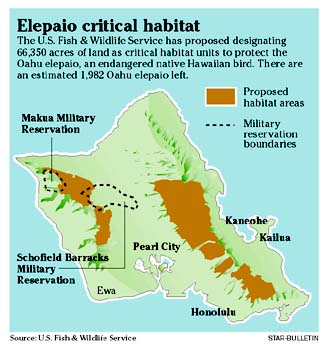

Government The federal government is moving to protect an endangered Hawaiian bird by designating more than 66,000 acres of land on Oahu as critical to the species' survival. The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service estimates that there are 1,982 Oahu elepaio left.

designates Oahu land

to protect bird

The wildlife service moves

to preserve the endangered elepaioBy Lisa Asato

Star-BulletinThe move is in response to a federal court order that the service publish a final "critical habitat" for the bird by Oct. 31.

The service says the remaining birds live in scattered locations which account for less than 4 percent of their original habitat. The five proposed areas cover 66,350 acres in both the Koolau and Waianae mountain ranges which would support approximately 10,100 birds, according to the service.

The term "critical habitat" refers to an area an endangered species needs to recover, and may require "special management or protection," according to the service. The idea is that the species would eventually recover enough to be taken off the endangered-species list. The Oahu elepaio, an insect-eating forest bird, was placed on the list last May.

State and private land comprise 95 percent of the proposed areas, but the greatest affect may be on land used by the military, said Eric VanderWerf, who was the primary author of the proposal."One of the main concerns is artillery training at Schofield (Barracks) -- and in the past in Makua Valley -- and that's whether the risk from fires associated with training will affect the habitat," he said.

VanderWerf, a fish and wildlife biologist, said that although the proposed areas are adjacent to training areas, there is still concern because of the potential for brush fires. "Just because of the proximity, there is still concern," he said.

Capt. Stacy Bathrick, spokeswoman for 25th Infantry Division (Light) and U.S. Army Hawaii, which trains in those areas, said she does not foresee an impact on training as the Oahu elepaio lives in and around areas already protected as "natural resource management."

Last year's listing of the elepaio as an endangered species "has not adversely affected training," she said, adding that "any future plans we will address and make adjustments accordingly."

Yesterday's proposal came as a result of a lawsuit filed last year by the Conservation Council for Hawaii asking the government to finalize actions to protect the species.

David Henkin, attorney for Earthjustice Legal Defense Fund, which filed the suit on behalf of the council, said some have raised concerns that the critical-habitat designation "somehow creates a nature preserve, and all of a sudden (those areas) are designated like a national park. That's not true."

"Critical habitat only comes into play when there's a federal connection," he said. He said state, county and privately owned parcels would only be affected if the owner wanted to undertake a project that is federally funded, for instance.

"If I'm not a federal agency and my property has been designated critical habitat ... it doesn't affect me at all," he said. "Anything you could have done before the designation you can do after because it just doesn't apply to you."

Paul Conry of the state Forestry and Wildlife Division said simply designating an area as essential does not go far enough in protecting the species. He said the state places a higher priority on getting funds needed to decrease threats such as rat predation and disease.

"The critical-habitat designation identifies areas that need to be protected for the future recovery," said Conry, wildlife program manager. "It is not guaranteeing there's going to be any funding for management in the future."