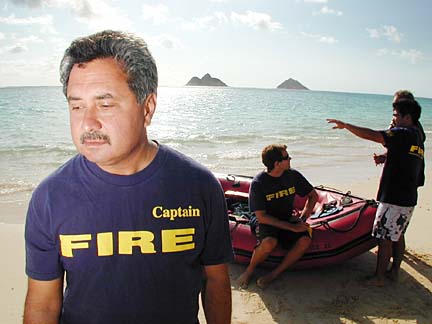

For Richard Soo, home is more than the three-bedroom duplex apartment that became his in January after six years of waiting for a Hawaiian homestead. Court case worries

homesteadersBy Jean Christensen

Associated PressIt's Kapahu Street itself that the Honolulu firefighter considers home. And he considers his neighbors -- fellow native Hawaiian homesteaders -- all part of his family.

"People are playing ukuleles. In garages, people are teaching hula. We can hear the kupunas (elders) talking about old times and speaking Hawaiian," Soo said. "It truly is a Hawaiian renaissance of sorts."

That block-by-block renaissance eluded Soo's father, who died 10 years ago while on the Hawaiian Home Lands waiting list. The program set up by Congress in 1921 and now administered by the state allows those with at least 50 percent native Hawaiian blood to receive 99-year land leases for $1.

Soo's homestead lease enabled him to buy the duplex for $185,000 -- about half what similar properties in urban Honolulu go for. He hopes to pass the lease on to his daughter, now 27, when he dies.

But a federal court lawsuit has him worried he won't be able to do that.

Patrick Barrett, a 30-year Hawaii resident, sees the Hawaiian Home Lands program and others that specifically benefit indigenous islanders as unconstitutional racial discrimination.

He wants the programs opened up to non-Hawaiians like himself -- a move many say would so dilute the programs' focus as to make them pointless, with devastating consequences for a group with some of the highest rates of poverty, disease and lack of access to good housing and education.

The vehicle for the challenge is a February 2000 U.S. Supreme Court ruling striking down a law that barred non-Hawaiians from voting in trustee elections for the state-run Office of Hawaiian Affairs. Barrett's attorneys say the ruling showed the high court's strong distaste for racial preferences.

Supporters of the programs, who include most elected leaders in Hawaii, say the decision applied only to voting in a state-run election. They argue the preferences are allowed because the federal government has accepted a trust obligation to native Hawaiians that is similar to its relationship with American Indians and Alaska natives.

A hearing before U.S. District Judge David Ezra is scheduled today on a motion by the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, one of the agencies named in the lawsuit, to dismiss the complaint on grounds that Barrett filed it before he applied for any programs funded by the agency.

Regardless of the hearing's outcome, both sides say legal challenges will continue, with the Supreme Court likely to be asked eventually to decide a question it called "difficult terrain" in last year's Rice vs. Cayetano decision: whether Congress may treat native Hawaiians as it does Indian tribes, and whether it may delegate that authority to the state of Hawaii.

"I think everybody sensed the ripples flowing from Rice were going to turn into a tidal wave," said Robert Klein, a former Hawaii Supreme Court justice who is representing the state Council of Hawaiian Homestead Associations.

"From the standpoint of the very humble set of people that are my clients, it's an area that they long ago thought had been settled, and they planned their lives and their futures around this commitment from the government," said Klein, who is part Hawaiian.

The lawsuit targets a state constitutional provision that provides for the Hawaiian Homes Commission, the Office of Hawaiian Affairs and native Hawaiians' gathering rights.

In the view of Barrett -- his attorney, Patrick Hanifin, said Barrett did not want to be interviewed -- those programs and rights treat native Hawaiians as a specific racial group, and preferences given to that group violate the equal-protection clause of the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

"A racial restriction is almost always unconstitutional," Hanifin said. "The government has to show a compelling state interest, and it has to be narrowly tailored, and we think that these programs ultimately flunk that test."

Hanifin questions the oft-stated motive for the programs of preserving a people whose kingdom was overthrown by an American-dominated cabal in 1893 and whose population was dramatically reduced after the first Western contact by Capt. James Cook in 1778.

The state's 200,000 residents who are at least part Hawaiian -- about 20 percent of the population -- have never been a tribe in the same sense as American Indians, he said.

"You're dealing with a group of people who are thoroughly integrated into the politics of Hawaii, the society of Hawaii, the economics of Hawaii," Hanifin said. "This is not a group that is sloughed off onto a reservation here."

Even the ukulele, a symbol of Hawaiian music, was an import from Portugal, he said.

"Why make that sharp distinction? Why draw artificial boundaries between fellow citizens?" Hanifin said.

But Klein said Congress has recognized -- and the vast majority of Hawaii residents agree -- that Hawaiians have a distinct culture and traditions that should be preserved with help from programs that offer education, health and housing assistance.

"There has been an intermixing of cultures as part of the Hawaiian spirit of aloha," Klein said. "That doesn't mean that because Hawaiians were welcoming they all of a sudden cease to exist."