Life at the bottom It is an alien environment with seasons of constant light and constant darkness, where temperatures plunge with wind-chill to 140 degrees below zero Fahrenheit, where residents depend on flights during a brief summer and are isolated during a long winter.

of the world

A former Hawaii telescope

operator enjoys the stark

beauty of Antarctica'South Pole Charlie at

home on the far frontiers

of scienceBy Helen Altonn

Star-BulletinThat glimpse of life at the bottom of the earth in Antarctica comes from Charles Kaminski -- "South Pole Charlie" to those following his adventures on his home page.

Despite the hardships, he gave up a 21-year career as research associate and telescope operator at NASA's Infrared Telescope Facility on Mauna Kea to run telescopes at the South Pole.

He was there in 1998-99 on sabbatical leave from the IRTF, operated by the University of Hawaii. After returning to Mauna Kea, he got a call asking if he wanted to spend another winter at the South Pole.

Although it meant "a life change," Kaminski, 46, said the decision was pretty easy because he likes exotic places. "I always wanted to be an astronaut, and the isolation at the South Pole was similar to a space mission."

In e-mail "chapters" and correspondence, he describes a close winter community of "Polies" doing pioneering science, facing dangers and keeping busy with research, housekeeping duties and social activities, such as costumed Mardi Gras parties and holiday dinners with white tablecloths and wine stewards.

"Creature comforts abound these days, compared to the early polar explorers," Kaminski said.

The station always opens around the end of October, a month after the sun has risen. It is "frantically busy" during the brief summer season with more than 200 people in and out, planes landing, cargo being handled, repairs made and construction being done, he described.Those activities quickly die when the station closes as it did on Feb. 18 this year -- leaving 50 "winterovers" (people who stay there during the winter) to keep things going for 8 1/2 months, he said.

It was "almost downright balmy" in mid-February at minus 35 degrees Fahrenheit, Kaminski said.

By March 25 the sun had set, and a month of twilight had begun with poor visibility and temperatures falling to minus 70 degrees Fahrenheit, or minus 140 degrees Fahrenheit with the wind-chill factor.

"I really enjoy the lifestyle here and the friendships that come about," he wrote to the Star-Bulletin. "We are in a special place, and the people are special ... the largest collection of overqualified people on the planet. We are 50 strong, the same as last winter, still the largest group to ever winter."

National attention was focused on the South Pole recently when a small plane made a risky landing there -- the first ever in winter -- to pick up Dr. Ronald S. Shemenski, suffering from gallstones.

Shemenski was feeling better, Kaminski wrote before the plane arrived, "but the wheels have started rolling, and it's a huge steamroller that is not now about to be stopped."

"We are preparing the skiway using D-6 Caterpillars in minus 84 degree Fahrenheit temperatures, for the first time dragging the snow to flatten it," he described. "The machines are running almost 24 hours a day. ...

"The auroras are many and beautiful lately, and those guys dragging the skiway have been getting front-row seats. Many oohs and aahs on the radio. It's been around minus 84 degrees F. for a couple of days now. Not much light left."

Shemenski was safely evacuated April 26, although he was "against all this hoopla" and people taking risks for his sake, Kaminski said.

"After two weeks of sleepless nights preparing for the event and surviving a full day of no sleep during it, the Otter mission was a success," he wrote on April 29. "We did the impossible, and along with it, we changed the South Pole forever."

The plane dropped off Dr. Betty Carlisle, who wintered at the pole in 1992 and 1995, "and since she has more 'ice time' than almost anyone else here, she has fit right in immediately," Kaminski said. "She put some salt in her pockets because she heard we needed some."

Shemenski is the second doctor Kaminski has seen rescued from the South Pole. Dr. Jerri Nielsen was stranded there for months with breast cancer before she could be rescued in October 1999. She diagnosed and treated herself.

Kaminski left Hawaii Oct. 31 for New Zealand -- starting point for people heading to the South Pole and much of Antarctica.

He was in Christchurch for a week waiting for weather to clear at McMurdo station on Ross Island, the U.S. staging area for most Antarctic trips.

Only eight were on the flight to the Pole, "but lots and lots of cargo," he said. He was able to sit in one of the jump seats in the cockpit. "Being a pilot, I ate it up and really enjoyed the views of the Transantarctic Mountains and glaciers as we passed them."

Kaminski runs a ground school for people at the station on Tuesday nights to learn about airplanes, along with the science-fiction movie night.

After a year away, he noted some changes at the South Pole, such as massive construction under way to build a new station.

There are several areas or sectors at the pole, depending on the function. The telescopes are in the Dark Sector, an eight-minute walk from the dome and living quarters. No lights or radios are allowed there in the winter.

The dome, about 150 feet across and 50 feet high, contains several buildings, including dorms, galley, computer room, library, lounges, storerooms, post office/store, weight room and gym. "Think small," he said.

Unlike the summer people who stay for only a few days or weeks, the winterovers spend an entire year there, so they are trained to be the station's fire and trauma team, he said.

"The Fire Brigade has a drill at least once a month, and with all the false alarms from blowing snow and faulty detectors, we keep busy."

"Winterizing" duties include closing up and shutting down things, removing all the electronics, reducing snow drifts and putting up flag lines for when it gets dark.

A tradition after closing is to watch the movie "The Thing," he said. They watched old and new versions and agreed the older one with James Arness is better.

Life at the South Pole is mundane at times, "and the realization that we are here at the bottom of the world can be quite sobering," Kaminski said. "We are isolated, but with the e-mail and Web connections we have today, it doesn't seem so far away. And really, we don't miss the commercials or traffic, and bill collectors discover we are hard to find."

Science has long been done at the South Pole, but it is much more aggressive now, says astronomer Charles Kaminski. At home on the far

On his Web site, Big Isle resident

frontiers of science

Charles "South Pole Charlie" Kaminski

chronicles life among scientists at the

bottom of the world. The site includes

his journal and dozens of photos.By Helen Altonn

Star-Bulletin"We are studying nothing less than the origins of the universe."

During his first South Pole stay in 1998-99, Kaminski operated an infrared telescope called SPIREX for the National Science Foundation, the Center for Astronomical Research in Antarctica and the University of Chicago/Yerkes Observatory.

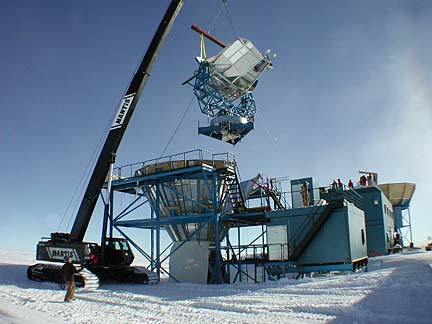

He left the pole toward the end of November 1999, when SPIREX was removed to make way for a new instrument called DASI (pronounced "daisy" and meaning "Degree Angular Scale Interferometer").

The DASI and Viper telescopes are major projects in what is called the Dark Sector of the station. DASI is made up of 13 individual small receivers that look at the same patch of sky and add things up interferometrically, Kaminski said.

SOUTH POLE CHARLIE

His Web address is

http://members.nbci.com/cdkaminski

Viper is a submillimeter telescope with a new instrument called ACBAR that looks at extremely distant galaxy clusters against background radiation of the big bang.

A lot of science at the South Pole involves the atmosphere because it is pristine, Kaminski said. "There is nothing upwind of here for hundreds, if not thousands of miles."

Air samples are constantly taken and studied for CO2 and other gasses to track long-term changes, he said.

Solar radiation changes reaching the earth, such as ultraviolet light due to the thinning ozone layer, are studied, and aurora and cosmic-ray investigations have been going on since the pole first opened in 1956-57 during International Geophysical Year.Weather also plays a big part in observations, Kaminski said. "Temperatures and wind speeds, along with small balloon launches, help fill in data for us."

A seismograph also is monitored for earthquake activity as part of a global network.