $700,000 plus interest but never did. Versant is examining other ways to recover the money, an attorney said.

Other cities and states have been coping with the fallout from Buzzeo.

Eugene Buzzeo began discussions with one of his first customers, the Maricopa Community Colleges in Phoenix, before he had left his former firm, the Robinson Group, which was working in the same business.

In 1996, the Maricopa system contracted Buzzeo Inc. to revamp its information systems by March 1997. "It looked like it was to be a wonderful thing," said Margaret McConnell, assistant general counsel for the Maricopa Community Colleges. The colleges paid $792,000.

But Buzzeo kept changing its methods, always trying to chase newer technologies, and kept pushing back deadlines. The contract was canceled in August 1998. The colleges never got a penny back and are now spending up to $2 million to build another system using other companies. Lawsuits were never filed.

The state of Oklahoma is learning the cost of a legal battle.

In 1999, Beverly Hills investment banking firm M.L. Stern & Co. sued three of Oklahoma's two-year colleges. M.L. Stern had bought Buzzeo's contracts with the colleges and sued to collect, even though Buzzeo hadn't delivered. More recently, M.L. Stern sued the public University of Science and Arts of Oklahoma in May.

An M.L. Stern attorney could not be reached for comment.

The field Buzzeo entered -- developing a full suite of software for universities -- was extremely risky, said Jim Lyon, a former senior vice president of Information Associates in the late 1980s, and boss to Eugene Buzzeo. College software a tough field

"It always takes more money than you think it's going to," Lyon said.

Some universities are more complicated organizations than even the biggest Fortune 500 companies, said John Curry, executive vice president at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

For years, universities had built their own systems, and the software code was buried in a programmer's head, not on paper, Curry said. Plus, university staff members are frequently paid through a combination of grants and university funds.

"Just that funneling effect is complex to most payroll and human resources systems," Curry said. "None of us understood how complicated our worlds were."

Universities have multiple departments with different demands. The complexity of meeting those demands increases when vendors attempt to design one piece of software loosely enough to suit more than one college.

"You will never see a problem-free implementation," said Paul Pagliarulo, director of administrative applications services for Northeastern University.

Across the nation, millions of dollars have been spent by universities on information systems that didn't work as planned. Is it an appropriate risk for institutions of higher learning?

"I think we'll look back on it and say it was," said Curry, of MIT. Once developed, the new student information systems could be around for the next 20 years, with vendors providing continual updates. At the same time, universities have also been forced to rewrite their business practices, becoming more efficient and eliminating paperwork. "In my view, much of the cost was the cost of revolution," Curry said.

The Oklahoma Attorney General's Office has filed a counter claim against the former Buzzeo Inc. on behalf of one of the colleges. A trial is set for January.

In 1999, Oklahoma City Community College sued Buzzeo, saying the college had paid for $500,000 in software that was never delivered. Buzzeo countersued, saying the college breached its contract by not paying Buzzeo the exact amount stated in its contract. The suits were dropped last year.

After the problems began for Buzzeo, the UH contract became something of a last stand. Other colleges licking their wounds were told last year to look to the UH deal as a sign that Buzzeo could make it. During the year 2000, the company expanded its presence in Scottsdale, taking up nearly the whole office complex, according to a former tenant.

In June 2000, Buzzeo was a co-sponsor for an annual software conference for Java, an advanced Internet computer language that Buzzeo was touted for supporting. The company also had opened a Buzzeo Learning Center training lab next door to its Scottsdale offices.

Buzzeo officials told the Greentree Gazette higher education business magazine in September that the company had 150 employees and planned to add another 100 by April of this year.

In January, Buzzeo began setting up the first computer program, a financial aid module, for testing at UH.

But that was it. In March, around the time Buzzeo was awarded to the officers of the Tampa investment firm, UH officials learned Buzzeo was leaving the business of providing full-scale systems for universities. UH officials have not decided whether to build the system on their own, contract the job out to vendors or do a combination of both. In late April, an escrow agent turned over the rest of the unfinished program code Buzzeo had developed for the student information system, in keeping with its contract with UH.

Buzzeo failed because it kept shifting directions to keep up with newer technologies and lost sight of its clients, said a former employee of the company, who did not want to be identified. The firm's ideas were solid and could have succeeded under better management, but instead, the company burned through millions of dollars and never delivered to its customers, said the former employee.

Hawaii Pacific University never went for Buzzeo. The private college would have had to hire staff to test the system, said Justin Itoh, associate vice president and chief information officer at HPU. Plus, Buzzeo had no history. "Our biggest shortcoming with it, was it wasn't established," he said. Instead, over the past few years, HPU has bought software from Campus Pipeline Inc., Systems & Computer Technology Corp. and WebCT.

One observer offered a more esoteric explanation for Buzzeo's demise.

In the office where Buzzeo once stood in the Scottsdale Airpark business center, a previous tenant had once offered a million-dollar prize drawing. The company reneged on the offer, then disappeared with the cash, according to Skip Niemiec, an architect who once worked in the building. Maybe it's the office, he surmised. "It's almost like it's got bad karma."