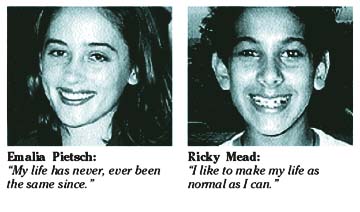

Dealing Emalia Pietsch, 16, of Honolulu, and Ricky Mead, 13, of Kailua-Kona have learned to cope with blood sugar tests, insulin shots, regulated diets and exercise.

with diabetes

Teens who learned to cope

Disease affects 95,000 here

will represent the isles at a

diabetes children's congress

By Helen Altonn

Star-BulletinBut they are hoping for a cure for diabetes so they can be like others their ages.

They will represent Hawaii in the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation International Children's Congress 2001, June 24-27 in Washington, D.C.

More than 200 children with Type 1 diabetes from all states, the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico will participate in the event to raise national awareness about the disease.

Children with diabetes do not outgrow it.

Delegates at the Children's Congress will go to Capitol Hill to remind Congress and the administration of the critical need to find a cure for the costly disease.Emalia and Ricky described the hardships of Type 1, or juvenile, diabetes in applying for the congress.

A Punahou School sophomore, Emalia was diagnosed on her birthday, Oct. 29, 1998.

"I was blown away by the news from my doctor, and my life has never, ever been the same since," she wrote.

She had lost a lot of weight and was down to 89 pounds. Her family and friends thought she was anorexic, she said.

Ann Pietsch, her mother, said she thought her daughter's weight loss was due to five-day workouts for the school volleyball team.

Emalia also was always thirsty and craving water. She would drink four glasses of water before bedtime, her mother said. "I thought this was kind of strange," Ann Pietsch said. "I don't care how good water is for you."

After the diabetes showed up in a urine test in her annual physical, Emalia was in Kapiolani Medical Center for Women and Children for four days to learn about the disease and how insulin works.

People said she was lucky because she was healthy and the disease was detected early, Ann Pietsch said.

But it has changed her life, Emalia said. Her diet has altered, with only "healthy food" in her house, she said.

"It is hard to go to the snack bar at school and watch my friends eat ice cream or other snacks when I know I can't have anything. The hardest thing of all is the temptations that come with every meal."

She also has to exercise, but that is not difficult since she plays volleyball and water polo, she said. The hardest part is learning how to regulate her blood sugar with insulin and give herself injections, she said.

She said it bothers her when people stare because of a huge bruise on her leg after accidentally hitting a blood vessel when giving herself a shot.

It is also "very embarrassing to be at a school function or at the movies and you have to bring out your needle to inject yourself," she said. "Everyone stares and thinks that you are 'shooting up' like a drug addict."

Ricky Mead, diagnosed with diabetes when he was 2, said it has been difficult growing up in Kona because he is the only one in his school with the disease and has no opportunity to meet other diabetics.

His mother, Debbie Lebo, a single parent of three children, "has spent sleepless nights taking care of me and making sure that I am healthy and have the best doctors to take care of me," he said.

They have to go to Oahu to see an endocrinologist because there are none in Kona, he said.

He said he tries "to make the best of my life" by surfing and playing sports. "I like to make my life as normal as I can. It is hard to do this because I have to be constantly monitored by my family and adults around me."

"You want them to live the most normal life possible," said Ann Pietsch, noting her relationship with Emalia was strained because she must be "mother, nurse, doctor, dietitian. She just gets tired of my preaching."

She said her daughter "knows all the do's and don'ts" and manages herself, but she could be in better control. "The hardest thing is portions. You can't eat pizza at 11 at night."

Emalia takes two insulin shots a day. She remains active -- jogging, paddling and playing volleyball and water polo. She has had a lot of support from her friends, who wanted to learn about diabetes, her mother said. "Life kept going on for her. She went to a sleepover only two weeks into diabetes."

Emalia's two sisters were tested for the disease but do not have it.

Ann Pietsch said she and her husband, Jim, do not know where it came from. She tells her daughter: "I don't know why this happened, but for some reason you were picked. ... Someday you'll find out."

Debbie Lebo has dealt with ignorance of diabetes, lack of support and medical specialists in Kona since Ricky was rushed to the emergency room with flu symptoms at age 2. He was in intensive care for two days and five more in the hospital.

"I had to become an expert and test blood sugars and give shots in order to bring my baby home," she said. She educated herself about the disease and flies Ricky to Honolulu for appointments with an endocrinologist every six months.

She said she has been networking through her computer the past 1 1/2 years for support. "Before that I was pretty much on my own. It's just hard; every day is tedious. It (diabetes) is life-threatening."

Ricky skateboards and plays hockey, so he gets a lot of exercise. But his diet must be controlled, and he cannot go to sleepovers because a lot of parents do not know about diabetes, his mother said.

"His blood sugar has to be checked six to seven times a day," she said, and he takes two or three insulin shots. His sugar level fell so low one night recently, she gave him orange juice and ice cream to raise it, then put him in bed with her to check him every hour.

"He's really been an angel about this," she said. "I know other kids have a hard time and don't want to comply."

However, he did have a rebellious streak a year ago, eating things in school that he should not, she said.

"My heart just breaks every time I hear about another child being diagnosed. I really think the answer is funding. I know there's a cure out there."

Education also is important, she said, because many people do not understand the disease. "A lot of people think their child will get it if they play with Ricky."

She has tried to talk to all of his teachers and coaches and other parents about diabetes.

"As a parent, you never stop worrying," she said.

There are two types of diabetes. Diabetes hits

95,000 in HawaiiType 1, known as juvenile diabetes, is a chronic, debilitating disease that occurs when a person's pancreas stops producing insulin.

It is usually, but not always, diagnosed in children.

Type 2 diabetes is usually diagnosed in adults whose bodies produce insulin but do not use it effectively.

Type 2 often can be controlled with diet and exercise.

Those with Type 1 diabetes must prick their fingers for blood to test their blood sugar and take multiple insulin injections daily.

About 95,000 Hawaii residents knowingly or unknowingly have the disease. Some 16 million Americans have it, with more than 5.4 million going undiagnosed.

Warning signs of Type 1 diabetes include extreme thirst, frequent urination, drowsiness, lethargy, sugar in urine, sudden changes in vision, an increase in appetite, sudden weight loss, fruity or sweet odor on breath, heavy, labored breathing, stupor or unconsciousness.

Complications can include blindness, heart attack, kidney failure, stroke, nerve damage and amputations.

For more information, call the Hawaii Chapter of the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation International, 988-1000, or toll-free from the neighbor islands, 888-533-9255.