CARE seeks to Five agencies have formed a partnership to improve services to abused and neglected children placed in foster care.

rescue kids at risk

A joint effort aims to

improve medical services

and speed recognition of abuse

By Helen Altonn

Star-BulletinThe state has about 1,900 foster care children, said Susan Chandler, state Department of Human Services director.

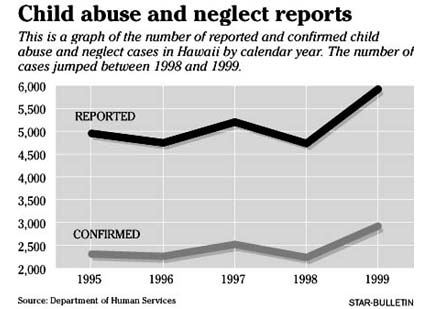

"We're getting more out but more are coming in," she said, noting confirmed reports of child maltreatment rose to 2,881 in the 1999-2000 fiscal year, from 2,537 during the period between July 1, 1998, to June 30, 1999.

"What we all want to improve, and this is a national concern, is to assure children in foster care are getting good comprehensive examinations and services," Chandler said.

Most foster care children have access to services through the state's QUEST health care program, she said. "We want to make sure they get it, that they actually go."

Collaborating in the effort to improve medical services for foster kids are the Kapiolani Medical Center for Women & Children; the Department of Human Services; the Department of Pediatrics, John A. Burns School of Medicine; the city prosecutor's office; and the Honolulu Police Department.Dr. Victoria Schneider, pediatrician and medical director of the Child Protection Center at Kapiolani, conceived the program "because of such a lack of medical services" for abused and neglected children. The Consuelo Foundation funded a group to visit two California centers with medical and child protection programs.

The overall program formed by the Hawaii partnership is called CARE, meaning Child at Risk Evaluation.

Within it is a pilot demonstration project called HOPE, or Hawaii Outreach Pre-placement Evaluation, located in the Child Protective Service's Ewa Beach facility. It is funded by a $176,000 Lange Foundation grant.

Schneider said CARE will provide an umbrella for services to children identified as abused and neglected or who are being investigated for maltreatment.

Injuries from abuse may include burns, poisonings, closed head and abdominal trauma, skeletal fractures and other injuries, she said, pointing out they may be life-threatening and some may be difficult to recognize.

CARE is focused on children who have injuries or who are being investigated by CPS or seen by a doctor for a pattern of bruising, she said.

Amy Tsark, Child Welfare Services Branch administrator, said: "Right now, when a child enters the system, we don't always know if the child has been abused. We often don't even know if the child has a medical condition or anything about their medical history."

Schneider said the CARE program can help in making a medical diagnosis of injuries or provide a doctor with a second opinion. It also will be a resource for police investigations, she said.

Medical attention particularly is needed to evaluate injuries and children suspected of being abused, she said.

Police, doctors or CPS workers could take a child to Kapiolani's emergency room for consultation with someone trained in child abuse, she said.

Improved accuracy in diagnosing injuries also can prevent mislabeling of cases as child abuse where a child may have a medical condition causing bruises, she said.

Where abuse is suspected, it is important to evaluate and document injuries properly so a child can be protected, she said.

Schneider said foster care children have a much higher rate of medical, developmental and mental health problems, so they need a pre-placement medical exam when they enter the system.

The purpose of that exam is to look for medical problems that may need to be treated, such as an ear infection or head lice, and to look for signs of abuse and neglect, she said.

Within 45 days of placement in foster care, a child is supposed to have a comprehensive health evaluation, Schneider said.

She said that will involve collecting all health information known on a child, doing a thorough medical exam, screening for developmental and mental problems, making necessary referrals, giving immunizations and making sure the child has a doctor who will have all the records and follow the child.

Looking at CARE as a big pie, she said, the first slice that has been funded is the HOPE program. It will enable Kapiolani to place a trained pediatric resident at the CPS unit at Ewa Beach on a weekly basis to do pre-placement exams.

Catherine Hong, a third-year pediatric resident, will be the first HOPE physician at the Ewa center. Pediatric residents will rotate there every eight weeks.

"This is a completely new area in pediatric training," Hong said. "Our job will be to learn to recognize patterns of nonaccidental injuries to the child."

Pediatric residents will be at the center once a week in the first year of the grant and twice a week in the second year.

CPS caseworkers will take a child to the center for a complete physical exam before foster home placement.

"It's very convenient for our workers up and down the Leeward side," Chandler said, explaining that currently they have to find a pediatrician available, or they take children to Kapiolani or to emergency rooms. Chandler said she would like to see the HOPE program grow, "then we could have an easier way for children in a friendlier environment to get their medical exams."

Kapiolani has equipped the Ewa center with a digital camera and computer equipment connected with a secure, encrypted link to the hospital.

If abuse is suspected, the resident pediatrician will send photographs of the injuries and consult with the hospital's forensic pediatrician while the child is still at the center.

Photographs will become part of the child's medical record, making subsequent investigation and prosecution for abuse more effective.

"We believe HOPE will provide us with higher levels of forensic evidence that can more accurately determine whether an injury is intentional," said Lt. Evan Ching of the Criminal Investigation Division. "Our hope is that we'll be able to intervene more quickly and effectively on behalf of the child."

CPS cases have increased significantly in the past decade, and abuse has emerged as a field of expertise within pediatrics, Schneider said.

More than 18,000 articles have appeared in medical literature involving child abuse, with 5,000 in the last three years, she said.

Medical information and medical ability to assess children with injuries have improved, she said. Yet, she added, funding to provide medical services has declined in Hawaii in the past decade.

"What we are currently able to provide (at Kapiolani Medical Center) nowhere matches the need."