Sunday, July 1, 2001

Ka Iwi he 300-odd coastal acres along Oahu's southeastern tip from Wawamalu Beach to Makapuu Point isn't the pristine wilderness that usually attracts the passionate defense of conservationists.

Will the plan to save the

last uncluttered stretch of

coastline on Oahu destroy

it in the end?By Cynthia Oi

coi@starbulletin.comThe human footprint has scarred its beauty with a black-tarred utility road, rusty hunks of metal, debris from construction projects and the ordinary litter of broken bottles, tattered clothing and fast-food wrappers.

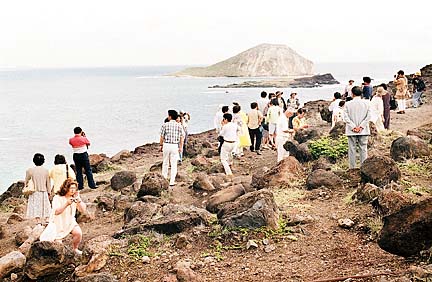

Its mangroves and estuaries, rough tidal pools and arid-scrub vegetation grate against the more familiar image of Hawaii with swaying palm trees, white sand beaches and green mountains.Yet this short stretch of shore has aroused people to battle long and hard to keep it free of hotels, houses and golf courses. As the last piece of Oahu's open accessible coastline, it has awakened a visceral need for natural landscape on a small island crowded, paved over and hemmed in by structures.

The preservation of this segment of Ka Iwi illuminates a dilemma across the country about how to leave natural resources as untouched as possible while opening them up for people to enjoy. It also tells a story about the desire of citizens and a government's willingness to listen, how people and power can work together toward a common end.

But there is a hitch. When the state and the land owner settled the price of the land at $12.85 million last month, most people assumed that unwanted development would not blemish this part of the coastline. However, with bureaucracy and regulation in the mix, what the state sees as benign improvement is in the eyes of others a scar across the landscape.

At the heart of the conflict is money. The land owners, at the time known as Bishop Estate, wanted $80 million for the land. A trial was to begin this year to set the price, but the estate, already in litigation on another piece of land, chose to negotiate instead. Political and public relations brought the final number to within reach of the state, which earlier had put up $11.6 million.

However, the state, knowing it would be unable to carry the financial load alone, allocated $4.9 million in federal scenic highway money to make the buy. With these funds came requirements. A good one is that utility lines will be buried underground to clean up the view. A bad one is that part of preserved landscape must now be paved for parking.

Ka Iwi defender David Matthews points to the irony of the situation. "All the energy put behind preserving the area in its natural state -- and now they're going to cover it in concrete."

Of 'bones' and beauty

Ka Iwi takes its name from the channel that parallels the 4.5 miles of coastline from Hanauma Bay to Makapuu Point and from the Hawaiian word iwi, or bones, that the rocky land mimics.As Kalanianaole Highway leaves behind the sprawling suburbia of Hawaii Kai and the crowded tourist haven of Hanauma, the road curves northeast to unveil Ka Iwi, first in high cliffs of raw, black-umber volcanic striations left by the most recent eruptions on the island. The coastline descends to Sandy Beach and the undeveloped strip of land across Kalanianaole that sparked an initiative to stop a housing project and eventually inspired the move to save all of Ka Iwi. A golf course and the rooftops of homes mauka hint of what would have been if not for the preservation efforts.

Makai lies the final sweep of Ka Iwi, from Kaloko and Kahoohaihai inlets and Kailiili Bay and Queen's Beach, through archaeological sites, endangered and other native plants and remnants of an ancient trail. At Makapuu Point, a lighthouse shares space with an overlook that has become a favorite vantage point when whales come calling in the winter.

On the highway, scores of cars are jammed along narrow shoulders. Other vehicles squeeze into the small lookout parking area, where sightseers step over cigarette butts and soda bottles to take in the view of Manana and Kaohikaipu islands. Cars whiz in and out of the traffic. Pedestrians scurry to cross the highway. Tourists, unaware of the crumbly nature of the promontory, edge up its ridges, hoping for a better perspective. It is obvious why safety is one of the state's primary concerns here.

Funding ties that bind

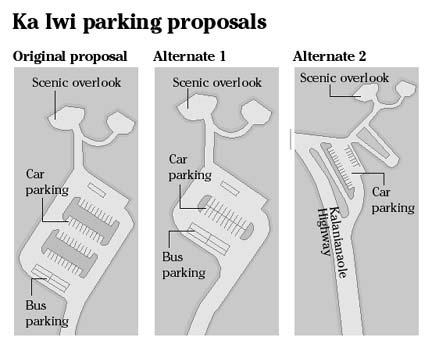

As assistant administrator of the parks division of the Department of Land and Natural Resources, Daniel Quinn is point man for the state's proposals for Ka Iwi. He took the brunt of criticism and opposition from two neighborhood boards when he recently presented plans that include two parking lots with a total of 80 spaces for cars and five for tour buses in the middle of the land.Quinn acknowledges that the parking areas will mar the view, but says the state must get the cars off the road. "If there's a safety problem we're aware of, we're obliged to make a change," Quinn said.

There's no arguing about requirements that come with federal funds. "The reality is that the state does not have enough money to buy the land, so when the opportunity to use the federal funding came up," the state took advantage of it, he said.

Compliance means parking lots, an improved road and an intersection with turn-off lanes, burial of overhead utility lines, access for disabled people and safe lookout areas. If the state doesn't fulfill these obligations, "the money is at risk," Quinn said. "If someone's got an extra five million bucks somewhere and wants to pay for the land, that would be a way to get out of this, but if not..."

State, citizens join forces

At 76 years old, David Matthews rejoiced when the state and landowner Kamehameha School (previously Bishop Estate) settled the dispute over the price of the land. An original member of the Ka Iwi Action Council, formed 14 years ago, he has been part of a campaign that began in 1988 when rumblings of hotels and golf courses spurred citizens to seek protection of the land, lobbying the Legislature to set it aside for a park.

The preservation atmosphere had been charged the year before when the City Council approved Bishop Estate's plans for housing across the highway from Sandy Beach. An initiative later overturned that decision but when the Council changed the zoning of the 30 acres from residential to conservation, the estate sued. Although a judge ruled earlier this year that the city must pay the estate as much as $200 million for lost revenues, the Sandy Beach price tag remains unsettled.

Hoping to avoid similar entanglements, the citizens' groups sought national park protection for the whole 1,600 acres of Ka Iwi shoreline, but that effort failed when the U.S. Park Service deemed the land unsuitable.

In the mid-1990s, the landowners and its lessees proposed to build homes, a golf course, a hotel and a commercial center on the Queen's Beach-Makapuu land.

City and state officials opposed the project and in 1997 the state began to make plans to acquire the land. In 1998, Gov. Ben Cayetano, using his executive powers, condemned the property, calling it "a necessary and important step to preserve and protect the open space and scenic vista."

The coalition and its preservation colleagues celebrated and cheered their government.

Diverging viewpoints

As the state was negotiating the price of the land, it started laying out its plans with the federal rules in mind. However, believing changes were a long way off, the citizens' groups seemed to pay scant attention to legal notices and announcements of the details.

Earlier this year, when the state took its blueprint to community meetings, people were surprised to see it contained foot bridges, bike paths and information booths. Their vision of a raw, natural landscape had disappeared beneath two parking lots that would sit "smack dab in the middle," as Matthews put it.

When David Washino of the East Honolulu Community Coalition moved here from California in 1989, he was captured by the beauty of the islands.

"If you aren't from here like me, you can appreciate the naturalness that's still left," Washino said.

Sparing what's left is what induced him to fight the city over its plan for an education center at Hanauma Bay. Although bloodied by an unsuccessful battle there, Washino is undaunted in his focus on Ka Iwi.

Standing along the highway, he points to the spots planned for pavement. "If you're going to put in a parking lot, don't put it where it's visible. Look at that how beautiful it is. Pave it for 40 cars and it's not beautiful anymore."He and Matthews believe that the parking lots will be the beginning of the end for Ka Iwi. Eighty cars equals 240 people, five tour buses equals 400 people, Matthews calculates. That number will multiply at least 10 times daily as people come and go.

"What happens when the parking lot gets full?" Washino said. "It gets crowded and the next thing is they put in more spaces."

Matthews predicts the state's actions will add Ka Iwi to the tour bus destinations that begin at Hanauma and end at Sea Life Park. He's not being selfish, he said, but the state should provide for visitors and residents who are interested in walking through a natural area instead of just driving through.

Fuming over buses

Others object to allowing tour bus stops. City Councilman John Henry Felix thinks buses and the number of people it brings will be "too intrusive."

"They create a lot of problems as far as safety is concerned and with so many people, it just adds to maintenance requirements with litter and so forth," Felix said.

Felix said the state should seek a balance that allows tourists and local people to enjoy Ka Iwi. He recalls how he used to go to Hanauma Bay as a boy, "but I don't go there anymore because it's become dominated by our visitors and that's a good thing and a bad thing. There has to be a compromise."

That's what the coalition's Adrienne King is hoping for.

"After all these years, this work, we just can't lose it now," she said. "We have to find a way."

The group made several suggestions to the state and its consultants, and alternate proposals have been drawn up to reduce and relocate one lot and either eliminate space for big buses or allow fewer numbers. Still, the federal and environmental regulations will have to be applied.

Matthews isn't as hopeful. "They should leave the thing alone. Why screw around what God made happen."

Deborah Ward, a hiker and an information officer with the land department, understands Matthews' point of view.

"We all grieve a little with every bit of nature that slips away," she said, but she doesn't see an insurmountable conflict brewing.

"If the community's voice is loud and strong, the state will listen," she said.

Said King, "It's all a matter of degrees. But I think the government wants to listen to us. It has before, or we wouldn't be here."